eBook - ePub

A Narrative Of Personal Experiences & Impressions During A Residence On The Bosphorus Throughout The Crimean War

[Illustrated Edition]

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Narrative Of Personal Experiences & Impressions During A Residence On The Bosphorus Throughout The Crimean War

[Illustrated Edition]

About this book

[Illustrated with over two hundred and sixty maps, photos and portraits, of the battles, individuals and places involved in the Crimean War]

Lady Alicia Blackwood née Lambart, (1818 - 30 July 1913) was an English painter and nurse, married to the Rev. James Stevenson Blackwood.

As she recounts in A Narrative of Personal Experiences & Impressions during a Residence on the Bosphorus throughout the Crimean War (1881), Lady Alicia Blackwood and her husband "were deeply moved to go out" after hearing of "the battle of Inkerman, that terribly hard-fought struggle". Dr. Blackwood obtained a chaplaincy to the forces; Lady Alicia and two young women friends accompanied him, determined to find some way to help. Lady Alicia applied to Florence Nightingale at Scutari in Dec. 1854. Nightingale's opinion of ladies who came out to assist the hospitals was generally low, but she took to Lady Balckwood and she was delegated by Nightingale to create and manage an unofficial hospital for the wives, widows and children of soldiers in Scutari. In a letter of March 18, 1855, Nightingale disparagingly refers to the women and children as Allobroges, the shrieking camp followers of the ancient Gauls. In her account, Lady Alicia describes the horrific conditions under which she found them, "as much sinned against as sinning", and discusses the changes she was able to make for their relief as part of her work. Blackwood's respect for Nightingale and her work are evident throughout her account, which is both vivid and enjoyable to read.

Lady Alicia Blackwood née Lambart, (1818 - 30 July 1913) was an English painter and nurse, married to the Rev. James Stevenson Blackwood.

As she recounts in A Narrative of Personal Experiences & Impressions during a Residence on the Bosphorus throughout the Crimean War (1881), Lady Alicia Blackwood and her husband "were deeply moved to go out" after hearing of "the battle of Inkerman, that terribly hard-fought struggle". Dr. Blackwood obtained a chaplaincy to the forces; Lady Alicia and two young women friends accompanied him, determined to find some way to help. Lady Alicia applied to Florence Nightingale at Scutari in Dec. 1854. Nightingale's opinion of ladies who came out to assist the hospitals was generally low, but she took to Lady Balckwood and she was delegated by Nightingale to create and manage an unofficial hospital for the wives, widows and children of soldiers in Scutari. In a letter of March 18, 1855, Nightingale disparagingly refers to the women and children as Allobroges, the shrieking camp followers of the ancient Gauls. In her account, Lady Alicia describes the horrific conditions under which she found them, "as much sinned against as sinning", and discusses the changes she was able to make for their relief as part of her work. Blackwood's respect for Nightingale and her work are evident throughout her account, which is both vivid and enjoyable to read.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Narrative Of Personal Experiences & Impressions During A Residence On The Bosphorus Throughout The Crimean War by Lady Alicia Blackwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I.

Sultan, his death in 1880, and how it led me to think of writing out this narrative from my memorials – News of the battle of Inkerman and the sufferings of sick and wounded determines us to go to the seat of war – Arrived at Marseilles we embark in the ship "La Gange" with French troops on board – A gigantic Arab Marabout and his fourteen wives. – Our voyage calm, after a previous violent storm – Arrival off Constantinople late in the day – Unceremoniously obliged to leave the ship – Dark when we reach Galata pier – Unpleasant and perilous landing there – Help from a stray British sailor and a soldier – Deluge of rain and torrents of mud on the dreadful streets of Galata – Arrival at the gate closed by a Turkish guard – Our first acquaintance with the term "Bono Johnny" – Arrived at last at Messirie's hotel, to our great relief.

HAVING resided at Scutari throughout the period when the Bosphorus and its hospitals became of such deep and thrilling interest in connection with the Crimean War, I naturally made notes of such things as came under my personal observation, or occurred within my knowledge.

