![]()

MOVING THE OBELISKS

IN the middle of Central Park in New York stands a tall stone on a quiet, wooded knoll. It has stood here for 70 years and in this time has witnessed the neighboring streets swell in activity from suburban quiet into the busiest thorofares of all time. It has watched great buildings grow from the ground and it has been dwarfed by their eminence and bulk. It can, in all truth, say: “I have witnessed this great change in only one-fiftieth of my existence, for in my youth in Egypt I have had Moses look upon my face, and Joseph has paused within my shadow. I have seen a great city, as great as yours, burn and disappear and I have stood near the sea for 2000 years to witness another great city blossom and die. Be not proud, for I shall exist when all this brick and steel about me has crumbled into dust!”

This stone and others like it have been quarried, cut, engraved and erected by men for reasons of interest to us. They have been chiseled, raised, lowered and moved again by methods revealing to our engineers. Let him who can pause in his busy day to see what others have done, read further.

(Left): Frontispiece of Fontana’s book on the transportation of the Vatican obelisk, published in Rome in 1590. This engraving shows the engineer-architect at age 46, shortly after his triumph. He holds a model of the obelisk and wears the insignia of his knighthood.

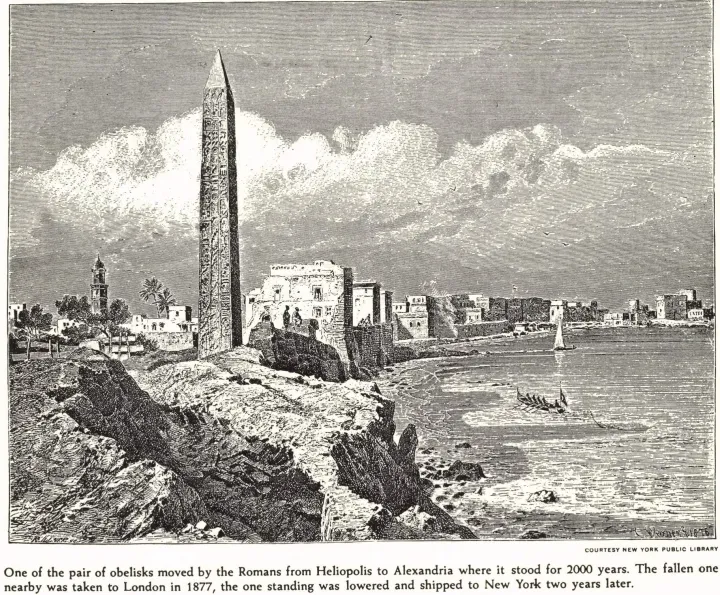

THE OBELISK was one of the three forms of monuments that evolved during the long history of the Egyptian state and religion, the other two being the sphinx and the pyramid. The form of the obelisk changed comparatively little in the two thousand years in which it was cut and mounted. Being monolithic in construction and tall and attractive in form, it still was not too massive to be moved by those who coveted its possession. The 200 to 500 ton shaft therefore became an item to be marked by the victorious invader and a challenge to his engineer to remove such a handsome trophy from Egypt and to have it set up in some distant land. That is why these superbly carved granite shafts, intended for some Nile necropolis or to adorn some temple, can be seen today, after three or four thousand years, as a trophy in Rome, or as a gift in London, Paris or New York. These ancient monuments are symbols not only of a religion no longer practiced, inscribed in a language unknown for the last thousand years, but also a challenge to the ability and ingenuity of the mason and the engineer right up to our own day. It must be noted that altho’ there are more than two score of obelisks and fragments still in existence{1} as evidence of the original craftsmanship, it still is a subject of high speculation as to how these great stones were shaped, moved and erected by men who had only the most primitive mechanical aids and no mechanical power as we know it today. Within the last century, three obelisks were moved from Egypt to the north and the west. These were one from Luxor in Egypt to Paris in 1836, one from Alexandria to London in 1877 and one from Alexandria to New York in 1880. Even tho’ steam engines, hydraulic jacks, steel cables and steel structural members were at their disposal, the mere moving and erecting of each of these obelisks became, to modern engineers, a major project of international interest and concern. Not only did the Egyptian engineers not have such modern aids but the cutting and finishing of the hard granite, its transportation over hundreds of miles, and its erecting, were accomplished by these ancients with a modesty that has kept such deeds from being adequately recorded. Whereas there exist thousands of sculptures, has-reliefs, gems, paintings, papyri and models of the religious, regal and domestic life of the Egyptians, their advanced technology is illustrated by extremely few known examples. We must therefore reconstruct their tools and methods from the results they achieved.

