eBook - ePub

Vanished Houston Landmarks

Mark Lardas

This is a test

Share book

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Vanished Houston Landmarks

Mark Lardas

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Although it is sometimes called a town without a history, Houston actually possesses the kind of sprawling past that includes a frontier port, a moon landing and a supermarket that contributed to the fall of the Soviet Union. In fact, there is so much history that much has been forgotten. Visit the landmarks of that neglected heritage, from the Cotton Exchange to Astroworld. Dropping in on legendary spots like Shamrock and Gilley's Club, Mark Lardas tells the stories of a Houston that has largely disappeared from the public eye.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Vanished Houston Landmarks an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Vanished Houston Landmarks by Mark Lardas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General1.

THE PERIPATETIC ALLEN’S LANDING

One of the most cherished spots in Houston is Allen’s Landing. This park on the south bank of Buffalo Bayou, where it meets White Oak Bayou, marks the spot where the steamboat Laura made its first landing at the new city of Houston on January 27, 1837, opening the port for business. Even the Handbook of Texas gives Allen’s Landing the status of being the spot where Laura first docked. Today, the city of Houston possesses one of the largest seaports in the United States, which makes the Laura’s arrival a “Plymouth Rock” moment—one where the course of history changed for the better. On its webpage, the Buffalo Bayou Partnership proclaims Allen’s Landing as Houston’s founding place and as “Houston’s most significant and historic site.” Make no mistake, Allen’s Landing deserves the title of Houston’s original port, but was it really Houston’s “Plymouth Rock,” the site of Laura’s first landing? The answer is a definite maybe. Untangling truth from myth requires a trip to the past, to the story of Houston’s founding.

John and Augustus Allen were brothers and land speculators originally from New York. Augustus had briefly been a mathematics professor at the Polytechnic Institute at Chittenango, New York. By 1833, they were both in Louisiana considering the opportunities that were available to them in Texas. In 1836, shortly after the Texas War of Independence, the two were in Galveston, thinking about where to set up a city. Their plan was similar to the one used by Texas subdivision developers today: secure a title to a plot of land, divide it into lots after surveying a grid of streets, promote the development, sell the lots and get rich. Today’s developers have to pave streets, set up utilities, provide sidewalks and construct houses and commercial buildings, but back in 1836, things were simpler. There were no electric easements to worry about, water and sewer lines were all wells that were dug by the landowner and streets were often just graded dirt and cleared pathways. Back then, just as today, the three keys to a successful development were location, location and location. You could put up a town anywhere, but people would not come to that town to buy lots unless they had a good reason to.

Galveston Island originally attracted them because it was a natural seaport and was the best location for carrying cargo out of the newly born Republic of Texas. It was the only location on the Texas coast that offered an anchorage inside the coastal barrier islands with a deep-water channel leading to it. These features protect ships from the storms that are kicked up in the Gulf of Mexico. Before the railroad, most goods traveled by water; the only alternative was to transport goods in wagons drawn by animals. Setting up a city on Galveston Island would have set the brothers on a path to wealth. However, when they arrived, they discovered that others had already had the same idea and secured a title to 4,605 acres of land on the island that would become the City of Galveston. While John and Augustus did invest in the Galveston City Company, they wanted to be more than junior partners. They wanted their own city.

They still wanted to establish a town on a waterway. Goods had to get to Texas’s interior somehow, which meant they had to travel along Texas’s rivers. Only bulk goods, like hides and cotton, could be transported commercially by wagon for about thirty miles. Shipping much more than that in addition to the cost of the fodder that it took to feed the livestock pulling the wagons would literally eat the profits. Everyone in Texas’s interior wanted to cart their produce to the nearest river and load it onto barges or the new steamboats for shipment to a seaport. The main rivers that feed into Galveston Bay are the Trinity River, the San Jacinto River and Buffalo Bayou. In 1836, Texas’s most developed area was to the west and north of the present-day city of Houston. Most goods that were shipped from that area took the Brazos River to Velasco. The modern-day city is at the mouth of the Brazos, an open roadstead that offers no shelter from Gulf storms.

