![]()

Arrival

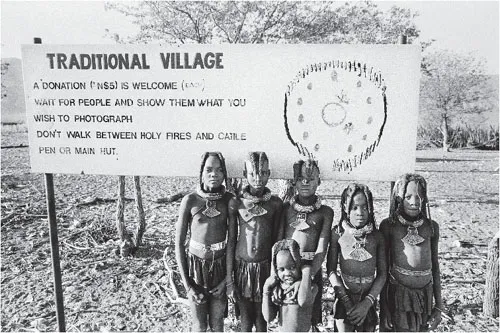

DEMONSTRATION VILLAGE

We had come to Namibia to look into the possible effects that a hydro dam would have on the Himba people. We were traveling on a grant from a human rights organization and we intended to produce articles about the situation. According to what we’d read, the Himba were opposed to the dam, saying it would kill them, while the government was determined to capitalize on the hydro power of one of the country’s few permanent rivers. We had driven from South Africa and were planning on staying as long as we could. We had been driving north for five days when the fences stopped following us. On the sixth day, the wide gravel road narrowed to a dirt track and after awhile we came to a sign telling us we had arrived at a “Traditional Village,” and warning us not to walk between “holy fires” and the cattle pen or the main hut. We parked near a circle of round mud huts and six girls came running. They pointed excitedly and seemed to want everything in sight, the blanket on the seat of our truck, the string of beads around my neck. “Candy,” said the girl who looked oldest. “Candy?” I said. “Candy,” she replied.

The girls led us over to the huts, bouncing up and down, and speaking in a language that we didn’t understand. We responded in English and the whole exchange had a giddy feel. The oldest girl walked beside me, repeating my words in her clear bright voice. The only other people in the village seemed to be an old woman and a teenage girl. The old woman sat alone, hunched over a cooking fire. We tried the greeting we had learned from a travel magazine, saying moro moro and getting moro moro in return.

We were worried about the holy fire. The sign had been explicit about not crossing the line between it and the main hut. We didn’t know where the holy fire was or how to ask about it. We kept looking and stuck close to the girls, hoping that by following them we would avoid giving offense.

The entrance to one of the huts was blocked with branches. The older girl wiggled through and emerged with a big bag of sugar. She handed out lumps to everyone, including me and David. The children chewed through theirs in a matter of minutes while I managed a polite nibble and, when no one was looking, put the lump in my pocket.

Before we left, the older girl brought over a notebook in which visitors had written their names, where they were from, and how much money they left. The village had already had several visitors that day – travelers from Germany, Switzerland, and England had donated a total of $165. When David raised his camera to take a picture, the girls lined up in formation beneath the billboard and put on serious faces. As we were driving away we had to pull aside so two Land Rovers coming towards us could pass on to the village.

CAMPGROUND

We reached Epupa Falls in the middle of the afternoon. The place reminded me of campgrounds back in Alberta where everyone parks side-by-side next to their own picnic table. All the campers seemed to have brought folding tables, chairs, and portable barbecues. Four men in short skirts with their chests bare stood nearby watching us. Under the nearest palm tree, several white men in lawn chairs were drinking beer and were also watching us.

The dog was whining to get out of the truck. When the door opened, he ran to the river and leapt in. The current bore him towards the falls and David had to scramble along the bank in order to grab his collar before the water went over the edge.

A young woman was making her way from campsite to campsite; the men drinking beer waved her away, and she came over to us. Her skin was stained red-brown and glistened in the sun; her skirt was made of goat skin and she wore thick bands of jewelry. She had a baby strapped to her back, and carried a carton of orange juice under her arm. When she stuck a finger in her mouth, I could see that her top two teeth were filed into points. She sucked on her finger and it took us awhile to figure out she was asking for a cigarette. I shook my head. The baby on her back reached out a hand; I took it and smiled, hoping the woman would stick around. I was keen to meet people, but wanted our conversation, even the limited kind we could have without a common language, to be about more than just what I could give them.

Another woman with several kids came along and crowded around, asking for candy. When David raised his camera, everyone lined up in snapshot formation. He looked frustrated and put the camera down. They asked for candy again, but it seemed wrong to give it to them when I knew they didn’t have toothbrushes; I hadn’t thought about that when I bought it. I left the candy in the truck and everyone looked disappointed and maybe a bit pissed off. The smile on my face grew stiff and the group moved on.