Excluding the moving and erecting of the three obelisks that were transported in the last century, we are fortunate to have clear records of the mechanics used in the moving and erection of the Vatican obelisk in 1586. Unlike the former, in which modern mechanical aids were used, the obelisk standing today in the Piazza of St. Peter’s, Rome, was moved by means that must have, in some measure, resembled those used by the Roman engineers, if not by the Egyptians themselves.

Egyptian Engineering

IN THE SPAN of 3500 years in which Egyptian civilization flourished, it was able to develop and support masons and engineers having highly developed mechanical skills and very high standards of perfection. There are today graven in stone or written upon linen and papyri, records of astronomical and mathematical computations, chemical, pharmaceutical and technological processes that must have involved guild practices and the maintenance of long records. Such records extend as far back as the Third Dynasty, or nearly 2800 years B.C., some time after Cheops had built the great pyramids in 3700 B.C. Later the conqueror and builder, Rameses II (19th Dynasty, 1400 B.C.), had massive statues of himself erected which, when completed, weighed about 1000 tons each. The one standing in the Memmonium at Thebes weighed 900 tons and was transported an overland distance of 138 miles. The pharaoh, Amenhotep III, similarly had carved colossal statues weighing 800 and 1000 tons that were erected 3500 years ago at Thebes. At Tanis in lower Egypt there was found the remains of a statue of Rameses so great that the large toe was the size of a man’s body. When complete it must have stood 92 feet high and weighed more than 1000 tons. The remainder of this massive statue had been carved up by Orsoken II in 900 B.C. for the construction of a temple pylon.

So prolific were the Egyptians in the cutting and placing of their monuments, that many are still to be seen there even tho’ 2000 statues, it has been written{2}, were carried off to Babylon, while dozens of obelisks have been taken to Nineveh, Constantinople and Italy, in addition to those mentioned earlier. The pharaohs who built of hard and durable granite in such great bulk and quantity did so knowing how destructive later man might be, for were it not for this vandalism, nearly all the monuments of Egypt would be standing there today. The city of Memphis was taken apart stone by stone to build Cairo, leaving only the statue of Rameses standing in the sandy waste.

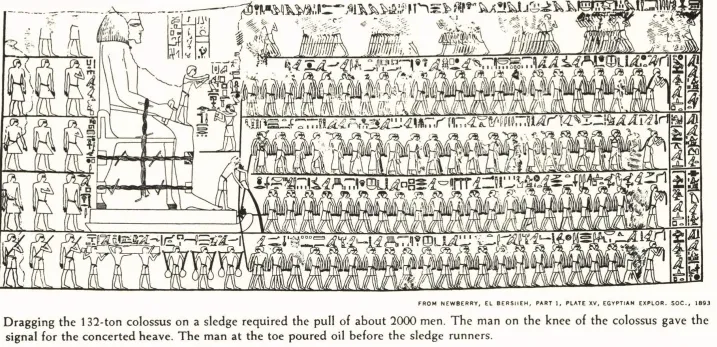

Egyptian engineers performed their great tasks depending upon such simple mechanical means as the lever, roller, inclined plane and wedge—and much muscle power. They may have used the capstan but seemingly did not know the compound pulley. What they lacked in mechanical advantages they made up in great amounts of disciplined and coordinated manpower. The emphasis seemed more on the human muscles than that of animals because the human muscles could be better coordinated and controlled. To these basic mechanical aids, Roman engineers later added the power of torsion from a twisted rope, shrinkage from wetting and the elasticity of the spring. The brace-and-bit and the whip-drill for boring holes are shown on tomb paintings, tho’ the bit was probably the spoon and not the screw type. The inclined plane or ramp was one of the most frequently used helps, for at Gizeh the remains of two inclined planes still exist. Sun-dried brick made of Nile mud (as described in Biblical accounts), was readily available for the building up of the great volumes needed to construct the causeways and ramps as required in the construction process.

