eBook - ePub

A Soldier Unafraid - Letters From The Trenches On The Alsatian Front

- 61 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Soldier Unafraid - Letters From The Trenches On The Alsatian Front

About this book

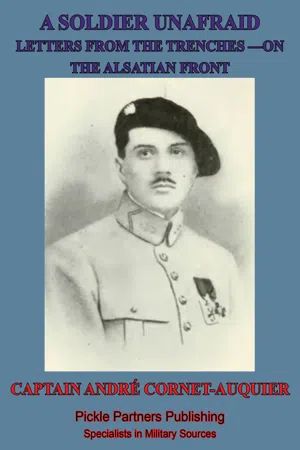

Nearly 1.7 million French soldiers died in the First World War fighting for their homeland against the invading German Armies; it is difficult to comprehend that hecatomb. It is indeed difficult to comprehend that many lost lives, perhaps the only way to do so is in representative figures such as the Unknown Soldier or by the many memoirs and diaries that have been left behind. One such diary is that of Captain André Cornet-Auquier, a passionate but moral man, well-known for his leadership skills in and bravery on the battlefield. The conditions in which he served on the Alsace front were always tough, being often within forty-five yards of the enemy's front lines, his faith in his cause and God sustained him even in the most trying situations. Despite being in the front line fighting for so long his luck ran out in February 1916, mortally wounded by a shell splinter. A symbol of French stoicism and courage he died beloved by his men, one of his sergeants said "It is not a spectacle often witnessed, — that of soldiers, accustomed to face death, weeping like children as they stood round his bier."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Soldier Unafraid - Letters From The Trenches On The Alsatian Front by Captain André Cornet-Auquier, Theodore Stanton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A SOLDIER UNAFRAID

LETTERS FROM THE TRENCHES ON THE ALSATIAN FRONT

Colwyn Bay, North Wales, August 3, 1914.

Dearest Parents: The latest news shows that we are in for war. I learned this yesterday afternoon. When we heard it in the house where I was staying, everybody grew pale. We thereupon had family prayers and sang, “Be with us, Lord.” How beautiful are the words of that hymn. Our host prayed for me and for mama, expressing the hope that she might have God's support in her trial. “We recommend to Thee the mother of our brother,” were his words; “Thou knowest what they are to one another.” I was and am still calm. God is there; fear nothing. And you know I have a military soul. Tell the British uncles that I am proud to fight not only for France but also for England, that dear second native land of mine; and if I must die for those two countries, I shall do so happily, provided only that we are victorious. But I am a French soldier all the same. I shall reach Paris to-morrow, during the day.

Châlon-sur-Saône, August 5.

Tell the English uncles that I shall fight like a Frenchman and die like an Englishman. The order will be Nelson's famous one: “England expects that every man will do his duty!” So let us be of good courage. Hurrah for France and England!

Belley, August 6.

You cannot imagine the delirious enthusiasm of the troops. A British officer whom I met at the Ambérieu station can't get over his surprise at it. I am back again in the military spirit, — a soldier to my fingers' tips.

Belley, August 15.

I shall soon be orderly officer, charged with the police of our barracks. Then you may be sure it will go hard with the saloons.

We have full power over them, and they will find it out, these miserable wretches who inveigle the soldiers in by the back door and get them drunk. Many of us are burning to get to the front. I came here to fight, am full of ardor and ready to do all I can. But here we are hanging about doing nothing, boring ourselves, while others are getting shot down. So the first call for volunteers will find me en route for the firing-line.

Approaching Alsace, August 23.

Dear Mother and Father: I am off to the war. I have made the first fifteen miles all right. The colonel has received me very kindly and I have met many of the soldiers whom I had under me when I was in the service. I am separated from my friend Girard, but as he is in a neighboring battalion we shall often see one another. It seems odd to hear German spoken around you. But you feel, nevertheless, very plainly that you are in France. At Belfort, I saw twenty-four cannon which had been taken from the enemy and met several batches of German prisoners. It seemed queer to see them laughing and joking when we passed them on the road. They consider us “comrades”, the football match being at an end, at least as far as they are concerned. The captain whom I had at Belley cried like a child because he couldn't come with us.