For many years these memorials lay undisturbed after our return to England, until my attention was attracted to them anew by the following circumstance:–

I had brought from Turkey a singularly docile and useful little horse, which had been named "Sultan" by my nephews in England. He had attained the age of at least thirty-four years, and was an object of interest to many friends until he died in 1880.

His death seemed to recall to memory the many scenes in which he had served me so usefully, and had become a sort of sharer in them.

Copious histories and numerous treatises have no doubt been written upon all the great matters of the Crimean campaign; my narrative makes no pretension to describe affairs so well known as are the peculiarities of that remarkable war. But many things unnoticed in larger works may yet be worth recording, and I trust that the true statements and anecdotes which I have been led to note may be found not to be without a special interest in their own kind. Therefore, without further prologue, I proceed.

When the news reached England of the battle of Inkerman, that terribly hard-fought struggle which took place on the 5th of November 1854, and wherein so many lost relatives and friends, and from whence came calls for help to the sick and wounded, my husband and I were deeply moved to go out; having at the time no special duty to detain us, it was far more trying to remain at home than to answer the appeal, and with willing hearts and hands to be ready to do whatever might be needed to the best of our abilities.

Finding, however, that we could be of very little service without a specific appointment which only could give admittance to the hospitals, Dr. Blackwood applied for and obtained a chaplaincy to the forces.

At that time two young Swedish ladies – Emma and Ebba Almroth – were staying with us, who, equally eager to be useful, at once expressed their wish to accompany us. In the preparations for the departure of so large a party, we were liberally assisted by many kind friends, especially Lady Ashtown and her sister Mrs. Gascoigne, Lady Maria Forester, Miss Michell, and others, who shared with us the same longing desire to help, but who were not at liberty to go out personally as we were.

So soon therefore as arrangements were made we set out to Paris and Lyons, thence, partly by steamer on the Rhone and partly by railway, we reached Marseilles on the third day. Now, the journey is more speedily accomplished, the railway going the whole distance; but at that time it was not so: the steamer on the Rhone made an agreeable variety to usual travellers, but it was a decided delay to those more intent on the rapidity which business requires than on pleasure making.

At Marseilles we learned that the first vessel sailing to Constantinople would be "La Gange," and that it would start the next afternoon with French troops, but that a passage in her could be secured for us, which was done.

Accordingly we embarked the following day, our party consisting of my husband and self, our two young Swedish friends, and a maid-servant, who promised to fulfil, and seemed capable of performing any duty that might be reasonably required of her.

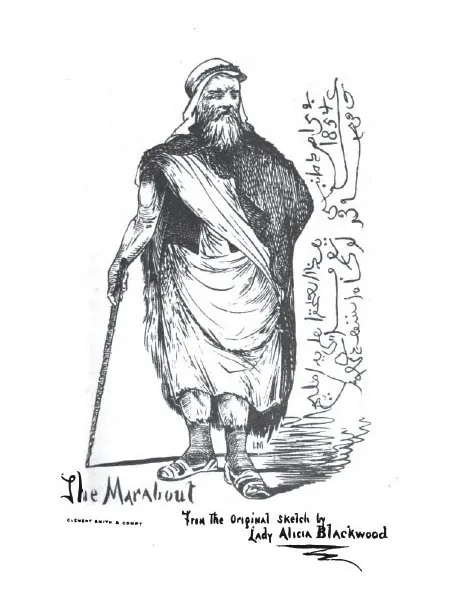

Amongst our compagnons de voyage were some eighteen or twenty Arabs, and as they kept to the distant part of the ship, we were not a little amused by watching them – nearer acquaintance might not have been so agreeable. The very perceptible chief of the party was a man of immense stature, three or four of the number were attendants, and the rest were women.

The gigantic form of the Marabout, for such he was, especially attracted our attention, and he appeared to be some one of note in his way. On inquiry we learned he was closely related to the well-known Abd-el-Kader, at that time a prisoner in France.

