- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

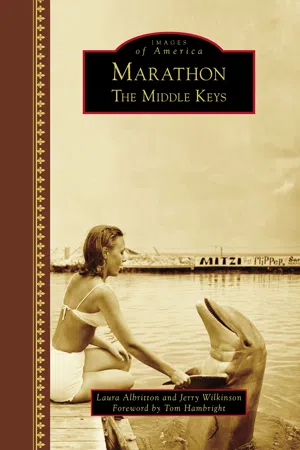

About this book

The Middle Keys have experienced a fascinating history, from the time when wreckers plied the Florida Reef to the days of Henry Flagler's audacious overseas railroad.

Once the Overseas Highway opened, travelers could reach Marathon by car and tourism boomed. As more people settled in Marathon, the community grew and flourished. The majesty of the Middle Keys' two Seven Mile Bridges has inspired postcards, paintings, and even movie scenes. Local institutions like the Dolphin Research Center and the Turtle Hospital have also garnered a host of fans. Images of America: Marathon: The Middle Keys captures the story of these unique islands and their rich photographic legacy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marathon by Laura Albritton,Jerry Wilkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

CAYOS DE VACAS

TO KEY VACAS

TO KEY VACAS

Explorers sailed past the Middle Keys from the days of Juan Ponce de León, when Spain laid claim to Florida’s cayos, or keys. Whites did not settle here until the 1820s, when salvaging shipwrecks on the reef became hugely profitable. By then, the United States had taken possession of the Florida Keys and would in time bring elections, laws, and a new lighthouse. (Courtesy of Monroe County Library, Key West.)

Debate swirls around the origin of the name Cayos de Vacas. In Spanish, vaca means cow; some suggest that Spanish explorers spotted wild cows grazing on these islands. There has been no evidence found to prove the presence of cows, however. Cayos Vacas may have instead been inspired by the sight of vacas marinas—sea cows or manatees. After Spain transferred Florida to the United States in 1821, the original Spanish “Cayos de Vacas” or “Cayos Vacas” evolved into “Key Vacas.” From the early Spanish colonial period into the 1800s, the name Key Vacas usually referred to a small collection of islands, rather than a single isle. Eventually, people began calling the largest island Key Vaca and later reversed the words to the current name, Vaca Key. A 1930s US Coast and Geodetic Survey gives some clues about two additional Middle Keys names: apparently, Knight’s Key “was named after the original settler” and Grassy Key was also “named after an old settler and not because it was partially covered with grass.” (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

This J.B. Holder illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows a wrecker in the Florida Keys. In addition to Key West and Indian Key, Key Vacas gradually emerged as a headquarters for the Florida Keys wrecking industry. In the 1820s and 1830s, enterprising wreckers used this new strategic location as a homeport as they patrolled the Florida Reef for ships in distress. In return for rescuing crew and cargo, wreckers received a percentage of the freight they salvaged. Two wreckers, Joshua Appleby and John Fiveash, chose Key Vacas as the base for their operations in 1822 or 1823. Appleby even advertised their settlement, which they called Port Monroe, in the Floridian of Pensacola newspaper. Their 1823 “Notice to Mariners” in the Ship News reports that the place boasts “the advantages of a good and spacious harbor.” The advertisement adds that “at present there are four families residing at this place; corn, potatoes, beans, onions, cotton and all the West Indies fruit thrives rapidly and surpass our most sanguine expectations.” (Jerry Wilkinson collection.)

Commodore David Porter of the Key West antipiracy squadron heard of shady wrecking practices taking place off Key Vacas. According to historian John Viele, wrecker Joshua Appleby and the captain of Colombian schooner La Centilla were conspiring to deliberately ground ships and sharing profits from the salvage. Porter was not amused by the fraud and sent Lt. Stephen Rogers to intercept the culprits. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

In July 1823, Lieutenant Rogers sailed a sloop-of-war from Porter’s “mosquito fleet” to Key Vacas. There he arrested Joshua Appleby. However, the US secretary of the Navy later informed Porter that the wrecker’s “offense does not amount to a positive violation of any law of the United States.” Appleby was released from prison, although he never returned to wrecking at Key Vacas. (Courtesy of Monroe County Library, Key West.)

Charles Howe, pictured here, purchased Key Vacas and nearby islands in 1827. Earlier in 1814, Don Francisco Ferreira had received this property in a Spanish land grant. Ferreira sold Key Vacas, Boot Key, Viper Key, and Knight’s Key to his lawyer Isaac Cox, then Cox sold them to Howe. Strangely enough, none of the three owners ever made a permanent home there. (Courtesy of Monroe County Library, Key West.)

Bahamian mariners fished and salvaged wrecks along the Florida Reef in the early 1800s, when Florida belonged to Spain. Once Florida became US territory, Bahamians began settling here in earnest. In the 1830s, a small Bahamian community (later called Conch Town) grew on Key Vacas. As this J.B. Holder drawing illustrates, “Conch” was the nickname Americans gave Bahamians, given their habit of eating that strange-looking sea mollusk. (Jerry Wilkinson collection.)