There was a river port on Buffalo Bayou that offered an obvious route to Galveston’s sheltered harbor, bypassing Velasco. The ideal spot for such a town was the head of navigation—the farthest point above the mouth of Buffalo Bayou that could be reached by steamboats. The problem was that the idea to place a town on this piece of land had been just as obvious as the notion that Galveston Island would make a great place for a seaport. Nearly a dozen other empresarios had tried their hand at starting a river port on Buffalo Bayou before the Allen brothers arrived. Not all of them got their projects launched, but by 1836, there were already eight ports on Buffalo Bayou, starting with Lynchburg, where Buffalo Bayou ended, and proceeding west to New Washington, Powhattan, Scottsburg, Louisville, San Jacinto, Hamilton and, finally, Harrisburg. However, with the exception of Lynchburg, New Washington and Harrisburg, these were all notional cities. Given the competition, the Allens needed an edge; they had to set up their city at the head of navigation. The problem with this plan was that Harrisburg was already at the head of navigation—the spot was taken. So, the Allens’ next move was to try to buy Harrisburg.

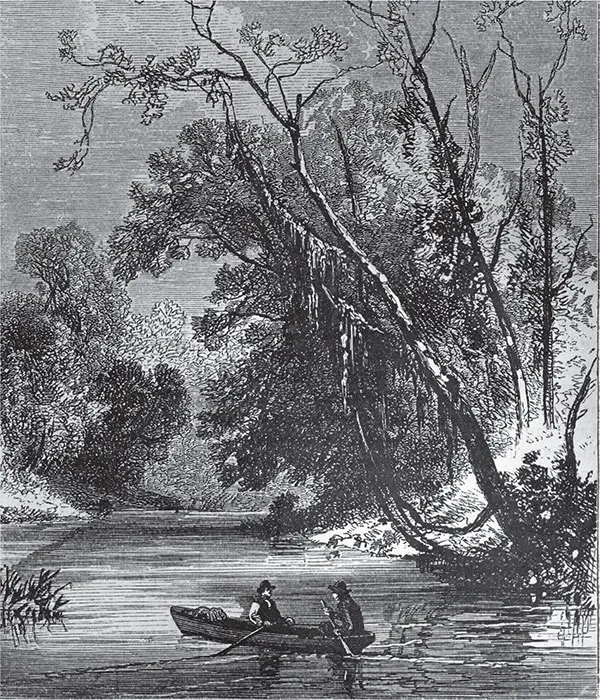

In 1837, when Francis Lubbock and friends borrowed the Laura to row past Buffalo Bayou to White Oak Bayou, Houston looked similar to this image, with a snag-choked shore and trees hanging over the river. Author’s collection.

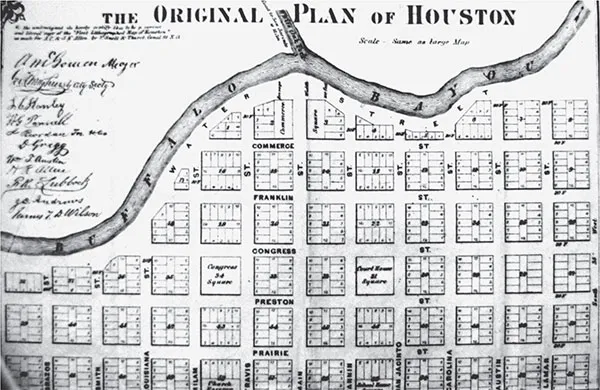

It took three days for the Laura to travel the five miles between Harrisburg and Houston. While legend holds that it landed at the foot of Main Street, the boat most likely stopped at the first street it recognized—either Lamar or Austin, as shown on this map. Courtesy of the Houston Maritime Museum.

When Harrisburg’s founder died in 1929, the Allens thought the town might be available to purchase. However, the title to the town was tied up in an inheritance squabble, and by 1836, the legal battle was still going strong. Balked, the Allens tried something audacious: they redefined the location of the head of navigation for Buffalo Bayou. Unclaimed land was available five miles upriver from Harrisburg, where White Oak Bayou flows into Buffalo Bayou. The brothers declared that piece of land was the true head of navigation of Buffalo Bayou and claimed the intersection of White Oak and Buffalo Bayous offered a natural turning basin. After they bought land there in August 1836, the Allens platted a new town on the land and placed Main Street right at the intersection of the two bayous.

In the typical style of land developers, they gave the town a captivating name: Houston, after the Republic of Texas’s biggest hero, Sam Houston. Houston was Texas’s George Washington; he was the commander of the victorious Texian army during the Republic’s war for independence and the first president of the Republic. Furthermore, the brothers donated some of their town’s land for the Republic’s capitol building. Their offer was accepted by a cash-strapped Texian legislature, making Houston the capital as well as an essential port.

