- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shenandoah

About this book

From a distance, Shenandoah may look like any other small town, quaint and unassuming, and yet in one square mile, there are more treasures than the "black diamonds" of coal that run in her veins. Discovery of the Mammoth Vein of anthracite in the 1860s brought tens of thousands of immigrants to work the local mines; in turn, they brought their cultures and dreams of a better life in America. Within a generation, rapidly increasing population created the "Most Congested Square Mile in the United States." Later, a shift from coal mine to Main Street fashioned recognition for retail fineries, along with distinction as the "City of Churches." At the center of the Molly Maguire troubles of the 1870s and the 1902 coal strike that changed the power of the presidency, Shenandoah has long been recognized for defiance and determination. Mining disasters, financial adversity, and ruinous fires scarred memories of decades of prominence; however, Shenandoah's spirit has endured through the last 150 years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shenandoah by Anne Chaikowsky La Voie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

COAL MINERS

AND COLLIERIES

AND COLLIERIES

God Bless all the miners and their families now and forever.

—Shenandoah Miners Memorial

Demand for coal created Shenandoah. In the 19th century, this black, combustible rock was essential. Anthracite, or “hard,” coal burns “hotter” with less smoke than bituminous coal and was the primary fuel for industrialization, providing heat and power and endowing fortunes for those who controlled it. Since the discovery of coal in this area coincided with the Civil War in the 1860s, land speculators secured investments in Shenandoah and then profited instantly by selling this needed fuel to the Union army and factories of the North.

Since Shenandoah lies on the largest vein of anthracite in the world, coal became the blessing and curse of her people. Mines provided work and established the community, but prosperity was not found for the men who worked there. Perhaps most telling are the streets (Bower, White, Jardin, and Lloyd) named for the first owners of land tracts, “men who never saw Shenandoah nor ever visited their properties, since their investment was purely speculative,” according to The Path of Progress.

From the time of the Civil War, money was made by owning the land, the collieries, and the men who mined coal. Statistics for 1870s Schuylkill County list 22,000 coal miners, 5,500 of whom were “breaker boys,” who began from the age of six working 12 hours a day, six days a week, separating slate from coal. Numbers alone cannot describe the brutal conditions, where the expectation was death by accident or “black lung” (pulmonary disease caused by inhaling coal dust). Every year, hundreds were seriously injured or killed because even primitive safety precautions were ignored; secured timbering in shafts, ventilation, and water pumps were rare. Low wages had to be paid back to coal companies for inferior housing and costly food from company stores. Protests were dealt with by the Coal and Iron Police, who were known for their violent cruelty. Upon this foundation, Shenandoah was built.

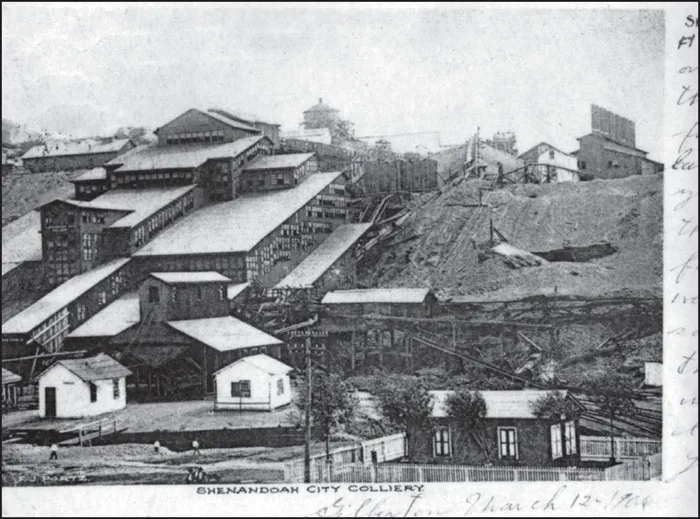

Before there was a Shenandoah, the first ton of coal was mined in the area by the Shenandoah City Colliery. The collieries, or complete mining operations, included all buildings aboveground that were used to process coal, along with the mine below. After Shenandoah City came Kehley Run, Plank Ridge, West Shenandoah City, Kohinoor, Turkey Run, Indian Ridge, Cambridge, William Penn, Maple Hill, Packers, and Locust Mountain. (JC)

Shenandoah City Colliery began operation in 1862; within the first year, it had built this shaft, the breaker and buildings, 47 tenant houses, and a large boardinghouse, all of which were located in the southern part of the borough. As soon as the railroad line was completed in 1863, the first shipment of coal traveled out of the area on the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. (SC)

