eBook - ePub

Connecticut River Shipbuilding

Wick Griswold, Ruth Major

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Connecticut River Shipbuilding

Wick Griswold, Ruth Major

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Shipbuilding and shipping have always been key elements in the life of Essex. Since the seventeenth century, the men and women of the lower Connecticut River Valley sustained maritime traditions that spanned the globe in splendid wooden sailing vessels. Their accomplishments include building the first warship of the Connecticut navy and the world's first submarine. They also served as packet ship captains, navigators and skilled crew members who crossed the Atlantic. The Essex area was also home to dedicated craftsmen who produced some of the finest yachts ever built. Noted historians Wick Griswold and Ruth Major detail one village's important role in American maritime history.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Connecticut River Shipbuilding an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Connecticut River Shipbuilding by Wick Griswold, Ruth Major in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Marine Transportation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Dauntless No. 1

If there is one name that is most significantly associated with Essex boating in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that name would be Dauntless. Today, the Dauntless Shipyard stands at the head of Middle Cove. The fabled Dauntless Club enjoys its view of the river down on Novelty Lane. It is the current occupant of the legendary Hayden House, harking back to the town’s earliest shipbuilders. There are three boats that have carried the name Dauntless on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Each of them has an important place in American maritime history and the legends of Essex.

The vessel that lent its name to other boats and a club that followed in its wake was, surprisingly, not built in Essex, although most folks think it was. The original Dauntless was designed by J.B. Van Deusen and built by the Forsyth and Morgan yard in Mystic, Connecticut. Originally rigged as a sloop in 1866, as the cloud of the Civil War was finally lifting from the country, it was initially named L’Hirondelle and owned briefly by S. Dexter Bradford. In 1867, it was lengthened to 121 feet and rigged as a schooner. It grossed 299 tons and had a 25-foot beam. The new owner was the larger-than-life newspaper czar James Gordon Bennett. He changed the name to Dauntless, a name that still resonates on the Connecticut River and beyond.

Bennett was to become the commodore of the New York Yacht Club and raced his beautiful schooner in British waters for several campaigns. His nickname in club circles was the “Mad Commodore,” and he did his best to live up to the title. He was an avid sportsman; polo and ballooning were among his pastimes. He was also a dedicated tennis player. Bennett was notoriously bibulous and once caused the end of an engagement when he proceeded to relieve himself in the fireplace of in-laws-to-be during an elegant New Year’s Eve soiree. The brother of the affronted and embarrassed fiancée gave him a sound thrashing with a horsewhip. The unrepentant Bennett then challenged his never-to-be-brother-in-law to a duel. Fortunately, they were both such lousy marksmen that they escaped unscathed from the confrontation—and wound up coming to an uneasy truce over a few beers after their near misses.

Prior to his acquisition of the Dauntless, Bennett was the winner of the first transatlantic yacht race. On a bet that grew out of a brandy-soaked evening at the Union Club, the young newspaper scion and two of his partners in revelry agreed to match their schooners against one another across the North Atlantic in December 1866. Although his boat, the Henriette, was the oldest and slowest of the three, the brilliant seamanship of Bennett’s captain, an old packet skipper named Sam Samuels, gave him the win. It established Bennett as the world’s premier yachtsman. He was feted by Queen Victoria and the cream of British nobility. The only downside to the race were the six crewmen who were swept overboard from one of the losing schooners. Such were the perils of a common seaman’s life. The names of drowned men were lost to history, until a diligent researcher uncovered them in the twenty-first century.

Bennett swapped out Henriette for Dauntless and continued to follow his passion for long-distance yacht racing. In 1870, he raced Dauntless in a transatlantic match against Sir James Ashbury’s schooner Cambria from Daunt Rock off Cork, Ireland, to Sandy Hook, New York. Dauntless unexpectedly lost that race, due to some questionable tactical decisions. But it didn’t lose by much. That east–west ocean duel lasted twenty-three days, and Bennett’s boat tailed the English yacht to the finish line by less than two hours. By then, Dauntless was the flagship of the New York Yacht Club Fleet. It would continue to race across the Atlantic and compete in both English and American waters. Bennett eventually sold Dauntless to John Waller, who owned it for only three years.

In 1882, Caldwell Hart Colt, the son of Samuel Colt, the inventor who created the revolving pistol, purchased the Dauntless from Waller. It was the young Colt who eventually brought the lovely schooner to Essex, where it found its true home. Known to his many friends as “Collie,” Caldwell Colt is one of the most interesting figures of the nineteenth-century American yachting scene. His active, short life was (like many sons of successful Gilded Age men) filled with languor, luxury, boats, drink, decadence and, ultimately, disaster. Collie Colt was heir to a vast fortune, a famous name and an industrial empire. But sadly, he also was an unwitting victim of what has come to be known as the “Curse of the Colts.” His family, though it had aspects of great wealth, honor, accomplishment and glory, also had much more than its share of terrible tragedy.