JACKSON

I don’t remember how Jackson approached us, but we were happy to meet an African who spoke English. We explained that we were journalists from Canada, here to make a story about the Himba. Jackson had worked with journalists before and mentioned a woman from New York who did TV shows. He explained that because he was from the Herrero tribe, he knew a lot about the Himba. He said that both groups speak the Herrero language, that they had once all been the same people. I remembered this from the reading I had done. The Himba were the part of the Herrero tribe that stayed in the northern reaches of Namibia when the rest moved south. While the Himba continued to live in the isolation of the north, the Herrero came into contact with the German colonists who were creating the country of South West Africa. War between the two broke out in 1904 and even after the Herrero surrendered, the Germans continued to pursue a policy of extermination that resulted in the death of about eighty percent of the tribe. The Herrero women are unmistakable; many still wear the wide bonnets and pioneer-style dresses of a century ago.

The next time the woman with the baby came past, David got Jackson to ask for permission to photograph her. She told Jackson it would cost the white man four dollars to take her picture. David and I felt uncomfortable with this; journalists weren’t supposed to pay for photographs, and at four dollars each we wouldn’t be able to afford a lot of pictures. David got Jackson to explain that he wanted to take many photographs and he didn’t want the woman to stare into the camera, he wanted her to ignore him and go about her life like she usually did. He offered her ten dollars and a bag of sugar on the understanding that he could take her photograph whenever he saw her. She agreed.

We decided to hire Jackson to help us for a few days. He agreed and went off to collect his things and returned an hour later wearing the same cut-off jeans and T-shirt; he had put on a safari hat, carried a small notebook, and had brought nothing else. A helicopter flew over, following the course of the river, and Jackson told us it belonged to geologists who had been doing tests related to the dam. Some of the Himba men had been working for the geologists, he said.

We walked around the area and came upon a group of men in a large canvas tent. One of them, a tall man in shorts and a Nike windbreaker, told us they were Namibian border guards. They weren’t wearing uniforms and appeared to have no weapons. The Kunene River divides Namibia from Angloa, its northern neighbor, and the pale purple hills visible on the far shore were in that war-torn country. The man in the Nike jacket began asking questions about where we were from and why we were here. We told him we were journalists from Canada doing a travel story about Namibia. He nodded knowingly, told us he was an Ovambo, the tribe of Nambia’s president, and said he was a doctor who had been trained in Cuba and Russia during the war. He complained about the lack of medical supplies at the border and asked us if we had any malaria pills.

As we spoke, a small plane circled low overhead, and then landed on the dry ground beyond the palm trees. A Toyota Land Cruiser with an open top drove up to meet it. It turned out that Epupa Falls had two luxury lodges which catered to fly in tourists. One of the lodges was surrounded by marigolds; the other was hidden behind a tall wooden fence that looked like a fortress.

Back at the campground, a group of South Africans were running a generator. I wondered if it was to keep the beer cold. We made a fire, cooked supper, and were eating with Jackson when a small man in pressed trousers arrived. His name was Amos and he explained that it would cost fifteen dollars each to camp for the night. We had just been discussing our budget with Jackson and had figured we could pay him fifty dollars a day for acting as our translator. We had been planning to stay at Epupa Falls for several weeks, and hadn’t expected to pay anything for it. We tried to barter our way into a special rate, but Amos said he didn’t have the authority to give us a deal. After he left, Jackson told us Amos was a Himba who no longer dressed like a Himba. Jackson also told us not to worry, we would go to a place where no one collects money for camping. When we finished supper, he started to do the dishes, but I felt funny about that and insisted on doing them myself. We lent him a blanket and pillow and he slept beside the fire.

TOURIST

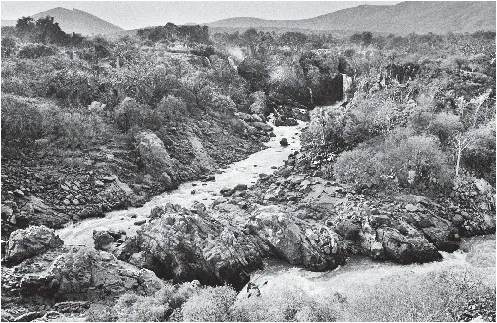

Early the next morning we walked downstream for a view of the wide stretch of cliff and water that is Epupa Falls. The border guard in the Nike windbreaker waylaid us for a few minutes before we started down the trail, asking again if we had any medicine for malaria. He admired my hiking boots and said we should send him a pair when we got back to Canada.