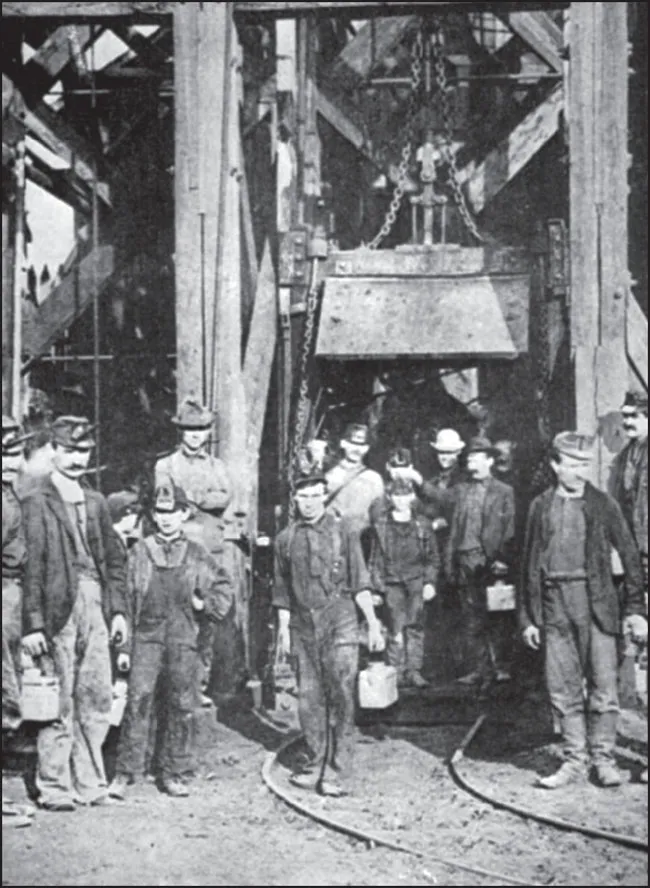

Start by looking at their hats. Less than protective, they served as a covering on which to attach oil wick lamps. Then observe their tools: a saw, a pick, and a lamp. Known as “growlers,” those metal pails held their mid-shift meal. Now scan their faces. Long hours, physically punishing work, hazardous conditions with negligible safety precautions, and insufficient pay were part of a miner’s struggle. (JC)

Although some boys were able to get an education and not work in the mines until they graduated eighth grade, many mine owners disregarded the 1885 labor act and hired boys as young as nine, as this 1910 photograph indicates. It was in these breakers that coal was crushed and separated into different sizes. Breaker boys would sit on narrow boards above troughs of quickly moving coal and pick slate and rock from the coal. (GSAHS)

Although some mules were born in the mines and never went to the surface, it was said colliery owners treated these animals better than miners. Mules, like the ones seen here in the Maple Hill Colliery stable, were used to haul coal out of the mines. Strict rules were used to protect the animals; miners could lose their jobs for not adhering to the guidelines. (SC)

An ever-increasing need for miners’ housing caused substantial changes to the town. Single men lived in boardinghouses; married men lived with their families in row homes or company houses. Some mines employed 800 men per shift, plus breaker boys. In 1870, a total of 132 collieries were in operation in Schuylkill County. Shenandoah alone shipped 537,790 tons of coal. Within two years, all 12 collieries in town were running, processing over one million tons. (DSI)

