![U.S. Marine Operations In Korea 1950-1953: Volume III - The Chosin Reservoir Campaign [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018645/9781786254283_300_450.webp)

eBook - ePub

U.S. Marine Operations In Korea 1950-1953: Volume III - The Chosin Reservoir Campaign [Illustrated Edition]

- 406 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

U.S. Marine Operations In Korea 1950-1953: Volume III - The Chosin Reservoir Campaign [Illustrated Edition]

About this book

Includes over 50 photos and 30 maps.

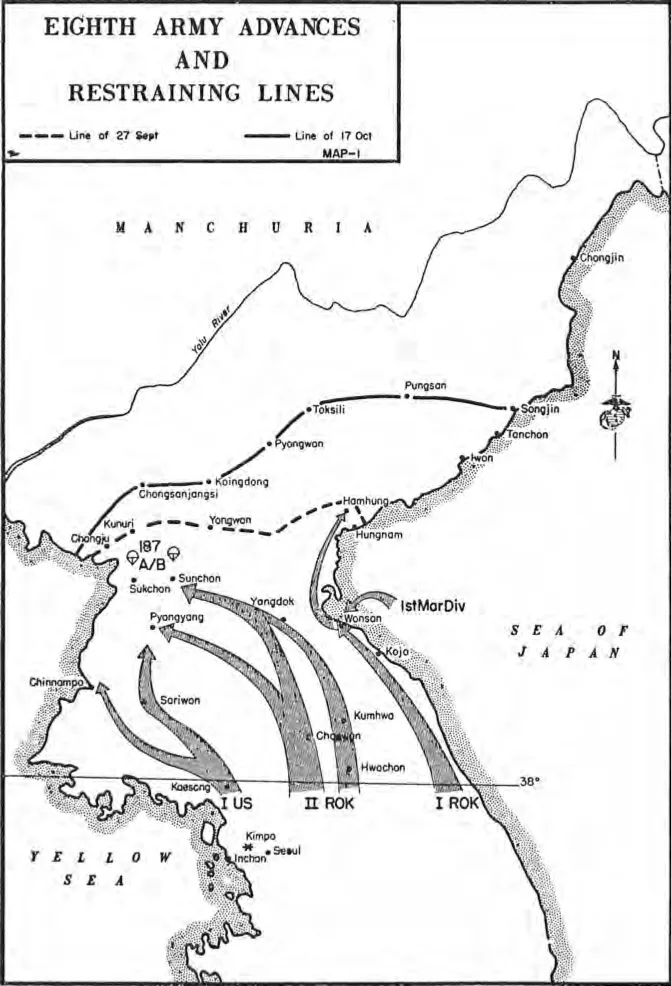

THIS IS THE THIRD in a series of five volumes dealing with the operations of the United States Marine Corps in Korea during the period 2 August 1950 to 27 July 1953. Volume III presents in detail the operations of the 1st Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing as a part of X Corps, USA, in the Chosin Reservoir campaign.

The time covered in this book extends from the administrative landing at Wonsan on 26 October 1950 to the Hungnam evacuation which ended on Christmas Eve. The record would not be complete, however, without reference to preceding high-level strategic decisions in Washington and Tokyo which placed the Marines in northeast Korea and governed their employment.

"THE BREAKOUT of the 1st Marine Division from the Chosin Reservoir area will long be remembered as one of the inspiring epics of our history. It is also worthy of consideration as a campaign in the best tradition of American military annals.

The ability of the Marines to fight their way through twelve Chinese divisions over a 78-mile mountain road in sub-zero weather cannot be explained by courage and endurance alone. It also owed to the high degree of professional forethought and skill as well as the "uncommon valor" expected of all Marines.

When the danger was greatest, the 1st Marine Division might have accepted an opportunity for air evacuation of troops after the destruction of weapons and supplies to keep them from falling into the enemy's hands. But there was never a moment's hesitation. The decision of the commander and the determination of all hands to come out fighting with all essential equipment were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Marine Corps."- Gen. Pate

THIS IS THE THIRD in a series of five volumes dealing with the operations of the United States Marine Corps in Korea during the period 2 August 1950 to 27 July 1953. Volume III presents in detail the operations of the 1st Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing as a part of X Corps, USA, in the Chosin Reservoir campaign.

The time covered in this book extends from the administrative landing at Wonsan on 26 October 1950 to the Hungnam evacuation which ended on Christmas Eve. The record would not be complete, however, without reference to preceding high-level strategic decisions in Washington and Tokyo which placed the Marines in northeast Korea and governed their employment.

"THE BREAKOUT of the 1st Marine Division from the Chosin Reservoir area will long be remembered as one of the inspiring epics of our history. It is also worthy of consideration as a campaign in the best tradition of American military annals.

The ability of the Marines to fight their way through twelve Chinese divisions over a 78-mile mountain road in sub-zero weather cannot be explained by courage and endurance alone. It also owed to the high degree of professional forethought and skill as well as the "uncommon valor" expected of all Marines.

