![]()

FIRST BULL RUN: AN OVERVIEW

Prelude to Battle

On 15 April 1861, the day after South Carolina military forces had attacked and captured Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring an insurrection against the laws of the United States. Earlier, South Carolina and seven other Southern states had declared their secession from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

To suppress the rebellion and restore Federal law in the Southern states, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers with ninety-day enlistments to augment the existing U.S. Army of about 15,000. He later accepted an additional 40,000 volunteers with three-year enlistments and increased the strength of the U.S. Army to almost 20,000. Lincoln’s actions caused four more Southern states, including Virginia, to secede and join the Confederacy, and by 1 June the Confederate capital had been moved from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia.

In Washington, D.C., as thousands of volunteers rushed to defend the capital, General in Chief Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott laid out his strategy to subdue the rebellious states. He proposed that an army of 80,000 men be organized and sail down the Mississippi River and capture New Orleans. While the Army “strangled” the Confederacy in the west, the U.S. Navy would blockade Southern ports along the eastern and Gulf coasts. The press ridiculed what they dubbed as Scott’s “Anaconda Plan.” Instead, many believed the capture of the Confederate capital at Richmond, only one hundred miles south of Washington, would quickly end the war.{1}

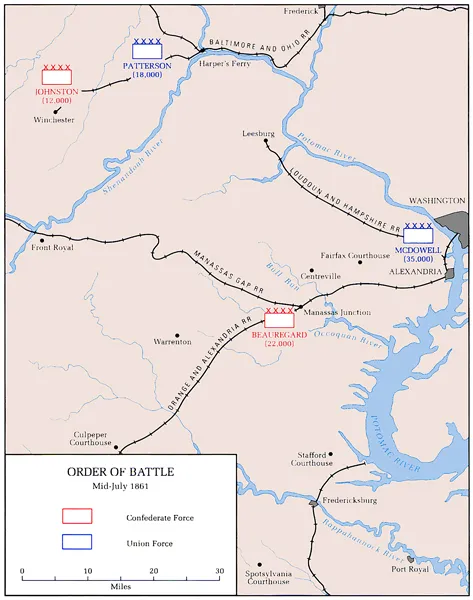

By July 1861 thousands of volunteers were camped in and around Washington. Since General Scott was seventy-five years old and physically unable to lead this force, the administration searched for a more suitable field commander. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase championed fellow Ohioan, 42-year-old Maj. Irvin McDowell. Although McDowell was a West Point graduate, his command experience was limited. In fact, he had spent most of his career engaged in various staff duties in the Adjutant General’s Office. While stationed in Washington he had become acquainted with Chase, a former Ohio governor and senator. Now, through Chase’s influence, McDowell was promoted three grades to brigadier general in the Regular Army and on 27 May was assigned command of the Department of Northeastern Virginia, which included the military forces in and around Washington.{2} (Map 1)

McDowell immediately began organizing what became known as the Army of Northeastern Virginia, 35,000 men arranged in five divisions. Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler’s 1st Division, the largest in the army, contained four brigades, led by Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck, Col. Erasmus Keyes, Col. William T. Sherman, and Col. Israel B. Richardson. Col. David Hunter commanded the 2d Division of two brigades. These were led by Cols. Andrew Porter and Ambrose E. Burnside. Col. Samuel P. Heintzelman commanded three brigades of the 3d Division, led by Cols. William B. Franklin, Orlando B. Willcox, and Oliver O. Howard. The 4th Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Theodore Runyon, contained seven regiments of New Jersey and one regiment of New York volunteer infantries. Col. Dixon S. Miles’ 5th Division contained two brigades, commanded by Cols. Louis Blenker and Thomas A. Davies. McDowell’s army also had ten batteries of artillery and a battalion of Regular cavalry.

Under public and political pressure to begin offensive operations, McDowell was given very little time to train the newly inducted troops. Units were instructed in the maneuvering of regiments, but they received little or no training at the brigade or division level. In fact, on one occasion, when McDowell reviewed eight infantry regiments at one time, the visiting General Scott chastised him for “trying to make a big show.”{3}

While McDowell organized the Army of Northeastern Virginia, a smaller Union command was organized and stationed northwest of Washington, near Harper’s Ferry. Commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson, 18,000 men of the Department of Pennsylvania protected against a Confederate incursion from the Shenandoah Valley. Although almost seventy years old and a veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, Patterson had been given a three-month volunteer officer’s commission in April 1861 and now commanded a varied force of Pennsylvania volunteers.

Map 1

At Winchester, Virginia, southwest of Patterson’s command, were 12,000 Confederate troops of the Army of the Shenandoah under 54-year-old General Joseph E. Johnston. Before the war Johnston had served as quartermaster general of the United States Army. Now, as a Confederate commander, he was charged with defending the Shenandoah Valley and, if necessary, going to the support of Brig. Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard’s command at Manassas Junction. The Army of the Shenandoah consisted of five infantry brigades: the 1st, commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson; the 2d, commanded by Col. Francis S. Bartow; the 3d, commanded by Brig. Gen. Barnard E. Bee; the 4th, commanded by Col. Arnold Elzey; and the 5th, commanded by Brig. Gen. E. Kirby Smith. In addition to the infantry, there were twenty pieces of artillery and about 300 Virginia cavalrymen under Col. J. E. B. Stuart.