We scrambled down a path to a place along the shore where we could look back at more than a dozen waterfalls dropping from the cliffs. Several baobab trees clung to rocky outcrops between the falls, and David pointed at lovebirds in the bush beside us. We were both upset that the likely fate of all this was to be buried under several hundred feet of water.

We felt that we had been deceived by the newspaper article that had made us decide to come here. It had led us to believe that if the dam were stopped, the Himba would continue with their traditional ways, but already we sensed that this could never be the case. We hadn’t expected so many tourists, and from the way that Jackson seemed to be making his living as a freelance guide, we surmised that plenty of journalists moved through here too. Our own experiences were giving us a feel for the impact travelers were making.

As we sat looking at the falls, we were joined by a German engineer named Klaus, here on vacation with a tour group. When we said we thought it was wrong that this natural beauty should be flooded, Klaus talked about how valuable electricity was to a developing country. One must be realistic about these things, he said. We talked about the impact the dam would have on the people and Klaus agreed it was unfortunate, but claimed that the Himba would have to develop someday and it may as well be now. He said he believed that people are basically lazy and can’t resist the appeal of western technology. He said the Himba were always hitchhiking rides, that just like us they would rather drive. Klaus agreed that it seemed crazy to flood this place, but said that was the way the world worked. I looked at the rocks, birds, and trees, and wondered if the world might work differently. Klaus said again that you can’t change things, you must be realistic.

FIRE

We left the campground that afternoon and followed a boulder-strewn track up river to a single hut. Jackson introduced us to the young couple staying there, a brawny man and his beautiful wife, then we all sat down and Jackson explained to them what we wanted and found out what they wanted in return. Just when we had reached an agreement, another man arrived with several women and children. Jackson introduced the new man and explained that he was “a big man,” in other words a headman, who wanted us to drive him to Epupa Falls. Jackson thought it would be a good idea, so David agreed. The headman and Jackson got in the front, the wives and children in the back. Within minutes, the only person I knew in Namibia and almost everything I owned had disappeared down the road.

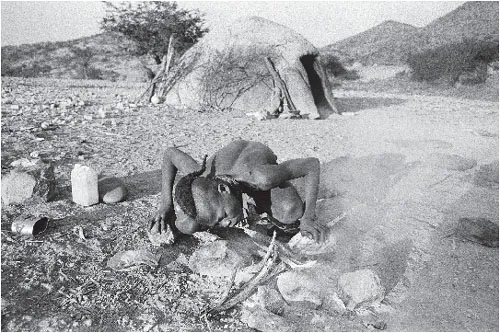

I was alone except for the goats grazing the nearby hillside and the boys who were keeping watch on them. By six o’clock the sun was going down and the temperature was dropping rapidly. Small bats were beginning to swoop through the air. I had dressed for the hot, thirty-degree day, not the near-freezing night. I warmed up by gathering rocks, setting them in a circle, and collecting wood, but I had no matches. Eager to do the right thing and cement new relationships, David and I had parted without thinking. Now, I felt both foolish and afraid.

Up a shallow ravine, through the herd of goats, smoke swirled over a fire around which the three boys sat, wrapped in blankets. It was my turn to ask a favor. I stalled, feeling embarrassed. It got colder, the light fell, and one of the bats swooped low over my camp stool. I wondered how I could carry fire, so I picked up the hibachi grill and headed toward the boys.

The boys watched me approach and when I was near gestured for me to join them. A blackened tin can was boiling on the fire while they sat turning the pages of what I recognized to be a house and garden magazine from South Africa, open at a photo of the white-walled interior of a Cape Town condo.

Rather than joining the boys, I pointed to their flame and then over to my cold pile of wood. The oldest boy pulled a smoldering branch from the fire and handed it to me. So that was how you did it. The grill hung heavy from my hand as I walked back across the rocky ground with an ember on the end of the stick. When David and Jackson drove into camp a while later, I was sitting beside a roaring fire.

MARIA

She arrived after supper, pulled up a stone and sat down, settling her young daughter between her knees. “The men have no respect for the old ways,” she said through Jackson. “My husband should have stayed to greet you but he has gone drinking at Epupa Falls so I have come instead.” She wouldn’t give us her Himba name. “I took a new name,” she said, “a better name,” and insisted we call her Maria.

We had met Maria earlier that afternoon, when Jackson had helped us negotiate with her husband. She had sat silently beside him, staring at us and pulling hard on a pipe. Her husband had rejected our initial offer, saying that the sacks of ground corn we had w...