I could not refrain from making a sketch of this very picturesque person, though I did not intend he should see me; but his quick eye soon spied it out, and bringing an interpreter he approached, asking permission to look at what I was drawing.

I own to having felt a little shy at the request, not knowing how he might be affected by the gratification of his wish, for though he was the peeping intruder, perhaps I had no right to depict him. However, as he seemed more amused than angry, I at once handed him my sketch-book, at which he laughed heartily, and immediately offered to write his own name under his portrait, and the date of the performance.

This pleased me, and so for a short time we became as good friends as we could, through an interpreter, he not speaking French sufficiently to be understood. Notwithstanding the friendship, however, he obviously despised us as much beneath him, because, forsooth, he had fourteen wives, to whom he pointed, while he hinted that my husband had but three, and only one attendant!

Honestly, I could not regret that, shortly after this, the effect of an increasingly rolling sea parted us, and we saw no more of him, his attendants, or his wives, until we reached Constantinople.

Here I desire to record the goodness and loving-kindness of our heavenly Father, and to bear grateful testimony to the faithful fulfilment of His promise, through Christ, "If two of you shall agree on earth as touching anything that they shall ask, it shall be done for them of my Father which is in heaven."

Now it so happened that one of our party having some little time previously experienced a frightful storm with great danger in crossing from Antwerp to London, was henceforth timid at sea, and felt rather nervous at the prospect of seven days' sail in the Mediterranean during the winter. Before setting out, therefore, on this undertaking, some friends met together, and in the exercise of faith on the Saviour's promise, besought Him to hear their petitions which were for three things: First, that it might please Him to remove all fear for the voyage, granting us a happy and calm transit to our destination; secondly, that a sphere of usefulness might open to us on our arrival; and thirdly, that health might be 'granted to enable us to fulfil the same. The sequel will show how perfectly every request was fulfilled, and that in a manner and through circumstances impossible to be foreseen, and over which therefore we had no control.

First, then, an unexpected and "unpreventable" occurrence detained us from starting at the time we intended, and we were delayed for about a week, during which time a heavy and dangerous storm passed over the Mediterranean. When we steamed off from Marseilles we felt but the mere swell of it for a while; the voyage was in all respects a most agreeable one, the weather lovely overhead the whole time, enabling us to enjoy the sights of the coast by which we sailed in threading the islands of the Archipelago, and giving us finally that splendid view of Constantinople as you approach the city from the Sea of Marmora, which has been so much and justly applauded.

Strange to say, we had no sooner arrived off Seraglio Point, opposite Galata, than the clouds gathered darkly around us, and rain began to fall with the early closing of daylight.

It was on the 18th of December, about four o'clock in the evening that "La Gange" came to an anchor, and, alas for us! strict orders were given that all passengers should leave the ship before night.

It happens there, as it does in most places where the sea is confined in narrow bounds, if a sudden storm arises, it swells, and boils, tossing to and fro, making it very dangerous for boats or small craft venturing on it. Thus it was now with us, consequently none came to take us on shore until late in the evening. A small boat, with one man to row, was all we could get, and into which Dr. Blackwood, our two Swedes, myself, and servant stepped; it was now quite dark and the rain falling in torrents. Trusting to that Almighty hand which had hitherto protected us, for we could almost say "not knowing whither we went," we arrived at the side of what in those days was called Galata pier.

And here our difficulties began. I am told that since that time, now nearly twenty-seven years ago, all things are wonderfully changed at Constantinople, and in the foreign Bradshaw you may read of a railway station, omnibuses to take you to the different hotels, or cabs even for hire. Such improvements I can as little picture to myself, as any one who has not landed at the port of an Eastern shore, or who did not see Galata itself in those days, can imagine what its pier and the surroundings of its pier were.

A few broken planks resting on tumbledown posts, barely keeping one's feet from the green filth which floated beneath; an accumulation of every abominable and putrid thing which the waves tossed up and down, yet with no tide to carry away, and beyond the reach of the current.

