eBook - ePub

Tweet If You Heart Jesus

Practicing Church in the Digital Reformation

Elizabeth Drescher

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tweet If You Heart Jesus

Practicing Church in the Digital Reformation

Elizabeth Drescher

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Social media has ushered in a dramatic global shift in the nature of faith, social consciousness, and relationships. How do churches navigate the Digital Reformation?

Tweet If You Heart Jesus brings the wisdom of ancient and medieval Christianity into conversation with contemporary theories of cultural change and the realities of social media, all to help churches navigate a landscape where faith, leadership, and community have taken on new meanings.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Tweet If You Heart Jesus an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Tweet If You Heart Jesus by Elizabeth Drescher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

ReligionPart I

UNDERSTANDING HABITUS

1

KICKING THE HABIT

The Complicated Technology of Cultural Change

We might possess every technological resource . . . but if our language is inadequate, our vision remains formless, our thinking and feeling are still running in the old cycles, our process may be “revolutionary” but not transformative.

—Adrienne Rich

A YouTube video called “Medieval Helpdesk (with English subtitles)”1 has entertained more than 2.6 million viewers since it made the leap from the Norwegian sitcom “Øystein og jeg” (Oys-tein and I) to the digital domain in 2007. In it, a sullen medieval monk, Brother Ansgar, sits alone in a candlelit hovel, a dark block on the desk before him. Shortly, there is a knock on the door, whereupon a smartly dressed young man enters and begins to help the monk to engage the mystery block. We see immediately that the object that vexes Brother Ansgar is a book, the “new system” that has the helpdesk technician running all over the monastery troubleshooting. Brother Ansgar, who is skilled with the traditional scroll, struggles with opening the book, turning pages, and finding his place again after the book has been closed. Although the book comes with a compact users’ manual, this, too, is in book format, and poor Brother Ansgar cannot use it, either.

The video, which has been translated into a much less entertaining English version, copied in various YouTube reenactments, and, more recently, adapted into a one-act play, is funny precisely because it so faithfully captures our frustrations with new technologies and the condescending technical support that often comes with them. The video brilliantly illustrates the personal, social, intellectual, and emotional effects of what might appear to be a very small technical or material change. The wise and knowing monk is reduced to receiving infantilizing instruction from a young techno-scribe. More than Knut Nærum, the writer of the original skit, might have been aware, this reversal of roles—the young teaching the old—would have represented a profound cultural change in the Middle Ages, new technology notwithstanding.

This particular shift did not of course occur in the Middle Ages, but it is happening regularly now, in the early days of the Digital Reformation. How many of us rely on teenagers or young adults for both technical skill coaching and general insight on the workings of computers, smartphones, the internet, and social media sites? While the dominance of youth has been growing in the U.S. popular culture at least since the end of World War II, it is only since the recent ascendency of digital technology that youthful inventors and day-to-day technology educators have come to be seen more as ordinary kids than as prodigies.

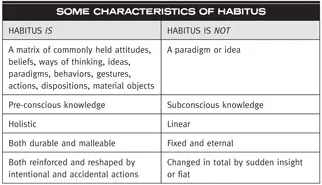

As in the case of hapless Brother Ansgar, a focus on the expertise of young people is but one indicator of a shift that is not only technological, but also cultural. Certainly the cultural changes we will explore in this book are related to technological changes, but their impact reaches far beyond the words and images on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media pages that weave new narratives of personal, social, and, for many of us, spiritual identity. Our ability to turn the page, as it were, on a new era of religious practice in which mainline churches have continuing relevance will depend on our ability to understand the changes associated with new digital media in specifically social and cultural terms. In this first chapter, then, we look in more detail at a socio-cultural framework for understanding technological change—the concept of habitus as a matrix of commonly held attitudes, ideas, ways of thinking, actions, gestures, and dispositions as well as material markers of “the way things are” in a particular time and place. Understanding the ways in which new digital social media are shaping what is clearly a radical shift in the dominant habitus of North American culture, and across Western culture more generally, opens the possibility for mainline churches to participate in this change in ways that nurture positive transformation.