Claiming that Houston, rather than Harrisburg, was Buffalo Bayou’s head of navigation could charitably be called Texas brag. Buffalo Bayou, between Houston and Harrisburg, was deep enough for the steamboats of the day, but it was narrow and twisting. The stretch could be dredged, widened and straightened out enough to make it reasonably navigable, but all of that would take money that the Allens did not have in 1836. The improvement of the five-mile stretch would have left Houston only fifteen miles east of the Brazos agricultural area and just thirty-five miles from San Filipe de Austin, the oldest Anglo colony in Texas. Five miles significantly cut the journey from the Brazos—if Houston really was head of navigation. Skeptics abounded, however; many wondered whether the brothers were stretching the truth. Because of this doubt, the Allens had to demonstrate that they could get a steamboat to Houston.

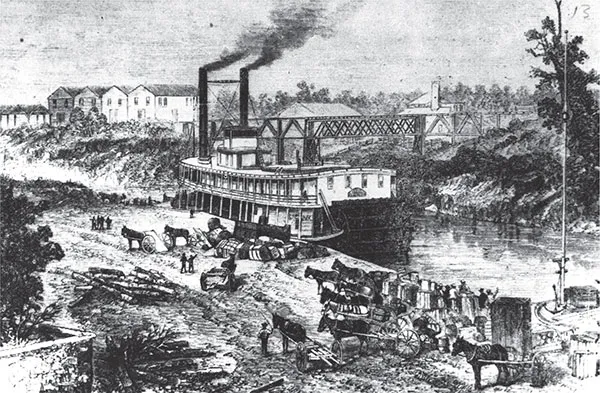

For many years, the foot of Main Street was Houston’s main wharf. This picture shows how it would have appeared in the years before the Civil War. Courtesy of the University of Houston Digital Archive Library.

The brothers chartered the steamboat Laura for the trip to Houston. At 65 feet long, the Laura was the smallest steamboat on the Texas rivers at the time. The steamboat departed from Galveston in early January 1837. Aboard the boat was John Allen, Mosely Baker (a San Jacinto hero), Benjamin C. Franklin (a Texas lawyer—not the founding father) and Francis Lubbock (a future Texas governor). It took the crew only a few days to reach Harrisburg, and they spent much of that time trying to free the boat after it was grounded in Galveston Bay. The final five miles of their journey consumed three days, as the boat only averaged 367 feet per hour. It was the first time a steamboat had ever traveled that stretch of Buffalo Bayou, so the crew spent a lot of time clearing the bayou of obstructions. Removing snags and heaving logs out of the bayou proved an all-hands-on-deck operation. The Laura was tied up each night while the passengers went ashore to party.

The brothers began selling lots in Houston on January 19, a day chosen because the Laura was supposed to have reached the town by then. Lubbock and some of the other crew members got impatient with the steamboat’s slow progress, so they borrowed the Laura’s yawl and went up Buffalo Bayou seeking Houston. Lubbock later wrote of the adventure:

So little evidence could we see of a landing that we passed by the site and ran into White Oak Bayou, only realizing that we must have passed the city when we struck in the brush. We then backed down the bayou, and by close observation, discovered a road or street laid off from the water’s edge. Upon landing, we found stakes and footprints, indicating that we were in the town tract.

A few days later, the Laura finally arrived in Houston. No one really knows the exact date of the Laura’s landing, but the Handbook of Texas marks it as January 27. However, nineteenth-century historians claimed the date was January 22. Whether or not the Laura was tied up at Allen’s Landing—today’s foot of Main Street—is equally uncertain, but in my opinion, it is doubtful that the boat landed there. Lubbock’s account says that the fork of White Oak and Buffalo Bayous was easy to miss. Houston itself only consisted of surveyors’ stakes and muddy roads; there were no buildings in town, only a few tents, which were not within sight of the river.

The original layout of Houston shows Main Street in the center of eleven streets that were perpendicular to Buffalo Bayou. To the east of Main Street were Fannin, San Jacinto, Carolina, Austin and Lamar (today’s La Branch) Streets. The Laura had already spent three days battling the five miles between Harrisburg and Houston, so rather than struggle another few hundred yards to Main Street, it is much more likely that the captain of the Laura declared victory at the first set of surveyor’s stakes he saw and tied up there. Why would he have risked hitting a snag trying to find Main Street? So, where did the Allens land? Pick a spot. All the streets between Main and Lamar Streets were, at the time, just mud patches marked by stakes. While it is sentimental to think that the Laura landed at today’s Allen’s Landing, one can make just as good of an argument that the boat landed at Lamar, or any of the other streets that led up to Main Street.

