![]()

THE ARTIST AS MUSE

![]()

JUAN DE PAREJA A Face of Freedom

![]()

In 1650, the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez exhibited an extraordinary portrait at the annual art exhibition in Rome’s Pantheon. Depicted from the waist up, before a shadowy background, a dignified Afro-Latino man proudly holds one arm across his chest. He is elegantly dressed, wearing a charcoal grey cloak, sword belt and large white collar that contrasts with his natural curly black hair, dark beard and eyes. Glowing radiantly in the light that falls upon his face, the sitter stares directly, and powerfully, at the viewer.

When Velázquez’s painting Juan de Pareja (1650) was unveiled, it caused quite a sensation, particularly among his fellow artists. According to the eighteenth-century biographer Antonio Palomino, it was ‘applauded by all the painters from different countries, who said that the other pictures in the show were art but this one alone was “truth”.’ But was this stately painting really an image of truth when the man Velázquez had portrayed – in such magnificent terms – was, in fact, enslaved by him? Was he not concealing, rather than revealing, reality?

The son of an African-descended woman named Zulema and a Spanish father called Juan, de Pareja was born into slavery in around 1610 in Antequera, near the active slave port of Málaga. It isn’t known if he was purchased or inherited by Velázquez, but some time after 1631 de Pareja joined the Spanish painter’s studio as his enslaved assistant. There, his duties would have involved helping the artist by grinding pigments, stretching canvases and creating varnishes, among other practical tasks.

Since the Renaissance, artists have enlisted the help of studio assistants not only in the preparation of materials, but in the process of creating artworks. Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt van Rijn and Michelangelo are among the ‘Old Masters’ whose renowned paintings have involved the silent hand of others, including enslaved persons, students and servants. It is therefore also highly likely that de Pareja would have collaborated with Velázquez on the creation of commissioned portraits.

De Pareja may even have helped to represent royalty, as by the time he entered into Velázquez’s studio his master was an official court artist in Spain. Known for his precise realism, Velázquez was employed to paint grand portraits of King Philip IV, his wives and children, and other members of the royal household. In formal posed portraits, Velázquez captured the folds and textures of his sitters’ sweeping regal robes and endowed his paying royal superiors with an air of dazzling majesty.

It is in this very same manner that Velázquez chose to represent de Pareja, a muse he was inspired, rather than paid, to paint. There is no indication at all that his sitter is an enslaved person; in fact, far from it – in place of coarse plain clothes, de Pareja is dressed in a close-fitting grey jacket and matching cloak slung fashionably across one shoulder to reveal a sword belt; laid across his shoulders is a bright white lace collar. This painting of striking colour contrasts recalls Velázquez’s Portrait of Philip IV in Armour, in which the King is dressed in arresting gold and black armour with a crimson sash across his chest.

Like the King, de Pareja has also been illuminated through the use of theatrical lighting, which falls across his face onto his forehead, cheeks and lips. He holds himself confidently, twisting his body slightly to his right, while staring straight at the viewer. There is a defiance about this imposing depiction of de Pareja, particularly given the ways in which slaves were typically characterised in formal and commissioned portraits at this time.

Since owning an enslaved person or servant signalled power and wealth, subservient Black figures were often included in portraits as a means of confirming their white owners’ status. For instance, in Jan Verkolje’s portrait of Dutch city councillor Johan de la Faille (1674) a young Black male, positioned to his finely dressed master’s left, bends down in order to hold the leashes of the white man’s hunting dogs. Not only does he stoop over deferentially, but exists quite literally in his master’s shadow; unnamed and symbolically relegated to the corner of the composition, his individuality has been denied.

Breaking such conventions, Velázquez elevated de Pareja from an anonymous commodity in the background to worthy subject, even naming him in the portrait’s title. At the time, it would have been considered an honour to have been painted in these terms by an artist of Velázquez’s standing, and particularly if you were an enslaved person. Given that Velázquez could have portrayed de Pareja exactly as he pleased, it’s striking that he decided to render him with such gravitas. Why, then, was the painter championing an enslaved person in this manner?

Perhaps Velázquez had recognised the direct parallel which existed between him and de Pareja. Just as his studio assistant worked for him, Velázquez existed in deference to the royal family, providing them with flattering portraits; although not to the same degree, his own dynamic echoed the relationship between enslaved person and enslaver. Just as de Pareja was beholden to Velázquez, the latter served the King, and in the same context – as both men were artists. Had the painter seen something of himself in his subject?

Velázquez does seem to suggest de Pareja’s status as an artist in the portrait: a slight tear in his sleeve indicates the arm of a man involved in stretching, priming and painting canvases – perhaps even this one. A master of verisimilitude, was Velázquez sewing truth into the detail of his canvas in order to recognise an enslaved person as an artist?