Alsace, August 25.

What a reception we have had! “You are our saviors,” the people said to us this morning. They drink to our health with a “Hurrah for French Alsace!” They are taking good care of us, in fact are really coddling us. But they aren't doing too much for us, for this is hard work we are at. On account of the flying machines, we have to do everything at night. During the past five days I have not slept more than from twelve to fifteen hours; so we are all tired out, though we have plenty to eat. My German is very useful, but the people here are very proud to speak French. The morale is good.

August 27.

The popular sentiment varies in different places. Sometimes we find the inhabitants less French in one spot than in another.

September 4.

I have been under fire for the first time! Oh, the horrors of war! The ravaged villages! How it all tries your nerves! God be with us! I feel that He is with me!

September 10.

I am writing you a few hundred yards from the enemy's lines. I have been lying only two hundred yards from the Germans and I can assure you I kept my eyes open. We are all beat out. It is ten days since I have had a wash, and I haven't had my shoes off for a week. I couldn't give you an idea of my complexion if I tried. It was the heavy artillery which gave me my first baptism of fire. For three hours we lay flat on the ground while the shells fell all around us. One of them burst scarcely more than five or six yards from me, making a great hole in the ground and covering me with earth and debris. But the worst thing about all this is the smell of the dead bodies. The other day my section was detailed to bury some thirty half-putrefied corpses. You cannot imagine what this work is. Oh what horrors I have witnessed, — terrible wounds and ruined villages. What brutes these Germans are to burn the farms. I am quite ready to give my life if I know that you will make the sacrifice of it for France. I feel that I am surrounded with prayers, and I often pray for you all. One of my best comrades here is a priest who is also a second lieutenant like myself. A thousand affectionate remembrances to all. God preserve us all as He has done so far. Your son and brother who sends warmest love.

September 12.

Here is a piece of news for you. I have been put in command of a company. I of course keep my old rank, but I have all the powers, rights, and also all the responsibilities of a captain. It's terrible. When I was told this yesterday, it really made me sick, thinking of the lives of all these men in my hands. Pray for me often. I need your prayers now more than ever. I feel so young and inexperienced. You have no idea of the horrors of a battle field. You cannot imagine it. This morning we went through a village where only a single house and the church had not been burnt. All the rest had been given over to the flames, nothing but the four walls standing. You should hear the inhabitants tell of the suffering they have gone through and see the houses where these German brutes have passed. The cannon are thundering, and we are continuing the pursuit of their fleeing army. On the ridge which I am holding they have abandoned a considerable quantity of artillery ammunition. Have you any news of the Londoners and of Marguerite?{3} I get nothing from you or England. I have had only a post card since I left Belley.

September 22-24 and 27.

I have been two weeks without taking off my shoes, washing or shaving. I am writing you under shell fire, and I eat and sleep in the same conditions. It is terrible the state of mind you get into on a battle field. I would never have believed that I could remain so indifferent in the presence of dead bodies. For us soldiers, human life seems to count for nothing. To think that one can laugh, like a crazy man, in the midst of it all. But as soon as you begin to reflect an extraordinary feeling takes possession of you, — an infinite gravity and melancholy. You live from day to day without thinking of the morrow, for you ask yourself, may there be a morrow? You never use the future tense without adding, If we get there. You form no projects for the time to come. Everything for the moment is at a standstill. What a strange life. You almost think you would prefer to know what is coming. And to think that God knows and that He had foreseen it all! A captain who is a friend of mine and who is a very pious Catholic, said to me the other day that before every battle he prays. Our major answered that it was not the moment for such things and that he would do better to attend to his military duties. The captain replied: “Major, that doesn't prevent me from commanding, taking orders, and fighting. On the contrary, it braces me up.” I said: “Captain, I do just as you do, and I too find that it does me good.” My dear little mother writes me that she would so like to press my weary head to her heart. And I too; for sometimes I am all done up, especially since I have had this company to command. To-day is Sunday, ten A.M. You are going downstairs to prayers, and papa will pray for “our soldiers and sailors.” Oh pray earnestly for them. How painful it is to hear the cannon roar on Sunday, instead of listening to songs of praise and prayers. I embrace you all most tenderly, my dear ones.