When the danger was greatest, the 1st Marine Division might have accepted an opportunity for air evacuation of troops after the destruction of weapons and supplies to keep them from falling into the enemy's hands. But there was never a moment's hesitation. The decision of the commander and the determination of all hands to come out fighting with all essential equipment were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Marine Corps."- Gen. Pate

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access U.S. Marine Operations In Korea 1950-1953: Volume III - The Chosin Reservoir Campaign [Illustrated Edition] by Lynn Montross,Captain Nicholas A. Canzona USMC in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I — Problems Of Victory

Decision to Cross the 38th Parallel—Surrender Message to NKPA Forces—MacArthur’s Strategy of Celerity—Logistical Problems of Advance—Naval Missions Prescribed—X Corps Relieved at Seoul—Joint Planning for Wonsan Landing

IT IS A LESSON of history that questions of how to use a victory can be as difficult as problems of how to win one. This truism was brought home forcibly to the attention of the United Nations (UN) heads, both political and military, during the last week of September 1950. Already, with the fighting still in progress, it had become evident that the UN armies were crushing the forces of Communism in Korea, as represented by the remnants of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA).

Only a month before, such a result would have seemed a faint and unrealistic hope. Late in August the hard-pressed Eighth U. S. Army in Korea (EUSAK) was defending that southeast corner of the peninsula known as the Pusan Perimeter.

“Nothing fails like success,” runs a cynical French proverb, and the truth of this adage was demonstrated militarily when the dangerously over-extended NKPA forces paid the penalty of their tenuous supply line on 15 September 1950. That was the date of the X Corps amphibious assault at Inchon, with the 1st Marine Division as landing force spearheading the advance on Seoul.

X Corps was the strategic anvil of a combined operation as the Eighth Army jumped off next day to hammer its way out of the Pusan Perimeter and pound northward toward Seoul. When elements of the two UN forces met just south of the Republic of Korea (ROK) capital on 26 September, the routed NKPA remnants were left only the hope of escaping northward across the 38th parallel. {1}

The bold strategic plan leading up to this victory—one of the most decisive ever won by U. S. land, sea and air forces—was largely the concept of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, USA, who was Commander in Chief of the United Nations Command (CinCUNC) as well as U. S. Commander in Chief in the Far East (CinCFE). It was singularly appropriate, therefore, that he should have returned the political control of the battle-scarred ROK capital to President Syngman Rhee on 29 September. Marine officers who witnessed the ceremony have never forgotten the moving spectacle of the American general and the fiery Korean patriot, both past their 70th birthdays, as they stood together under the shell-shattered skylight of the Government Palace. {2}

Decision to Cross the 38th Parallel

“Where do we go from here?” would hardly have been an oversimplified summary of the questions confronting UN leaders when it became apparent that the NKPA forces were defeated. In order to appraise the situation, it is necessary to take a glance at preceding events.

As early as 19 July, the dynamic ROK leader had made it plain that he did not propose to accept the pre-invasion status quo. He served notice that his forces would unify Korea by driving to the Manchurian border. Since the Communists had violated the 38th Parallel, the aged Rhee declared, this imaginary demarcation between North and South no longer existed. He pointed out that the sole purpose of the line in the first place had been to divide Soviet and American occupation zones after World War II, in order to facilitate the Japanese surrender and pave the way for a democratic Korean government.

In May 1948, such a government had come about in South Korea by popular elections, sponsored and supervised by the UN. These elections had been scheduled for all Korea but were prohibited by the Russians in their zone. The Communists not only ignored the National Assembly in Seoul, but also arranged their own version of a governing body in Pyongyang two months later. The so-called North Korean People’s Republic thus became another of the Communist puppet states set up by the USSR.

That the United Nations did not recognize the North Korean state in no way altered its very real status as a politico-military fact. For obvious reasons, then, all UN decisions relating to the Communist state had to take into account the possibility of reactions by Soviet Russia and Red China, which shared Korea’s northern boundary.

At the outbreak of the conflict on 25 June 1950, the UN Security Council had, by a vote of 9–0, called for an immediate end to the fighting and the withdrawal of all NKPA forces to the 38th Parallel. {3} This appeal having gone unheeded, the Council on 27 June recommended “...that the Members of the United Nations furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.”{4} It was the latter authorization, supplemented by another resolution on 7 July, that led to military commitments by the United States and to the appointment of General MacArthur as over-all UN Commander.

These early UN actions constituted adequate guidance in Korea until the Inchon landing and EUSAK’S counteroffensive turned the tide. With the NKPA in full retreat, however, and UN Forces rapidly approaching the 38th Parallel, the situation demanded re-evaluation, including supplemental instructions to the military commander. The question arose as to whether the North Koreans should be allowed sanctuary beyond the parallel, possibly enabling them to reorganize for new aggression. It will be recalled that Syngman Rhee had already expressed his thoughts forcibly in this connection on 19 July; and the ROK Army translated thoughts into action on 1 October by crossing the border.

