![]()

XIV — AKRAGAS{33}

‘LOVER of splendour, fairest of mortal cities, home of Persephone, thou that inhabitest the hill of noble dwellings, above the banks where feed the sheep beside the stream of Akragas’—so Pindar addresses the place made famous already by Phalaris, but still more famous by Theron.

Not one of the noble dwellings seen by Pindar stands today, and of the temples that we now admire only one, the Herakleion, had been built when this twelfth Pythian Ode was written to celebrate the victory of Midas in the contest of flute-playing. We must realize, therefore, that this exquisite place, more Grecian as we see it than anything in Greece except incomparable Delphi, would be very different from what Pindar saw, even if all the southern temples stood complete and undamaged.

From the delightful garden of the Hôtel des Temples, fragrant with flowers unknown to the ancient world, we may look up to the hill of the acropolis and see it thickly studded with buildings just as it was five hundred years before Christ. The kindly distance may even conceal the fact that they are not all really ‘noble’. But as we look southward the eye ranges over green fields and orchards almost uninterruptedly for half a mile, to where the honey-coloured columns of three majestic ruins crown the ridge midway between us and the vivid African sea. In the sixth century this whole area was sparsely dotted with buildings, and in the fifth it was a populous quarter inhabited by many thousand people, amongst whom were some of the richest and most luxurious merchants of Sicily.

It is significant that Pindar speaks of Akragas as ‘the hill’. In his day the principal part of the city must still have been in the acropolis, but it is apparently an error to suppose, as most historians have, supposed, that there were no buildings outside this until the time of Theron. Freeman, who held this view, supported it very ably and convincingly by the analogy of Syracuse, which grew, as we have seen, by regular stages from the nucleus of the island of Ortygia. But the recent studies of Dr. Marconi,{34} who has been excavating and examining the walls and temples of Akragas, seem to demonstrate that the whole immense circuit of the walls was laid out in a single period, and that this period was earlier than 550 B.C. If his view is correct, then we must suppose that Akragas did not extend its bounds like Syracuse when it had to meet the necessities of a growing population, but was planned by its founders with a clear vision of its future development. Historical examples can be cited for each of the two types of town-planning. Athens, Rome, London, Paris, have grown like trees by adding periodical rings. But in our colonies and in the New World cities have often been laid out on a foreordained plan, within prescribed limits which it took many years to fill. Such was the case with Akragas, according to the view of the latest authority.

The official founders, who came from Gela in 580 B.C., and were reinforced by a contingent from Rhodes, had the advantage of planting their colony in a place that had already been very fully studied and surveyed. There is considerable evidence to prove that they were by no means the first Greeks to visit and appreciate a site which possessed so many natural advantages, and promised extraordinary opportunities for trade. The very rapid growth of the new settlement justified the wisdom of their choice. In less than a hundred years it had become a most notable city. Phalaris in the sixth century was undoubtedly a very powerful ruler; and by the beginning of the fifth century the ruler of Akragas was lord also of Himera, and controlled a territory which reached as far as the modern Licata on the east and Herakleia Minoa on the west.

Akragas derived its wealth principally from agriculture and commerce. In particular, as Diodorus states, it carried on a thriving trade with North Africa, which is only a hundred miles away. ‘No country produced finer or more extensive vineyards. Almost the whole territory was planted with olives, of which the finest were exported and sold at Carthage, as Libya was not cultivated at that time. The Akragantines receiving money in exchange for their natural products piled up immense riches.’

If the archaeological history of the sixth century is dim in comparison with that which follows upon it, yet it is being gradually elucidated by Marconi’s studies. Archaic temples, ornamented like those of Syracuse and Gela in the same century with architectural features of coloured terracotta, have been discovered at several points—all outside the acropolis. There was one close to the present church of S. Biagio, and two or three others on the line of the great southern wall where the more famous temples that still exist were afterwards erected by Theron and his successors. Primitive altars have been found in several places, intended as their form and accompaniments show for the special worship of the gods of the underworld. Two such altars stood by the temple of Demeter on the site of S. Biagio, and there are others between the great piscina and the temple of Castor and Pollux. But to the sixth century I shall devote no special attention in this short essay, preferring to concentrate upon that brilliant period of less than ninety years which separates Pindar from the Carthaginian siege.