Thirty miles southwest of Washington, at Manassas Junction, the 22,000-man Confederate Army of the Potomac blocked McDowell’s route to Richmond and defended the junction of the Orange and Alexandria and Manassas Gap Railroads. That force was commanded by 43-year-old General Beauregard, a former West Point classmate of McDowell. Beauregard had commanded the Confederate troops that had forced the surrender of Fort Sumter, and the “Hero of Sumter” had been assigned to the Confederate army being organized at Manassas Junction. The Army of the Potomac was organized into seven infantry brigades. These were the 1st Brigade, under Brig. Gen. Milledge L. Bonham; 2d Brigade, under Brig. Gen. Richard S. Ewell; 3d Brigade, under Brig. Gen. David R. Jones; 4th Brigade, under Brig. Gen. James Longstreet; 5th Brigade, under Col. Philip St. George Cocke; 6th Brigade, under Col. Jubal A. Early; and 7th Brigade, under Col. Nathan G. Evans. Beauregard’s army also contained thirty-nine pieces of field artillery and a regiment of Virginia cavalry.

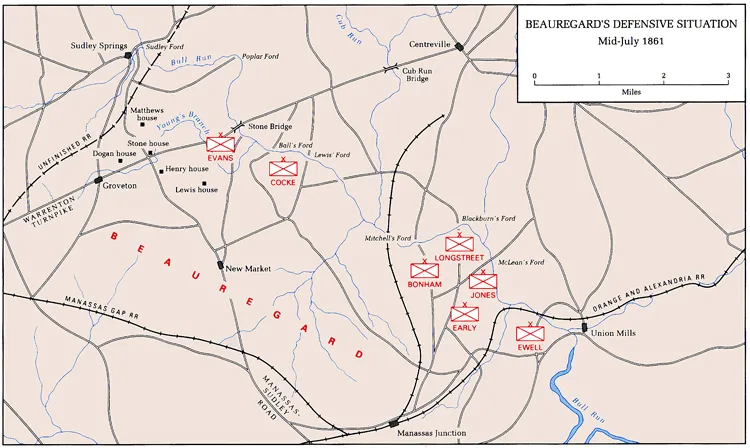

Expecting McDowell to march on Manassas Junction by way of Centreville, Beauregard began preparing a defensive position along the south bank of Bull Run, a small creek flowing into the Occoquan River. (Map 2) Beauregard placed his right flank near the railroad bridge at Union Mills, extending the line northward over seven miles along Bull Run to the Stone Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike. General Ewell’s brigade was located near Union Mills; General Jones’ brigade was at McLean’s Ford, supported by the brigade of Colonel Early; General Longstreet’s brigade was placed at Blackburn’s Ford; General Bonham’s brigade was at Mitchell’s Ford; Colonel Cocke’s brigade was between Lewis’ and Ball’s fords; and Colonel Evans’ brigade held the army’s left flank at the Stone Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike.{4}

McDowell planned to march his army toward Manassas Junction on 9 July and, while Patterson held Johnston’s army in the Shenandoah Valley, defeat Beauregard’s command. However, a lack of sufficient supplies postponed the maneuver for a week. Prior to the operation, McDowell warned the War Department that unless Johnston was prevented from reinforcing Beauregard, McDowell felt he had little chance of victory. General Scott assured McDowell that if Johnston did manage to slip out of the valley “he would have Patterson on his heels.”{5}

Map 2

Finally, on 16 July, McDowell’s army headed for Manassas Junction. Amid cries of “On to Richmond,” the excited soldiers marched south, confident that in a few days the war would be over, won by one grand battle. Since some of his regiments wore gray uniforms like many of the Confederate units, McDowell ordered that U.S. flags be displayed prominently at all times to prevent units from firing at each other.{6}

By the following day General Beauregard had been alerted to the Union advance and asked the Confederate government for reinforcements. An independent infantry brigade stationed at Fredericksburg, commanded by Brig. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes, was ordered to Manassas Junction, and in Richmond six companies of South Carolina infantry of the independent Hampton Legion, commanded by Col. Wade Hampton, boarded trains and hurried north.

McDowell had hoped to have his army at Centreville by 17 July, but the troops, unaccustomed to marching, moved in starts and stops. Along the route soldiers often broke ranks to wander off to pick apples or blackberries or to get water, regardless of the orders of their officers to remain in ranks. By 1130, 17 July, the head of McDowell’s army, Tyler’s division, had only reached Fairfax Courthouse. McDowell wanted the men to push on to Centreville, but they were too exhausted to continue and camped near Fairfax.

It was not until 1100 on 18 July that Tyler’s division arrived at Centreville. While McDowell brought up the rest of the army, Tyler was ordered to observe the roads to Bull Run and Warrenton but under no circumstances to bring on an engagement. However, Tyler led a portion of Colonel Richardson’s brigade to Blackburn’s Ford where it became engaged with troops of General Longstreet. An aide to McDowell, accompanying the expedition, reminded Tyler of the commanding general’s admonition not to bring on an engagement, but Tyler ordered up the remainder of Richardson’s brig...

![Staff Ride Guide - The Battle Of First Bull Run [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018240/9781782894599_300_450.webp)