Opening the Manual: The Structure of Habitus

Pierre Bourdieu, probably the most influential contemporary thinker on the concept, described habitus as “the principle generating and unifying all practices.”2 Our everyday actions in relation to one another have the effect of reinforcing what we all generally assume to be true, adapting it, or challenging it through both intentional and accidental actions. Everyone participates, like it or not. One way to think of a habitus is as something like an internalized manual of “standard operating procedures” combined with an externalized collection of “tools of the trade” for ordinary life.

Still, we don’t usually have access to a manual or some other guide that provides a wider perspective on the habitus in which we are immersed. We can never be quite sure exactly how the habitus is structured or whether, how, or when our ideas, activities, and interactions will, on their own or in aggregation with those of others, have an impact on the generally accepted understanding of “normal life.” This can make change seem somewhat random or chaotic, and that, in turn, can amplify our anxiety about what change might bring while dampening our enthusiasm for the possibilities it opens.

We do, however, have artifacts from the past that function as something like manuals for the habitus in operation in other times and places. Among the most accessible habitus guides are the monastic “rules of life” developed in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages by, for example, St. Augustine, St. Pachomious, St. Bridget, and, most famously, St. Benedict. These rules for common life stand out as articulations of an idealized, if not always realized, habitus precisely because they were set out in distinction from the more common culturally accepted practices of their day, which novices renounced as they entered into life in community. And, of course, most of us today are separated from monastic rules both by our non-monastic vocations and further still by the passage of time, so the practices described in monastic rules are all the more distinct to us.

The Benedictine Rule remains the most influential monastic rule.3 Written in the early Middle Ages, it is exquisitely detailed in its attention to the spiritual and liturgical aspects of monastic life that might seem to be the point of joining a religious order. Far beyond this, however, the Rule handles with great care the practices of communication, community, and leadership that develop out of day-to-day interactions over meals, in the course of shared work, and in the making of decisions and resolution of disputes. Benedict goes so far as to advise his charges on sleep cycles and bathroom breaks that will allow for greater attentiveness in prayer by ensuring proper digestion. This extensive spiritual and material thoughtfulness is required because the life that Benedictine monks take up insists on a studied vigilance against the ordinary, non-monastic habitus left behind. Only a detailed understanding of and rigid obedience to the Rule, from which even an abbot or abbess is not exempt, will allow monks and nuns in training to kick the habitus of secular life.

Benedictine monk or not, poor Brother Ansgar would surely have had extensive training in his youth and later professional practice involving the use of the scroll as an authoritative container of knowledge. These years of practice would have contributed not only to how he tended to think about things, but also how he physically interacted with such a container for information—his “muscle memory,” as athletes would say today. And his engagement with the scroll would have participated in the structuring of his relationships with other readers and non-readers.

If we studied monastic rules as they were written and rewritten over the centuries, up to the present day, we would learn much about how the habitus of religious communities has changed over time. Even in revisions striving to be faithful to the original visions of the founders of monastic orders, we would see adaptations, for example, to the development of Protestantism, to changes in the status of women, and, most recently, to more active participation of laypeople in monastic communities. In the process, we would certainly learn much about changes in the larger culture, too, but through a necessarily narrow, intentionally counter-culture lens.

Reformation Ready-to-Wear: How Habitus is Signaled

The thing about an ordinary, non-monastic habitus—the beauty of it, really—is that we rarely afford it as much thought as did Benedict and his followers. The commonly held assumptions, attitudes, dispositions, behaviors, and material objects that make it clear to an outsider that we belong to this place and time seem to make sense to us on their own. Clothing, for instance, plays a big part in the structuring of a habitus. This is precisely how the garb worn by vowed religious came to be called “habits” in the first place. But those of us with less restrictive dress codes are no less constrained by cultural norms with regard to what we wear. We may have more options than did Sally Field’s Flying Nun character, Sister Bertrille, but they are nonetheless organized around clearly defined categories for relatively specific purposes. Among many other things, clothes mark our gender, our age, our class, our tolerance for difference, something of our usual geographical locale, our nationality, and, as we recall from Jesus’ parable of the wedding banquet (Matthew 22), our regard for the occasion to which we have been called.