The UN, in its 7 July resolution, having authorized the United States to form a unified military force and appoint a supreme commander in Korea, it fell upon the Administration of President Harry S. Truman to translate this dictum into workaday reality. Aiding the Chief Executive and his Cabinet in this delicate task with its far-reaching implications were the Joint U. S. Chiefs of Staff (JCS). The Army member, General J. Lawton Collins, also functioned as Executive Agent of JCS for the United Nations Command in Korea, thus keeping intact the usual chain of command from the Army Chief of Staff to General MacArthur, who now served both the U. S. and UN. {5}

Late in August, two of the Joint Chiefs, General Collins and Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, USN, had flown to Japan to discuss the forthcoming Inchon landing with General MacArthur. In the course of the talks, it was agreed that CinCUNC’s objective should be the destruction of the North Korean forces, and that ground operations should be extended beyond the 38th Parallel to achieve this goal. The agreement took the form of a recommendation, placed before Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson on 7 September. {6}

A week later, JCS informed MacArthur that President Truman had approved certain “conclusions” relating to the Korean conflict, but that these were not yet to be construed as final decisions. Among other things, the Chief Executive accepted the reasoning that UN Forces had a legal basis for engaging the NKPA north of the Parallel. MacArthur would plan operations accordingly, JCS directed, but would carry them out only after being granted explicit permission. {7}

The historic authorization, based on recommendations of the National Security Council to President Truman, reached General Headquarters (GHQ), Tokyo, in a message dispatched by JCS on 27 September:

“Your military objective is the destruction of the North Korean Armed Forces. In attaining this objective you are authorized to conduct military operations, including amphibious and airborne landings or ground operations north of the 38th Parallel in Korea, provided that at the time of such operations there has been no entry into North Korea by major Soviet or Chinese Communist Forces, no announcement of intended entry, nor a threat to counter our operations militarily in North Korea....”

The lengthy message abounded in paragraphs of caution, reflecting the desire of both the UN and the United States to avoid a general war. Not discounting the possibility of intervention by Russia or Red China, JCS carefully outlined MacArthur’s courses of action for several theoretical situations. Moreover, he was informed that certain broad restrictions applied regardless of developments:

“...under no circumstances, however, will your forces cross the Manchurian or USSR borders of Korea and, as a matter of policy, no non-Korean Ground Forces will be used in the northeast provinces bordering the Soviet Union or in the area along the Manchurian border. Furthermore, support of your operations north or south of the 38th parallel will not include Air or Naval action against Manchuria or against USSR territory.... {8}”

Thus MacArthur had the green light, although the signal was shaded by various qualifications. On 29 September, the new Secretary of Defense, George C. Marshall, told him in a message, “...We want you to feel unhampered tactically and strategically to proceed north of 38th parallel....” {9}

Surrender Message to NKPA Forces

Meanwhile, a step was taken by the U. S. Government on 27 September in the hope that hostilities might end without much further loss or risk for either side. By dispatch, JCS authorized MacArthur to announce, at his discretion, a suggested surrender message to the NKPA. {10} Framed by ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Foreword

- Preface

- Illustrations

- CHAPTER I - Problems Of Victory

- CHAPTER II - The Wonsan Landing

- CHAPTER III - First Blood At Kojo

- CHAPTER IV - Majon-ni and Ambush Alley

- Thus the 1st Marine Division achieved a relative and temporary degree of concentration. The farthest distance between components had been reduced from 130 to less than 60 miles by the middle of November, but a new dispersion of units was already in progress.

- CHAPTER V - Red China to the Rescue

- CHAPTER VI - The Battle of Sudong

- CHAPTER VII - Advance To The Chosin Reservoir

- CHAPTER VIII - Crisis at Yudam-ni

- CHAPTER IX - Fox Hill

- CHAPTER X - Hagaru’s Night of Fire

- CHAPTER XI - Task Force Drysdale

- CHAPTER XII - Breakout From Yudam-ni

- CHAPTER XIII - Regroupment at Hagaru

- CHAPTER XIV - Onward from Koto-ri

- CHAPTER XV - The Hungnam Redeployment

- APPENDIX A - Glossary of Technical Terms and Abbreviations

- APPENDIX B - Task Organization 1st Marine Division

- APPENDIX C - Naval Task Organization

- APPENDIX D - Effective Strength of 1st Marine Division

- APPENDIX E - 1st Marine Division Casualties

- APPENDIX F - Command and Staff List 8 October-15 December 1950

- APPENDIX G - Enemy Order of Battle

- APPENDIX H - Air Evacuation Statistics

- APPENDIX I - Unit Citations

- Chief of Staff, United States Army

- Bibliography