Egypt, at its height, was the most populated country in all history, exceeding in density per square mile even our own records. Manpower was therefore in great abundance and from the social character of Egypt’s institutions, readily available. Her 11,500 square miles held a population of 8,000,000, or a population density of 700 per square mile, approached today only by Holland and Belgium. China’s population density is 120, and India’s, 107. Survival was relatively easy in a warm land abundant in dates and durra, a form of millet or guinea-corn. During the season that the Nile flooded, the unemployed agricultural population was put to work on various construction projects including the tombs and personal monuments of the pharaohs. The number of men working on the great pyramid of Cheops (3730 B.C.) required the labor of 100,000 men according to Herodotus (366,000 according to Diodorus){3}, working 20 years to erect this, the largest and oldest of man’s monuments. The outer and chamber stones of this pyramid were carved at Syene, 560 miles up the Nile, and some weighed up to 60 tons. The gallery and outer stone faces were polished like glass and were joined almost invisibly; the fill was of limestone blocks. The inclined stone-topped road leading to the pyramid required as much manpower to build as the pyramid itself, for this road required about four times the volume in brick and stone chips. The completed pyramid of Cheops weighed 6,740,000 tons. Commander Barber{4} has calculated that if this great monument were to be budged by the human muscle power that went into its construction it would require the simultaneous heave of over 100 million men. He is convinced that only human labor went into the construction of the pyramid. In the 1200s A.D. this monument was recorded as being in perfect condition. Since then, its granite cover was stripped to provide stones for the building of Cairo.

The indications are that oxen were used for dragging stones of comparatively small size. Horses were introduced only after the Eighteenth Dynasty, the period of the Semitic Shepherd Kings called the Hyksos, a period we have learnt about from the Biblical accounts. It was the muscle power of man rather than of draft animals that provided the greatest source of power for moving these large stones and monuments that have become so characteristic of the Egyptian social order.

The Great Wall of China was built in the short space of only ten years and represents the greatest single engineering task man has ever completed. It was finished in 204 B.C., is 1500 miles long (it would stretch from New York to beyond Houston, Texas), is 30 feet to 40 feet high, 25 feet thick, and has towers at frequent intervals. It is built of bricks weighing approximately 60 pounds, with rubble fill. It crosses mountainous territory and at one peak reaches an elevation of 5,000 feet.

In Hyderabad there was hewn the remarkable temple or Kylas at Ellora. This is a veritable cathedral cut out of solid rock 365 feet long, 192 feet wide and 96 feet high, with chambers hollowed out and walls decorated in stone sculpture, both inside and out. When one ponders at the chipping required in the shaping of even a simple stone, the man-hours that must have been dedicated to the forming of these great monuments is indeed awesome and proves an incontestable fact, that there were the man-hours to so give.

In the complex Egyptian religion, pantheistic and given to animal worship, the statue of the pharaoh was equivalent to that of the greatest gods. To insure such glory for the eternity that formed one of the elements of his religion, the pharaoh proceeded to immortalize himself and his station by the most permanent means he could think of—a granite monument to himself—making sure that all his titles were engraved upon it. It is therefore natural that the architectural form into which the symbols of glory evolved should have such stable forms as the pyramid, colossus and pylon. The obelisk form is less easily understood and there is no agreement among authorities as to why it assumed its general shape. Some believe it to be an evolution of a phallic symbol, others the representation of a ray of sunlight, thereby dedicating the obelisk to Ra, god of the sun. The Romans believed it to be a gnomon, or sundial, and tried to put it to that use. It appears that obelisks, dedicated to the rising sun, were erected on the east bank of the Nile, but pyramids, the mausolea of the kings, on the west bank.

Of the hundreds of obelisks that once glistened under the Egyptian sun, the number has been reduced to a grand total of less than 50. Although some may have fallen due to the ravages of earthquake and of time, it seems that the vast majority have disappeared because of the hunt for treasure, the religious fanaticism of competing cults and those who altered monuments to emphasize their own greater glory. Of the few that have remained, even fewer are of authentic Egyptian origin or in good condition. The greatest cluster of obelisks existed in the ancient city of Heliopolis, near modern Cairo, put there mainly under Usortesen I of the 12th Dynasty, and followed by his successors for a thousand years. It was in the shadow of the “upright stone” as mentioned in Jeremiah (xliii: 13) that Joseph was wedded to the daughter of the high priest. Near the obelisks, in addition to the university, there stood the Temple of the Sun, rivaled only by the shrine of Ptah at Memphis, the most ancient of all Egyptian temples, a temple which at one time was served by 13,000 priests and servants. Heliopolis is referred to in the Bible by the name On and in Egyptian by Annu, meaning obelisks. At its university studied Moses (Acts, vii: 22), and later its streets were trodden by Solon, lawgiver of Athens, and by Thales of Miletus who first described an electrical phenomenon. Its library was the largest in the ancient world; it was transferred to Alexandria by Ptolemy Soter in 305 B.C. At the time ...