September 28.

It seems that the longer this war lasts, more the chance of escaping diminishes. But have confidence in our Heavenly Father. Nothing happens without His volition. It was predicted that this war would be either very short or very long.

October 4.

To-day for the first time since the war began, I have been able to take what resembles a bath and really get clean. I have a wonderful major, who knows his profession and in whom I have perfect confidence, which is an important thing. He pushes me ahead and says that he is going to make me a leader.

October 9.

I learned yesterday by the newspapers, of the death of Captain Valentin. It is heartrending. Poor Gambier. Such a charming fellow. And why all this? Oh, this cursed war. Poor Bolle. His right arm gone. But at least he escaped with his life. Yesterday, as we were back of the firing-line having our periodic rest, I took advantage of this and invited to lunch the commander of our battalion and a captain whom I like very much. We gave them a fine meal. Here is the menu: Entrée: sausage and ham, preceded by a delicious soup; a round of beef with a famous sauce, canned peas, which were most palatable; a roast with fried potatoes — I only wish I could send you some — browned to a golden yellow; salad, apple fritters, a tart, cakes, pears; wine: Bordeaux white Graves; coffee and chartreuse! The major nearly fell off of his chair at the sight of all this and of course we were highly complimented. And all this was done by my cook, a miner from Saint-Étienne, aided for the occasion by my landlady. In addition, we had a large white tablecloth, plates changed every second course, etc., etc. We didn't know ourselves with all these frills. It is odd how here at the front, for weeks at a time, we eat like pigs, and on the whole badly, when we suddenly start gormandizing and are idiotic. For instance, yesterday's lunch was simply an idiotic thing to do. But then you will admit that we might have done something worse. And now that I have got a bed, I can't get to sleep in it. How can you expect me to sleep undressed in a bed when I have got in the habit of sleeping with my boots on, with a revolver at my side, on straw? I have a letter from brave uncle Charles. You might think it written by a strategist. The brave old uncle is just dying from a desire to fight at my side. He writes that if he could do so, his only prayer would be not to die before he had killed, he himself, “at least three Boches! “

October 17.

Here is a true story that Papa might like to send to Le Progrès. For the past ten days we have been holding the little village of Gemainfaing, which the Germans bombard generously for several hours every day, without ever having wounded a single man in our battalion. One fine day, however, when the bombardment was worse than usual, they finally succeeded in wounding somebody, but he was a German! Here is how it happened. A shell fell on the house occupied by the commander of our battalion, broke through the roof into the haymow and burst there. None of the soldiers was hurt, but they were not a little surprised to suddenly see fall down from above among them a poor devil of a Boche who, since the enemy had left the place, had hidden himself in the hay, where he was nearly dead with hunger. The unlucky fellow, a reservist with nine children, was thus driven from his hiding-place by a German shell and was, in addition, wounded in the arm. Rolling down from the loft like Cyrano from the moon, he landed in spite of himself in the midst of a group of French troopers! He begged them not to kill him, whereupon they took him to the major, who gave him a cordial and sent him to the doctor. This is one of our best stories. But there are others which happen every now and then to enliven our existence.

If it were only that I wish to see you all, I would not complain at being disappointed in this respect. But what grates on my nerves is this separation which threatens to last indefinitely. Then I sometimes find myself asking myself the question, Shall we meet again? To be left in doubt on this point is excruciating; and yet it is better that it be so. But if it were only possible for God to reply to our prayers and let us see that His will agreed with our dearest wishes, what a c...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Translator’s Note

- PREFACE

- LETTERS FROM THE TRENCHES ON THE ALSATIAN FRONT

- L'ENVOI