How choosing a narrow audience can broaden your reach

Why finding points of connection makes readers more receptive

How to choose a specific audience

Although language is still pretty recent in an evolutionary context, it has been with humans for millennia, shaping our brains and behaviors. As individuals, most of us have been learning from and sharing with other people our entire lives. Each of us carries within us enormous amounts of working knowledge about how to communicate.

Think about it for a moment. You automatically adopt different explanatory styles based on the person you are addressing. If a three-year-old asks you how your phone works, you’ll give a different answer than you would to an adult colleague. Faced with someone returning to civilization after two decades in the wilderness, you’d come up with a different approach altogether. You automatically make decisions and shift your explanations based on what you know about the other person, as well as real-time feedback such as questions or confused expressions.

Yet when we write, those absent readers become less real to us, and we lose the benefit of a lifetime of acquired skills. We become entranced with our own words or caught up in our subject and write for ourselves or for some faceless, anonymous “general public.” Everybody suffers when this happens.

To improve your nonfiction writing, first bring the reader back into the equation. When you picture a real person, you can activate that almost-instinctive knowledge you’ve acquired about communicating.

The Unknown Reader

While it may feel like a one-way street, writing does not fulfill its purpose until someone reads and understands the words.

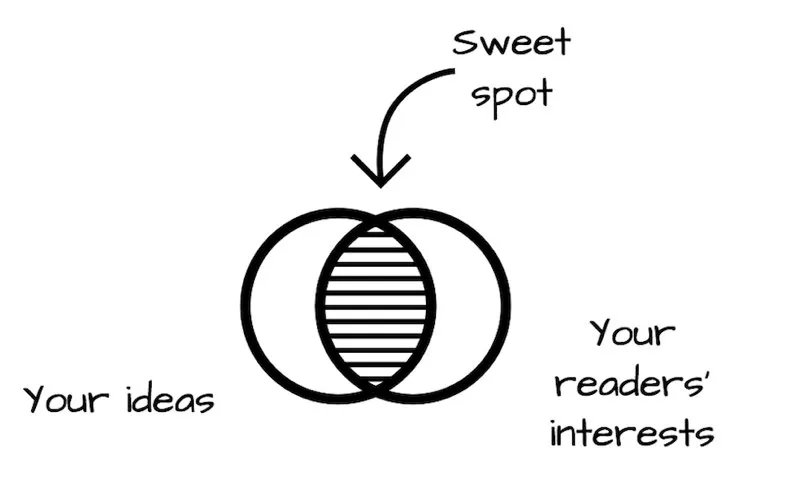

Remember the Venn diagram in the introduction: what you want to write, and what the reader needs to see?

To find the area of overlap, you must understand the reader’s needs and context. For many writers, this is the most pressing and difficult problem to solve.

So, who’s your reader?

If you’ve honed your writing skills in an academic context, this question may be easy to answer. Whether writing papers for classes or peer-reviewed journal articles, you have a fairly accurate sense of the audience, including their background knowledge and why they’re reading your work. The same holds true when you write for people in your industry; you understand their roles and needs.

This background knowledge is missing when you address a general, unknown audience. The potential world of readers is as broad and wide as the ocean. Authors who are expert in their fields can fall prey to one of two conflicting temptations in this situation:

- They stick to writing for readers they know, such as colleagues or people like them. Academic researchers who present dense, scholarly works to a general audience limit the potential scope and impact of their efforts.

- Conversely, they may attempt to write for everyone, assuming that the reader brings nothing to the conversation. This approach often results in a generic, dull description that interests no one.

No matter how compelling you find your topic, you won’t reach everyone—that’s a given. The more specific you are in visualizing the target reader, the more effectively you can write. Put aside your fascination with the subject and pick a target audience.

Pick an Audience, Any Audience

Thinking of a specific person activates your built-in communication skills, using your life-long training in human interaction to make decisions about the writing. Knowing your reader influences the words you choose, the sentences you craft, and even the approach you use to present your ideas.

Many writers make the common mistake of being too vague when picturing a reader. When it comes to identifying a target audience: everyone is no one.

You may worry about excluding other people if you write specifically for one individual. Relax—that doesn’t necessarily happen. A well-defined audience simplifies decisions about explanations and word choice. Your style may become more distinctive, in a way that attracts people beyond the target reader.

Andy Weir wrote The Martian for science fiction readers who want their stories firmly grounded in scientific fact, and perhaps rocket scientists who enjoy science fiction. I belong to neither audience, yet I enjoyed the book. Weir was so successful at pleasing his target audience that they shared it widely and enthusiastically. Because Weir didn’t try to cater to everyone, he wrote something that delighted his core audience. Eventually, his work traveled far beyond that sphere.

It may be counterintuitive, but if you want to reach a larger audience, consider concentrating more closely on a specific segment of it. To broaden your impact, tighten your focus on the reader.

Once you’ve chosen a target reader or two, make a list of the identities, beliefs, or experiences you may have in common. Particularly when you’re trying to reach people outside your field, or readers with different beliefs, these connection points offer clues as to how to proceed to earn and sustain the readers’ attention.

Forging a Shared Identity with the Reader

In the Prologue of her memoir, Lab Girl, Hope Jahren starts by asking you (the reader) to look out the window and contemplate a leaf on a tree. After discussing possible factors to explore (its shape, color, veins, and more), she prompts you to pose a specific question about your leaf. Then she makes a surprising assertion.1

Guess what? You are now a scientist. People will tell you that you have to know math to be a scientist, or physics, or chemistry… What comes first is a question, and you’re already there.

Because you asked a question, you are a scientist and one of her colleagues—and therefore have stake in her story.

We get so caught up in our subjects, we often forget about the readers. When writing about sensitive or challenging subjects, the readers may be the most important part of the story. People who feel they share something in common with you are more likely to be open to your ideas.

In 2016, a team of researchers led by the Harvard School of Education surveyed ninth-grade teachers and students in a large, suburban high school in the U.S. More than 300 students and 25 teachers answered a series of questions as part of a psychological study disguised as a “getting to know you” exercise. After receiving the questionnaires, the researchers gave students and teachers alike feedback (manipulated, of course) about their shared characteristics and preferences. Some were told they aligned on three key points, others on five.

The researchers checked back five weeks later, asking students and teachers alike about their experiences so far. Those teachers and students who were told they shared five points of connection reported better relationships, while students earned higher grades.2

Human beings come with built-in us/them filtering. Family members are our closest groups, followed by community members, work colleagues, citizens of cities or states, and so on. We also sort and categorize people by behavior and appearance: those who look like us, dress like us, behave like us, root for the same sports teams, worship in the same way, etc.

When we first meet someone, we instinctively look for ways that we are the same or different. We’re not aware of many of these us/them filters. Deep in our primitive minds, we are trying to determine if the person poses a threat.

Despite our strong need to form groups, people also shift identities and switch between roles quick...