From the accession of Theron in 488 B.C. to the sack by the Carthaginians in 406 B.C. is the time of the great glory of Akragas. After its destruction it was refounded like so many other Sicilian cities by Timoleon and recovered enough of its strength to be a formidable enemy to Agathokles. In the Punic wars Akragas played an important part, but after its ultimate capture by the Romans it shrank to the proportions of a small country town. Roman Agrigentum, of which the name has now been officially restored in place of the corrupt medieval name Girgenti, was perhaps less insignificant than is generally supposed, but certainly filled no place of any importance in history. Under the Saracens and Normans, however, the town received a new impulse and became for a while almost a rival of Palermo.

Our exploration of Girgenti—it is almost irresistible to use the name that is associated with so many literary memories—may well begin at the Hotel des Temples. In the hour before sunset that still remains after the arrival of the train from Syracuse or Palermo, let us walk out for half a mile along the level to the simple little Norman church of S. Biagio. Standing here and looking up, we see a long ridge just above us running east and west parallel to the sea, but distant more than two miles from it. This ridge parts into two distinct hills, each more than a thousand feet above sea-level. The nearer of the two is called the Rupe Atenea, the rock of Athena; the farther, separated from it by a narrow saddle, is occupied by the modern town.

It was on the further of these two hills that the Acropolis used to stand. West of the Acropolis the torrent known in ancient days as the Hypsas cuts its way through a deep ravine to the sea. Just beyond S. Biagio is the ravine of the other torrent, the Akragas, which forms the eastern defence of the great city. The ancient walls follow all the natural contours and indentations of the cliffs which bound the inner line of these two torrents until, about a mile from the sea, a strongly-marked ridge of rock runs due east and west before the land slopes finally down to the shore. The ridge was the basis of the southern wall, along the line of which are ranged the famous temples of the fifth century.

San Biagio is a small Norman church which has been built precisely over the space occupied by a little Greek temple of the simplest form. It stands on the side of a hill which is so steep that to obtain a level platform it was necessary to cut away the rock on the northern side, and to build a substantial wall of support on the south. A Greek road approaches the temple from the west, on the side from which we entered. The ancient building consisted of a cella or plain oblong chamber a little less than 20 metres long, with a vestibule or pronaos 10 30 metres long. All the vestibule and a part of the cella can still be seen outside the apse of the church. At the eastern end the vestibule must once have been bounded by two columns, but these have disappeared. Fragmentary remains of the roof show that it was made of terracotta tiles. The stone trabeation was brilliantly coloured in red and dark blue. Drainpipes, or gargoyles if we may so call them, for carrying off the water, were in the form of a lion’s head.{35}

This little temple is dated by the details of its construction to the early part of the fifth century, or more precisely to the years 480–470 B.C. It has sometimes been suggested that it was dedicated to the river god Akragas whose stream flows just below, but there seems little doubt that it marks a place sacred to Demeter and Persephone and consecrated to their cult. Instead of the rectangular altar which normally stands on the east side of any temple there are two round altars on the northern side. The cavity in one of them was found full of those peculiar terracotta vases called kernoi, which are known as the vessels of the ritual of Demeter. Numerous fragments of terracotta busts representing the two goddesses were also found in two caverns near by, which covered a sacred spring and had been the resort of Siculan worshippers even before the Greeks made their settlement. An ornamental portico was built in front of the caverns by the Greeks, who continued to worship and make their offerings at a spot which had been holy since time immemorial.