This 1845 election document records the name of Key Vacas settler Temple Pent. Bahamian sea captain Pent, his wife, Mary Kemp Pent, and their children arrived on Key Vacas in the 1830s. Temple and Mary’s son John was the first white child born in the Middle Keys. For three decades, the Pent family made their home here, although work at times pulled Temple Sr. away. After winning election as a Florida territorial representative and then senator, Temple spent time in Tallahassee, and later he served as keeper of the Cape Florida Lighthouse. The 1860 Florida census shows several Pents living on Key Vacas: Temple and Mary; John; David; Edward; Elizabeth; Temple Jr., his wife, Elizabeth, and their children, William, Charlotte, and Temple; Anthony, his wife, Rebecca, and their children, Julia and James; and Alonzo, his wife, Mary, and their son, little Alonzo, aged two. The only other Key Vacas residents were the Skelton family and Edmond Beasley, who, with John and Edward Pent, later settled Miami’s Coconut Grove. (Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.)

In response to shipwrecks occurring along the Florida Reef, the US government decided to build a series of lighthouses. One of the sites chosen was a mostly submerged section of reef, Sombrero Key. With iron pilings and a cast iron tower, the light rose 147 feet above the ocean. Despite the presence of the lighthouse, ships occasionally did run aground on the corals. (Courtesy of Monroe County Library, Key West.)

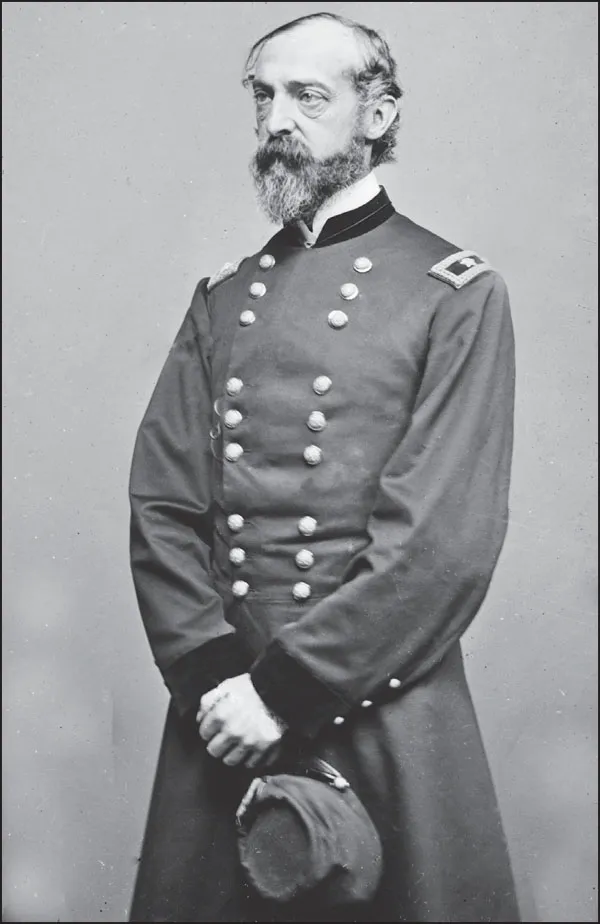

The man who oversaw the 1857–1858 construction of the Sombrero Lighthouse was Lt. George Meade of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. Meade had previously worked on surveying and charting the Florida Reef. During the Civil War, Meade, by then a general, would become famous for his defeat of Robert E. Lee’s army at the Battle of Gettysburg. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

Allegedly, the Middle Keys can claim yet another Civil War connection. After Union forces captured Richmond, Confederate secretary of state Judah Benjamin made an audacious escape through Georgia and Florida, at one point disguised as a Frenchman. Benjamin overnighted off Knight’s Key aboard a 16-foot yawl called, incredibly enough, The Blonde. Then, after boarding another craft, he fled to Bimini in the Bahamas. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

For some mysterious reason, every inhabitant had moved off Key Vacas by 1866. The next recorded settlers were George and Olivia Adderley, a black Bahamian couple who initially arrived in the Keys in 1893. Later, they built a house out of tabby—a mixture of shell, sand, and lime—that can still be seen at the Crane Point Museum and Nature Center. (Photograph by Ebyabe, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.)

Two

THE RAILROAD COMES

TO MARATHON

TO MARATHON

In the early 1900s, few people braved the tropical heat, mosquitoes, isolation, and scarcity of fresh water in the Middle Keys until the Florida East Coast Railway arrived. Then a handful of Conch settlers found th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Cayos de Vacas to Key Vacas

- 2. The Railroad Comes to Marathon

- 3. New Beginnings

- 4. Tourism Booms

- 5. Hurricane Donna

- 6. Community Life

- 7. From the Sea

- Bibliography