Velázquez would not have been the first artist–master to have taken a studio assistant as his muse. Leonardo da Vinci was famously inspired to create drawings and paintings of his young servant, assistant and apprentice Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno who joined him at the age of just ten. In his journals, da Vinci describes him as a troublemaker, detailing how this ‘thief’ and ‘liar’ frequently stole items and broke things, earning him the nickname Salaì, meaning ‘Little Devil’.

Although mischievous, Salaì is easily identifiable in paintings such as Saint John the Baptist (c.1513–16) through his angelic appearance, beautiful curly hair and enigmatic smile. Some researchers even believe that it was Salaì, and not Lisa del Giocondo, who was the real model for the Mona Lisa: the letters which form ‘Mona Lisa’ can be rearranged to form ‘Mon Salaì’. It’s widely thought that da Vinci entered into a sexual relationship with Salaì, who stayed with him for over twenty-five years as a servant, apprentice and muse and, learning from his master, later became a talented artist in his own right. Of course, this relationship highlights the issue of power imbalances which have existed not only between female muses and male artists, but in same-sex pairings, particularly within the era of Renaissance Florence which allowed for pederastic relations.

Despite this, there is no indication that any romance existed between Velázquez and de Pareja, though the artist and muse certainly developed a close personal relationship. It’s known that de Pareja acted as an important legal witness for the signing of several documents, including a power of attorney, dating from 1634 to 1653. De Pareja also accompanied his master on the significant trip to Rome where his portrait was first shown to the public.

Standing side by side with his portrait, the striking likeness between real-life muse and painted version would have been immediately visible to viewers, leading painters to remark on the ‘truth’ of the picture. Palomino also writes in his biography that Velázquez sent de Pareja to present his portrait to some influential Roman friends: ‘They stood staring at the painted canvas, and then at the original, with admiration and amazement, not knowing which they should address and which would answer them.’

Perhaps, then, Velázquez had purposely painted his muse in this hyper-realistic manner as a means of showing off his skill and impressing his contemporaries. He once remarked on his desire to stand out: ‘I would rather be the first painter of common things than second in higher art.’ With this unique and breathtakingly beautiful portrait of a Black enslaved person, elevated to the status of royalty, Velázquez would surely have demonstrated that he was the finest painter of everyday life. Could this, then, be a way of using de Pareja to make a statement?

Acting as an advertisement for his talents, Velázquez could certainly have used this portrait to garner interest for future commissions, particularly as his portraits of the Royal Family would not have been available for the public to view. In contrast, he owned this portrait of de Pareja, just as he owned the enslaved man himself, and would therefore have been able to do what he wanted with it. If this was the strategy behind the artwork, it surely worked: Velázquez was awarded the commission to paint Pope Innocent X – one of the most influential people in the whole of Europe – later that year.

But Velázquez could easily have chosen to depict a number of potential subjects, such as his pupil, studio assistant and son-in-law, Juan Bautista del Mazo, who succeeded him as court painter to Philip IV of Spain. Moreover, in Velázquez’s sympathetic and humanising portrayal of his muse, an affection can be felt for the man whom he came to trust. De Pareja exists beyond a performed status: although he stands proudly, there is a haunting sorrow within his dark eyes, expression and stance. As American contemporary painter Julie Mehretu points out, ‘the slipping of his hand under his shawl pulls you to that part of him, just under his heart… the piercing look, it’s not contempt, I don’t read it as rageful or angry and it’s not resignation but this very conflicted implicit sadness’.

Velázquez is also, then, telling viewers the story of a man who had no rights of his own at this time. However, that was soon about to change: just months after completing this portrait, Velázquez gave de Pareja back his freedom. Held in the state archive of Rome is the document of his manumission, showing that Velázquez signed a contract on 23 November 1650 that would accord de Pareja his freedom – after another four years of service – in 1654. It’s impossible to know if Velázquez took this decision on his own, and some legends describe how it was King Philip IV who demanded the emancipation of de Pareja after seeing his talents as an artist. Either way, by painting him with such majesty, Velázquez seems to anticipate freeing the enslaved man in real life.

Ultimately, from 1654 onwards de Pareja forged a successful career as a portraitist. Making the transition from an enslaved person to a free man and a painter, he created highly accomplished portraits of notable figures including the architect José Ratés Dalmau, the priest and playwright Agustín Moreto, and even the King of Spain, Philip IV. De Pareja also painted a number of biblical characters and scenes. One of his greatest works, which survives today, is The Calling of Saint Matthew (1661), which represents the biblical story of Jesus asking Matthew to become one of his disciples. Matthew, a tax collector, is seated at a table with a bag of gold coins before him; but, raising a hand to his chest, he turns to look at Christ who stands behind him on the right-hand side of the painting, choosing this new life.

Almost mirroring Christ, and at the far left of the composition, stands another significant figure. Wearing an olive-green doublet with matching breeches and stockings, a smart white collar and cuffs is de Pareja, who stares directly at the viewer. Not only has he portrayed himself as a gentleman and witness to this evangelical event, but in his right hand he also holds a piece of paper on which his signature is visible. By signing this document, and by extension the painting, de Pareja asserts his identity as a free and professional painter.