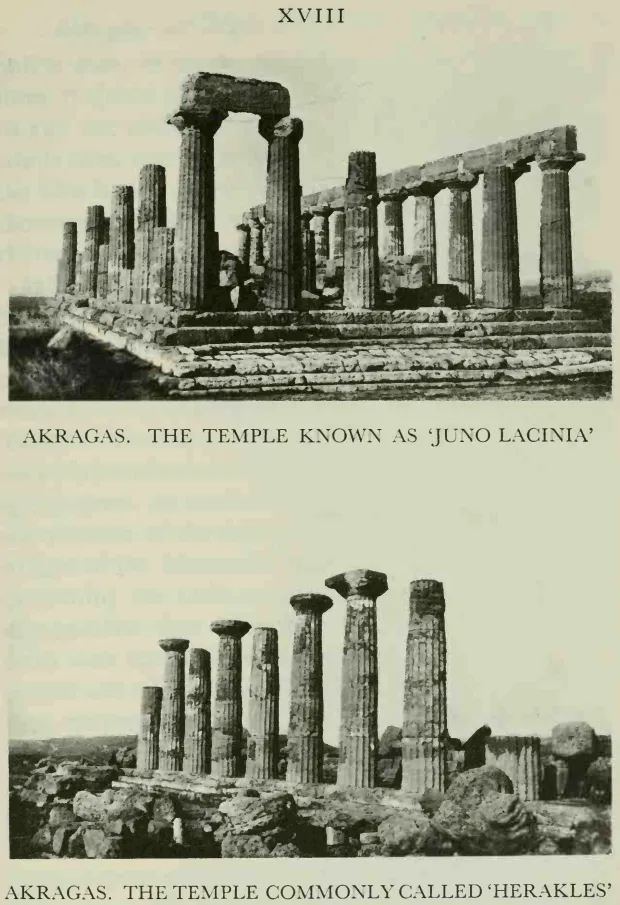

The line of the sixth-century fortifications can be clearly traced between S. Biagio and the temple of ‘Juno Lacinia’—a ridiculous nickname which has to be retained for purposes of identification. Just south of S. Biagio is a gate, which may be called for convenience the ‘first’ gate. Half-way between the first gate and the temple of Juno Lacinia is the second gate, defending the road from Gela. The whole system of the defensive wall surrounding Akragas is exceedingly simple in character; it is a plain curtain without bastions, towers, or engineering subtleties of any kind. Everywhere it is adapted to the natural lines of the ground, following the top of each ridge and incorporating any rocks or projections which saved the trouble of artificial building. Consequently it winds in and out with a very irregular outline, which is especially noticeable on the west side of the city. Only in one or two cases, where a lateral ravine makes a re-entrant angle, the vulnerable point is protected by an extra and more intricate piece of building; there is one instance of this at the gate of Gela and another on the western side at the gate of Herakleia.

It is most convenient to return from S. Biagio to the main carriage road, and to follow this as it winds down hill to the ridge crowned by the great temples. This road pierces the southern line of fortifications at the ‘Porta Aurea’ beside the temple of Herakles. A similar road led from the citadel to this gate in ancient days and formed the main artery of communication. It was met at various points by crossroads leading to each of the principal gates. The area immediately inside the Porta Aurea was occupied by the Agora, this much is virtually certain. But we must abandon all expectation of ever knowing the arrangement of the other public and private buildings within the vast expanse of the lower town, the space is too large and is too deeply covered with accumulated soil to permit of useful excavations. It may be surmised that the broken nature of the ground led to the formation of more or less separate quarters, perhaps a congeries of almost distinct villages, amongst which the wealthier citizens had those spacious dwellings of which not the slightest trace now remains.

Immediately east of the Porta Aurea is the Temple of Herakles, the earliest of that stately row of buildings which still lines the southern wall. Until a few years ago it was nothing but a tumbled mass of stones, but now, thanks to the restoration carried out by Government officials with the generous aid of Captain Hard-castle, R.E., we can form a good idea of its original appearance. It was an exceptionally long building of peripteral form, measuring over 73 metres in length by 27½ in width. On each side were fifteen columns, and at each end was a front of six columns with capitals of early Doric style. The cella, or sanctuary, itself was 47½ metres long, with a vestibule—if we may so call it for brevity—at each end. These vestibules, of which the eastern is properly termed the ‘pronaos’, and the western—which served as a treasury—the ‘opisthodomos’, were each enclosed by prolongations of the side walls. This produced the scheme technically called ‘in antis’, with two columns defining each open end. The date of the building is generally ascribed to the last years of the sixth century.

Whether the cella in this instance was roofed or not is a doubtful question which has not been positively decided. It is complicated by the occurrence of two distinct series of trabeation, of different dates and sizes, as to the original arrangement of which the authorities are not in agreement. There are traces of fire on many of the stones, probably from the sack and burning of 406 B.C.; and there are also indications that the Romans used, and to some extent repaired, the building. The attribution to Herakles rests on a passage in the orations of Cicero, who speaks of a temple near the Agora from which Verres tried to steal the bronze statue of the hero. In that temple, besides the statue, was a picture by Zeuxis representing Alkmena and the infant Herakles in his cradle strangling the serpent. There is no satisfactory proof, however, that the building mentioned by Cicero is identical with the one which I have described. About 45 metres east of the temple are the ruined remains of the altar.