This was our landing-place. What next? First, a perfect Babel of tongues greeted us, Turks, Greeks, Armenians, – all shouting together; then darkness overshadowed us; and this would have been complete, but for the few oiled-paper lamps held by some of the crowd, most of whom were eager to steal your bags and portmanteaus, or cloaks, or anything which was to be had, and unscrupulously ready to murder you if occasion needed, or permitted, in order to obtain the desired prize; and rain all the while pouring down in pitiless torrents. Here, as I said, our difficulties began, and seemed indeed overwhelming. What were we to do? who could understand us? who would direct us to the nearest hotel? was any conveyance to be had? if so, how? All these questions ran through our minds far more quickly than they could be expressed! Such things as conveyances, however, belong to civilised nations of the present day; they did not belong to Galata in those times! But we were not left nor forsaken; the kind Providence which had hitherto guided us sent help at the moment we so needed it. Just as we exclaimed in an almost despairing unbelief, "What shall we do?" the boat being now fastened to one of the crazy posts, a good broad Scotch voice was heard above the almost deafening din –

"Sir, will you let me have your boat? I'm a sailor, sir, on board the 'London,' and I'll be miserable to be here all night."

The name "London" immediately caught my ear. "It is my nephew's ship," I said, "and he would help us at once."

Dr. Blackwood replied, "The boat is not ours, we have but hired it to bring us from 'La Gange,' in which we have just arrived; but see in what distress we are. My good man, you must help us. We do not know which way to turn, or who to speak to. Pray tell us how can we find Messirie's Hotel in Pera; do, therefore, help us, and do not leave us to the mercy of this rabble in such a night and in such a place."

"Well, sir, I don't know the way, but at any rate, if you are there with ladies, I'll do my best. This is no place for ladies; it's bad enough for any one, but ladies can't stay here."

He helped us accordingly to land, trying to keep us upon the wretched planks which were full of holes and tipping up and down, some of them with spaces large enough between to allow us to fall through into the mire beneath.

"Does any one here speak English?" he shouted, and just then one of the crowd holding a paper lantern turned it accidentally upon the scarlet uniform of a British soldier, who came up offering assistance, for our dilemma was manifest. We accepted it, and said if he and the sailor would protect us, we would thankfully place ourselves under their care.

"Very good, sir," said the soldier. So he and the sailor collected our bags and such things as we had, seized upon a couple of Greeks, and made them carry the luggage and a lantern (for there was no light there but what was in the hand), and on we marched, the sailor in front, the soldier behind, the porters immediately in front of him.

Thus escorted we felt pretty safe, for "where ignorance is bliss 'tis folly to be wise," we are told; so on we marched, stumbling however continually. Pavement there was none; in lieu of which luxury the streets had great stones rolled into them of all shapes and sizes, as though they had been thrown out of a cart and left to fix their own abode wherever they listed; in daylight they kindly kept us from pools of mud, by our carefully selecting their tops for our stepping places; but in the present instance, being dark, we as often slipped from them into mire as not.

On we went, however, and on we went, for the rugged road seemed to us interminable. At length we came to some horrible-looking khan or inn, where our first escort suggested we might possibly find lodgings for the night, as neither he nor the soldier knew anything of Messirie's Hotel, nor its direction. In our ignorance of Turkish hotels or khans, therefore, we opened the door and peeped in, but somewhat cautiously and suspiciously. A ruffian-looking pair advanced towards us, while others equally repulsive were seated round a brazier with...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I.

- CHAPTER II.

- CHAPTER III.

- CHAPTER IV.

- CHAPTER V.

- CHAPTER VI.

- CHAPTER VII.

- CHAPTER VIII.

- CHAPTER IX.

- CHAPTER X.

- CHAPTER XI.

- CHAPTER XII.

- CHAPTER XIII.

- CHAPTER XIV.

- CHAPTER XV.

- CHAPTER XVI.

- CHAPTER XVII.

- CHAPTER XVIII.

- CHAPTER XIX.

- CHAPTER XXI.

- CHAPTER XXII.

- APPENDIX.

- Crimean War Images