In turning this scene into a self-portrait, de Pareja echoes one of the most famous paintings by his former master, Las Meninas (1656). Velázquez’s canvas features the family of King Philip IV, including his daughter and several ladies-in-waiting, within the royal palace. Standing on the left, in front of a huge canvas, is Velázquez, who gazes out towards the viewer. Just as Black enslaved persons are sidelined in formal portraits, Velázquez has positioned himself, as a serving artist, on the edge of the group of subjects.

Directly mimicking Velázquez’s self-portrait, de Pareja demands that he is seen in the same light as his former master: he, too, is an artist. This painting also recalls Velázquez’s portrait of de Pareja himself – here standing in exactly the same pose, gazing out at the viewer, and, although painted a decade later, he looks to be exactly the same age. By taking himself as his own muse de Pareja not only identifies with, but also endorses, Velázquez’s earlier representation of him.

However, there is one discernible difference between de Pareja’s self-representation and his depiction by Velázquez: the freed painter seems to have lightened his skin. In Spanish society at this time, having a darker complexion was equated with slavery, and de Pareja would no doubt have faced prejudice despite his status as a free man and professional painter. As Professor of Hispanic Art History Carmen Fracchia points out, ‘this statement was the only clear way that Pareja found to convey his status as a man free from the stigma of slavery when the blackness of his skin would always have reminded his audiences of his enslavement’.

It’s telling that Velázquez felt no need to lighten the skin of de Pareja; he would not have been affected by the portrayal, whereas de Pareja was, in effect, forced to alter his appearance, given the judgement he would have faced based on his skin colour. De Pareja’s self-portrait does, then, also reflect the fact that he was never completely free: in 1660, he became the servant of Velázquez’s son-in-law, the court painter Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, employed in his workshop. De Pareja remained loyal to Velázquez’s family until the very end of his life in 1670.

Today, de Pareja and his story live on in his portrait. It’s likely that Velázquez sold the painting to one of the Italians who admired it in Rome, and it was subsequently passed between private collections until 1970 when it came up for sale. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York bought it for a then record-breaking £2,310,000, declaring it ‘among the most beautiful, most living portraits ever painted’ and one of the ‘most important acquisitions in the Museum’s history’.

The incredible likeness of de Pareja, which first astounded viewers at the Pantheon, continues to move contemporary audiences. Hung in a gallery of Velázquez paintings, de Pareja stands side by side, and on equal terms, with the artist’s elite and royal sitters; none, however, have quite the same emotional presence as de Pareja. Although he is not represented in the conventional manner of an enslaved person, there is no illusion here, only integrity: this is a studio assistant, an artist and, above all, a man worth painting. Velázquez has conveyed his muse’s dignity and true worth in spite of his societal status – which de Pareja confirmed by later portraying himself, as a free man, in this same image.

![]()

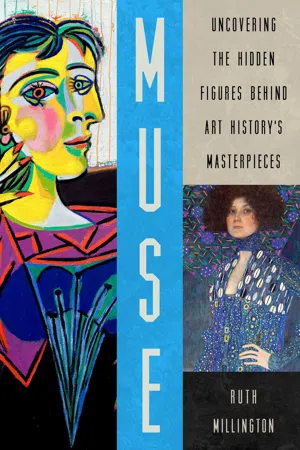

DORA MAAR The Weeping Woman

![]()

Pablo Picasso, one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, is associated most of all with pioneering cubism. In his art, he created a new way of looking at the world through abstracted, intersecting and fragmented forms. However, Picasso is just as famous for his tangled, romantic relationships; the women in his life provided inspiration for some of his most admired portraits, most notably The Weeping Woman (1937). Who was the muse for this cubist masterpiece, and why is she crying? To find out, we need to go back in time, one year earlier, to a café in Paris.

In 1936, Paris was a bohemian centre of art, film and literature. The French capital attracted avant-garde artists, writers and intellectuals from around the world, offering them the opportunity to exhibit in salons and expositions, attend influential art schools, and make a name for themselves. This freedom helped the city to birth many major modern art movements: impressionism, Fauvism, Dada, surrealism and, of course, cubism. During the 1920s and ’30s, the creatives of Paris would rendezvous at an art deco-styled café, located in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, called Les Deux Magots. This meeting place for writers, philosophers and artists welcomed the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, alongside Fernand Léger, Joan Miró and Picasso. Another artist who often came to this legendary café was the talented photographer Dora Maar.

The story of Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso’s first encounter has been much mythologised: it is said that Maar, aged twenty-nine at the time, was seated alone at Les Deux Magots, playing a game in which she stabbed a penknife between her fingers into the wood of the table. Years later, the episode was described in detail by another of Picasso’s models and lovers, Françoise Gilot, in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro:

Dora Maar wore black gloves with little roses. She took off her gloves and took a long, pointed knife that she stabbed into the table between her spr...