In the 1890s, the Port of Houston began moving downstream from its Main Street location. Plans were in hand to transform Houston into a major seaport, and since it would have been too difficult to dredge the bayou to a depth of twenty-five feet all the way to Main Street, a more practical spot for the terminus of the Houston Ship Channel was chosen. Its new location was five miles downstream from Main Street, where Harrisburg—long ago absorbed into Houston—was located.

The area on Main Street only became Allen’s Landing in the 1960s, when the commercial port departed downstream and the waterfront in downtown Houston devolved into an unattractive dump. The Houston Chamber of Commerce wanted to revitalize the neglected area of downtown and helped spearhead an effort to build a park there in celebration of Houston’s maritime heritage. Charlie Lansden, the then-director of the chamber’s Community Betterment Division dubbed that section of Buffalo Bayou Allen’s Landing as a marketing ploy. Allen’s Landing sounded more interesting than “The Foot of Main Street,” “Old Port” or something that was more historically accurate. Lansden’s tactic worked, and the two-acre park was dedicated as Allen’s Landing Memorial Park in 1967. The area was transformed from a blighted neighborhood of the 1960s to the Houston treasure today; it helped Houston rediscover and embrace its maritime heritage.

Allen’s Landing as it appears today. It is a cherished park in the middle of downtown Houston, at the meeting point of Main Street and Buffalo Bayou—the spot that made Houston. Photograph by author.

Whether or not the Laura landed there, the corner of Main and Water Streets (today’s Allen’s Landing) is historically significant, as it was the site of the original Port of Houston. Even if Laura tied up somewhere else in January 1837, Houston’s first wharves were built at the foot of Main Street shortly after the boat’s famous trip. Over time, Buffalo Bayou was deepened and widened, with a ten-foot-deep channel that reached the foot of Main Street. For the next sixty years, the foot of Main Street was the heart of Houston’s port district. The port was the reason for Houston’s existence and remains a major industry in the city today—it should be celebrated. Today, Allen’s Landing is one of the trendier spots in Houston’s waterfront district and is known for its annual spring festival. A replica of the original port has been built in the park. It is one of the jewels of central Houston and is surrounded by the University of Houston–Downtown.

2.

THE LOST SISTERS

The Battle of San Jacinto settled the outcome of the Texas War of Independence and, as a result, decided the eventual shape of the United States. Roughly 2,100 men—some 900 Texians and 1,300 Mexicans—fought on marshy prairie near the junction of Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River on April 21, 1836. The Texian army charged across the field at 4:30 p.m. and caught the Mexican army napping. Twenty minutes later, the Mexican army routed and fled the field, and the Texians eventually captured Santa Anna de Lopez, the Mexican commander and president. Santa Anna eventually traded the independence of Texas for his own freedom, thus concluding the new Texas Republic’s struggle to gain independence from Mexico.

Every April, a reenactment of the Battle of San Jacinto is held at Battleground Park, where the battle was fought. If you have ever attended a reenactment, you probably watched the artillery duel that precedes each battle. The Texians fire two cannons, and the Mexicans respond with one. The two Texian cannons at the battle were called the Twin Sisters. The Texas War of Independence generated tremendous support throughout the United States. In Cincinnati, Ohio, the citizens raised funds to cast two cannons that they later donated to the Texian forces. The resulting iron smoothbores were cast at the foundry of Greenwood and Webb in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Little is known about the guns, and they have been variously described as four-pounders and six-pounders; their weight and dimensions are unknown. Some sources even claim the guns were made of brass, which is unlikely since Greenwood and Webb was an iron foundry. Greenwood and Webb was still in business in the 1980s, when some Texans wanted replicas of the guns made for the 1986 Texas sesquicentennial. Alas, time had worked its vanishing act, and all of the drawings and plans the foundry had for the Twin Sisters had disappeared by then. The only fact about the cannons that is known for certain is that they arrived in Texas in time for the Battle of San Jacinto and helped secure the Texian victory. The cannons are thought to still be in Houston, but no one knows where. In the ...