This curse was transmitted to Caldwell though his father, Samuel. Sam’s mother died of tuberculosis when the boy was only six. His father remarried and sired three half sisters for Sam and his brother. One of the girls died in infancy, one died as a teenager and the one who survived committed suicide. There was a lot of death and change for a sensitive, smart boy to handle. And young Samuel had his share of emotional ups and downs as he passed from childhood into his teenage years. He began to work in his father’s textile mill, but it was decided that he should further his education.

Sam was admitted to Amherst Academy in Massachusetts. The prep school was selected so that he might study navigation, since from early in life he had a fascination with the sea. Unfortunately, he was tossed out of the school. The main reasons for his dismissal were inattention to his studies and poor grades. At his father’s insistence, he then shipped out as an ordinary seaman aboard a ship named the Corvo. During his long watches on deck, his mechanically oriented mind became fascinated with the way the ship’s wheel was geared. This fascination led him to put together the rudimentary ideas that ultimately evolved into the revolving mechanism that became the Colt .45.

The family’s tragic vector cast a shadow over the life and fate of Sam’s brother, John. John was a colorful character to say the least. He was a noted womanizer and ne’er-do-well. He was a notorious riverboat gambler, a fur trader, a soap salesman and a farmer. At one point, he was the debate coach for the University of Vermont. He finally found his niche as a traveling lecturer. John’s favorite topic was double-entry bookkeeping. He wrote a textbook on the subject that was popular and profitable. Sam was hopeful that his wild brother had finally settled down, but such was not to be the case.

To Sam and his family’s horror, John committed a grisly murder. The deranged Colt brother hacked a printer named Samuel Adams, who had printed his book, to death with a hatchet. The reason was a dispute over $1.35 discrepancy in the payment of a bill. John packed the corpse in a shipping crate that he ticketed for New Orleans from the port of New York. The rotting mess was found in the hold of the ship Kalamazoo before it left the dock. Detectives began to work backward to try to solve what could only be called a horrific crime.

John Colt was summarily charged and arrested. He was deemed sane enough to stand trial, although “insanity runs in my family” was a drumbeat during the trial. Throughout the court proceedings, Sam was in attendance almost every day and picked up his murderous sibling’s legal fees. Sam saw to it that his brother lived as luxuriously as possible while he was imprisoned in the Tombs. Catered meals, cigars, plush carpet and a real bed were the order of the day in his cell. Needless to say, the New York and national press had a field day with such a high-profile case. Ironically, James Gordon Bennett Sr., father of the Dauntless’s future owner, led the charge to excoriate the murderer.

The Colt family black sheep was found guilty of first-degree murder. He immediately began the appeal process, but it was to no avail. His death sentence remained in place. But even that event, which should have been routine, was fraught with drama and intrigue. Attempts to smuggle him out of jail dressed as a woman failed. Hours before he was to hang, he married Caroline Henshaw, a pregnant Scottish woman. Rumor had it that the fetus she was carrying was really Sam’s, not John’s. After the wedding ceremony, a fire broke out in the Tombs. When the confusion settled down, John was found dead from a self-inflicted stab wound. It is believed that a family member slipped him a folding knife during the wedding. For years, conspiracy theorists surmised that John Colt did not die that day, but no proof of that was ever found. Suffice it to say, it was a terrible chapter in the annals of a family that had more than its share of tragedy.

Samuel Colt, the man who changed the social order of America with his Peacemakers, continued to have cascades of ill fortune heaped upon himself and his family. After some rocky starts, his enterprises became wildly successful. He reaped an extraordinary amount of honors and riches. But they were not to buy him happiness. He married Elizabeth Jarvis Hart in 1856. They had three children together, but only one, Caldwell, would live to reach adulthood. During the first year of the Civil War, which added to his estate immensely, Sam Colt died of gout-related complications. He left a pregnant widow and their three-year-old son, Caldwell Hart Colt. The baby Elizabeth was carrying was stillborn, and little Caldwell became the only-child center of her world.