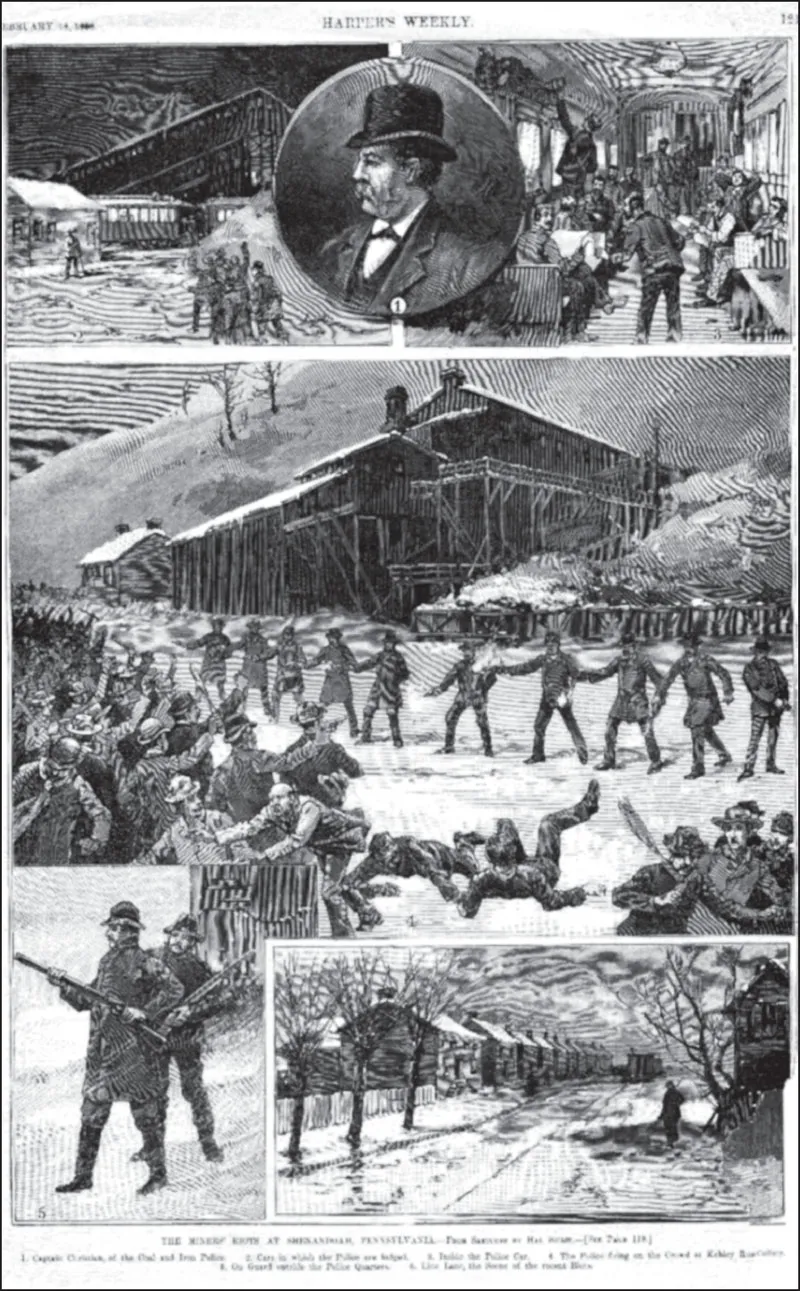

Harper’s Weekly magazine reported on riots in Shenandoah by using a series of drawings in the February 1888 issue entitled “The Miners Riots and Shenandoah Pennsylvania.” The scene in the center illustrates a confrontation at Kehley Run Colliery. For years there had been conflict between the miners and mine owners, most notably over access to union representation, shorter hours, and higher wages. (GSAHS)

A number of coal strikes had already taken place in the county by 1900. When miners asked for a wage increase, grievance procedure, and recognition of the union United Mine Workers of America, the owners refused to meet or to arbitrate. The union struck in the autumn of 1900, and the National Guard was called to keep peace. This photograph is of the Red Cross encampment in Shenandoah. (SC)

Not yet 30 years old when he became president of the UMWA, John Mitchell had already spent years working the mines as a mule driver and miner. When he organized the anthracite miners of eastern Pennsylvania, not only did he meet with organized employer resistance, but also pessimism and despair on the part of the miners. It is reported that he wept when he saw the plight of the Shenandoah miners. (SC)

Troops of the Pennsylvania National Guard were sent to Shenandoah to maintain order during the 1900 strike. John Mitchell, president of the UMWA, attempted to negotiate with coal operators; the operators refused to recognize the union. Mitchell called for a strike of the anthracite coal miners. Despite the fact that only 9,000 mineworkers in the Coal Region were UMWA members, over 110,000 mine workers (of 145,000) joined the strike within the first week. (JC)

In May 1902, one hundred fifty thousand mineworkers struck for shorter hours, union recognition, and other demands. On July 30 in Shenandoah, 5,000 strikers and police engaged in a riot resulting in injury and death. The Pennsylvania National Guard then occupied the town, and the strike continued for another th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Coal Miners and Collieries

- 2. From the Old Country

- 3. City of Churches

- 4. Main and Centre Streets

- 5. Saturday in Shenandoah

- 6. Champions

- 7. Shenandoah Spirit

- 8. Adversity and Disaster

- 9. In Honor