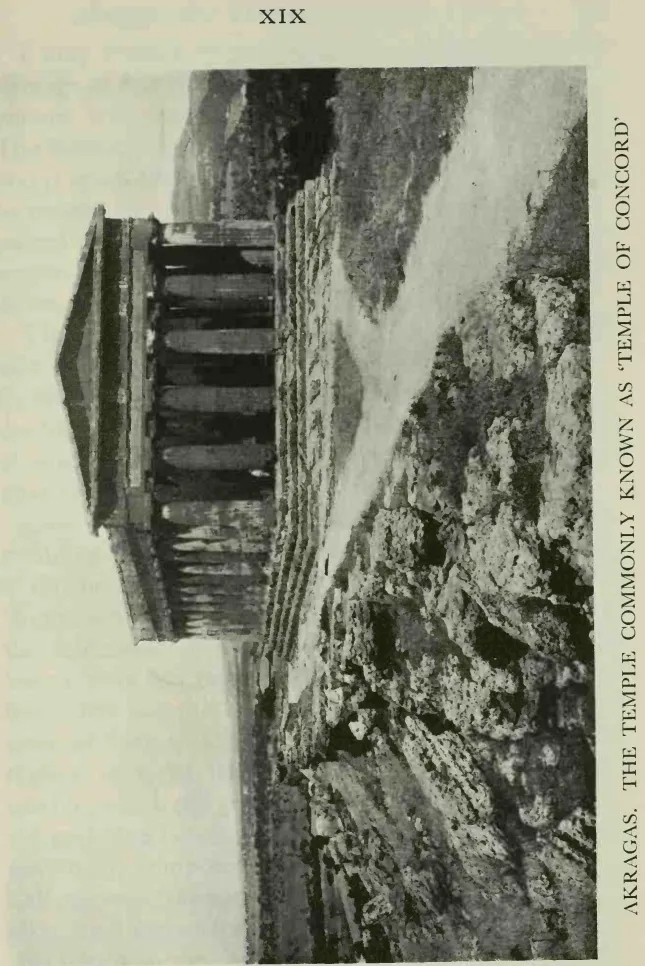

The next great building to the east of this is the finest and most complete of all. It is commonly, though quite erroneously, known as the temple of ‘Concord’. Like the Herakleion it is of peripteral form with a cella ‘in antis’. There are thirteen columns on each of the long sides and six at each end; the total length, including the steps, is just over 42 metres and the width just under 20. This splendid temple, which is one of the most perfect of all that have survived from antiquity, was erected half a century later than its neighbour. It is ascribed to the years 450–440 B.C., which is after the death of Theron. Its remarkable preservation is due to the fact that it was converted during the Middle Ages into a church; this use accounts for the arched openings in the sides of the cella.

I may remark in passing that a good deal of the damage at Agrigento which is put down to the Carthaginians was probably done by fanatical Christians. The Romans undoubtedly used several of the temples, and it is not likely that they would have allowed them to remain in a ruinous condition if they could be repaired with a little labour and expense. There is every reason to believe that all the temples were in good condition at the beginning of the Christian era.

The staircases which lead up to the roof from each side of the vestibule are a peculiar feature of the Sicilian temples. In the case of ‘Concord’ there is no doubt that there was a roof of tiles, laid on a cross-work of wooden beams, the holes for which are still visible near the tops of the walls.

East of the temple of ‘Concord’ and precisely resembling it in style, though far less perfectly preserved, is the temple called by the equally absurd name of ‘Juno Lacinia’. It stands in a commanding position at the south-east corner of the city walls. Each of its longer sides has thirteen columns and each of its two fronts has six; the measurements are very nearly the same as those of ‘Concord’. In this instance the actual roofing material has been found, viz. tiles of white marble, which still retain traces of their colouring with red and blue bands. Traces have been found also of a pavement, composed of white slabs. Fourteen and a half metres to the east of the temple is its well-preserved altar, 29.8 metres long by 7.5 wide; it is possible that it was joined to the front of the building by a low wall.

We may now return to the ‘Porta Aurea’, the principal gate in the southern wall, through which the main road passed even in ancient days. The position of the Agora just within the gate is pretty certainly fixed by Livy’s description of the capture of the city by the Romans. Taking the left turn from the gate, and passing the Roman monument so absurdly called the ‘tomb of Theron’, we come to a little temple in the fields which has a peculiar charm and romantic interest. It has no doubt been rightly identified as the temple of Asklepios mentioned by Polybius and by Cicero. The latter in his speech against Verres states that it contained a famous statue of Apollo attributed to Myron, which was carried off to Carthage by the conquerors, and afterwards restored to its home like many o...