Elizabeth was a doting mother, for sure, but she was also a shrewd businesswoman. She guided the Colt industrial empire with a firm hand and an agile mind. The Connecticut-based company continued to flourish and grow on her watch. In his twenties, Caldwell was named vice president of Colt Manufacturing. It was Elizabeth’s fervent wish that he would lead the enterprise and fulfill the destinies and dreams of his father. The Yale-educated young Colt initially showed promise. At the tender age of twenty-one, he invented a double-barreled repeating rifle. Only sixty-five of the .45-70 Government–caliber weapons were made, which he distributed to friends. They are among the rarest and most valuable of Colt firearms today. But alas, to the concern and consternation of poor Elizabeth, Caldwell’s path was not to be one of corporate ascendency. He preferred the profligate life of a scion of privilege, in the fashion of James Gordon Bennett Jr.

Yachting, fishing, hunting, strong drink, fine food and attractive women were the axis around which Caldwell’s world spun. Central among these were boats. He owned five yachts in his lifetime. He spent millions (in today’s dollars) on them. His devotion kept him on the water for an average of ten months each year. Of all the beautiful boats he owned, though, the Dauntless was the one closest to his heart. He took his mother across the Atlantic on it in 1882, and they proceeded to do their version of the Grand Tour. Mother and son scooped up European treasures and brought them back to Hartford to grace the expansive rooms of Armsmear, the grand family residence. Many of these artistic treasures may now be found in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford’s venerable world-class art museum.

Like Bennett, Caldwell also raced the Dauntless across the Western Ocean; in what has been called “an almost suicidal attempt to defeat the Coronet,” Colt buckoed his crew like a clipper ship driver. He urged them on day and night through tempest after tempest. Owner Caldwell resisted the advice of his captain, Sam “Bully” Samuels, and sailed the sleek schooner into the teeth and eye of a hurricane. The boat was severely damaged. Crewmen had to man the pumps constantly to stay ahead of the leaks. Damage to the water tanks caused them to run out of fresh water. On a boat, in the middle of the ocean, that can be a circumstance that can often prove fatal. The resilient Commodore Caldwell responded to the dilemma by rationing champagne, ale and wine to keep his crew hydrated. The race was lost, but the crew wound up with a great sea story to tell around the yacht club bar. Colt was out $10,000, but it hardly mattered to him. He was doing what he loved. He was soon to become vice (no pun intended) commodore of the New York Yacht Club.

The schooner Coronet was owned by Rufus T. Bush, an industrialist and an oil refiner. His testimony against Standard Oil for its monopolistic railroad practices raised many eyebrows among his robber baron cronies. But Bush didn’t care. He had a transatlantic race to win. His triumph was celebrated on the front page of the New York Times. After his victory over Colt, he sailed his splendid schooner around the world. The Coronet was then passed on to a series of owners, including the Kingdom, a secretive, cultish religious sect. The Kingdom owned it from 1905 to 1995 and sailed around the world on “prayer missions” and proselytizing voyages. One of these, to Palestine, ended in tragedy when six people aboard died of scurvy. The group’s demented leader, Frank Sandford, was convicted of manslaughter as a result. Eventually, the International Yacht Restoration School acquired Coronet and commenced a complete rebuild and restoration. It survives to this day and can be seen docked on Thames Street in Newport, Rhode Island.

As he entered his thirties, Caldwell settled into a routine based on sailing the waters of Florida in the winter, cruising the Atlantic coast in the summer and bringing the Dauntless to Essex every autumn to take advantage of the excellent duck and rail hunting on the Connecticut River estuary. Every year between 1882 and 1894, the return of Colt and the Dauntless was an annual event that marked the changing of the seasons and the beginning of a serious social swirl in town. Caldwell would anchor his schooner in the deep water off Ely’s Ferry Wharf. The playboy yachtsman would lavishly entertain his Hartford and New York friends over copious drinks and game dinners and raucous conviviality. Flares and lanterns were set in the rigging, and cannons and rifles would boom and bark. A makeshift band composed of his sailors played popular tunes, and the revelries would go on until dawn. As the days shortened and the chilly winds blew down the river, Colt would point his prized sailing yacht south and follow the birds to continue his pattern of hunting, fishing and pleasure-seeking in warmer waters.

It was there, off the coast of Punta Gorda, Florida, that the thirty-five-year-old bon vivant met his enigmatic end, fulfilling the prophecy of the “Curse of the Colts.” Everyone at the time agreed that he died aboard his boat. The manner of his death, however, continues to be a matter of mystery, conjecture and controversy. Was it tonsillitis? Chicken pox? Cirrhosis? Did he fall overboard while drink taken? The most persistent answer to this riddle is that the unabashed rake was shot to death by a jealous husband. In many ways, this, even if it is not the case, is the most satisfying answer. It puts a period to the end of a life that is rife with irony. This would especially be the case if the cuckolded pistolero was using a Colt revolver. In any case, Caldwell Colt was dead at the age of thirty-five, leaving Elizabeth to mourn yet another untimely demise.

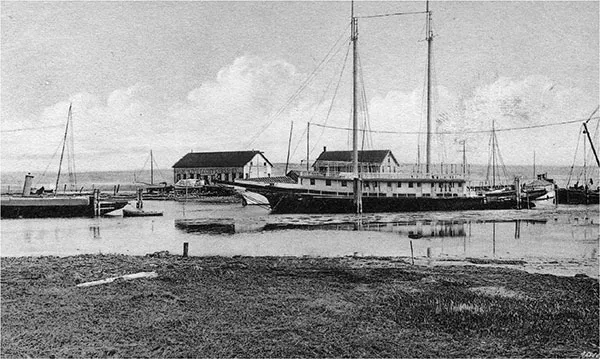

Caldwell Colt’s schooner Dauntless decked over as a houseboat. Courtesy of Essex Historical Society.

After Caldwell’s death, his mother turned the Dauntless into an Essex-based shrine to her son. She insisted that the schooner be kept “shipshape and Bristol fashion.” Once a year, Elizabeth would come down from Hartford on the train and spend a week aboard the schooner to mourn her son and pray for his soul. She realized that as well made as the vessel was, its wooden construction rendered it somewhat ephemeral. To establish a more permanent edifice to memorialize her sailor son, Elizabeth erected a parish house at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Hartford. Earlier, she had the church constructed out of Portland Brownstone shipped up the Connecticut River on barges. It was built to perpetuate the memory of her husband and her deceased young children. She built it so her employees and their families would have a convenient place to worship and celebrate life’s important transformations.

Elizabeth commissioned the parish house to be constructed adjacent to the church to honor her son’s life and his love of the sea. The edifice still exists, and it is truly a remarkable monument to aptly celebrate Caldwell’s yachting life. The exterior of the building has images of the Dauntless carved into its stonework, along with Poseidon, seashells, billowing waves and other maritime imagery. The interior was fashioned to reflect the below decks of Caldwell’s yacht. Enshrined there are its ship’s bell and other pieces of equipment. One has the feeling that they are below decks on the Dauntless. A large portrait of Collie dominates the main hall. He stands purposefully at the helm, eyes fixed on the horizon…his course set toward eternity.

Upon Elizabeth’s death in 1902, the Dauntless was willed to one of her relatives on the condition that the schooner would never sail again. Permanently docked in Essex, it was leased to a New York sportsman to serve as a hunting lodge a for a few weeks a year. It was transformed into a houseboat and became a mainstay of the town’s picturesque waterfront. In the winter of 1915, the valiant ocean campaigner, now sadly neglected, sank at its moorings into the cold, murky depths of the Connecticut River. The legendary Captain Thomas Scott, builder of the Race Rock Lighthouse, was tasked with raising it and towed the once-proud racer down Long Island Sound to his boat yard, where it was broken up, put on a train and shipped to Wisconsin for firewood. Dauntless no longer dominated the Essex waterfront, but its legend and name became an ongoing part of the elegant town’s legend and lore.

The days of Colt’s Dauntless in Essex were a time of transition in the construction of vessels on the Connecticut River. As the Age of Sail came to an end, many of the larger shipbuilding facilities quietly closed. A few steamers were built, but the Saybrook Bar at the mouth of the river limited their size and drafts. As shipbuilding declined, prime waterfront areas opened up, and local craftsmen realigned their focus from creating world-spanning ships to building pleasure and utilitarian boats. Boatbuilding could be a dicey economic proposition, but it also afforded individuals the opportunity to become their own bosses. A few of the shipyards metamorphosed into boatyards. The Mack yard, which had become W. Frank Harrison’s boatyard, located at the head of the creek in North Cove, was purchased by Charles A. Goodwin, a prominent Hartford attorney, and renamed the Dauntless Shipyard, taking its name from Collie’s fable schooner.

Dauntless Shipyard

The Dauntless Shipyard was an important nexus in the transition from the glorious era of the grand sailing ships to the yachting mecca into which Essex would morph. Under the direction of Ernest N. Way, the shipyard responded to the challenges created by that transition. A brochure noted that “in the 1890’s there was a fierce competition among boat builders to design and build boats that were pleasing to the eye and fast sailers. As a result, some of the most graceful boats were built during that period. Aesthetics and skill were not the only important qualities: fast performance was a major factor as well.”

In 1894, Way responded to that challenge. He built several Chic-class day sailers. Designed by Charles Mower, they were twelve-by-nine-foot cedar-on-oak beauties...