Still, however much we might fuss over exactly the right thing to wear to work, school, church, or to this or that event, we don’t usually have to think each day about the range of attire that would be considered appropriate in those settings. Nor, for that matter, do we consider whether or not clothing is needed at all. We don’t, that is, get up in the morning wondering if or how we should cover our nakedness so we can get on with the day lest we be cast out into the darkness with weeping and gnashing of teeth. (Okay, maybe Lady Gaga does, but let’s call her The Exception That Proves the Rule.)

Like clothing, other material resources demonstrate our participation in the prevailing habitus of a time and place. The kinds of homes we live in, the types of furniture that we buy, the foods we eat, the music listened to by various subsets of our cultural community, and so on all let others know that we’re from here rather than there, that we live in the present rather than the past or the future.

Cup Holders for the Reformation:

The Slow Ride to Changes in Habitus

The Slow Ride to Changes in Habitus

That said, it is important to note that a habitus isn’t subconscious, and it’s not just a set of intellectual ideas and assumptions—a paradigm (though a habitus does include the currently reigning paradigms). “How things are in these parts” is not some deep, dark secret folded into the origami of the neocortex. Rather, a habitus is the whole structure of resources and practices—ideas and assumptions, certainly, but also activities, symbols, class boundaries, stories, rituals, and so on—that are available to us as we navigate our way through life. As with a routine route to work, we could describe it in great detail if asked, but after a zillion or so back and forths, we don’t need to be all that attentive to our attentiveness. It seems like we’re “on autopilot,” but we’re really not. We simply have no need to be particularly reflective about the matrix of practices that make up ordinary, day-to-day living. Psychologists refer to this kind of “on tap” knowledge as “preconscious” or “pre-reflective” knowledge. It is the basic stuff of a habitus.

Another thing about a habitus that makes it different from, say, a passing social trend is that it is simultaneously durable and malleable. That is, a habitus extends over time, shaping our life experiences even as we, individually and collectively, subtly reshape the dominant cultural habitus through our imperfect, innovative, and sometimes impertinent practice of it.

Do you remember when, for instance, on your pre-reflective drive to and from work, cup holders became standard equipment in automobiles? If you were driving in the 1950s and ’60s, they weren’t there at all, other, perhaps, than as a slight indentation on the inside of the door of your glove compartment. You might flip the glove box open when you stopped to eat at a drive-in restaurant, but you’d certainly never drive around with a full cup of piping hot coffee. Anyone with the slightest common sense knew that was dangerous!

Nevertheless, the idea of sipping from a cup of joe on the way to work started sounding not so bad, and a series of more or less clunky options for drinking while driving developed over the next decade or so to quench this particular thirst. If, like me, you learned to drive in the late 1970s, you perhaps had one of those oh-so-attractive plastic lasso cup holders that you hooked on the inside of the front door. And, if your dad was anything like mine, you were routinely lectured about how dangerous that innocent device was any time you forgot to take it out of the family station wagon along with your 8-track tapes.

It would take until the late 1980s for cup holders to become standard equipment on cars for both drivers and passengers. The change was propelled not by new engineering insights, but by how people were actually using cars. Their innovative practice—what they did with the available resources—changed not only the automobile itself and the experience of driving, but also the process of designing cars and a life practice as basic as eating. Consuming entire meals in the car has by now become routine, helped along by greater accommodation to solitary, mobile dining built into the late modern car used in the context of longer drives from suburban homes to urban jobs. These commonplace practices of dining while driving speak volumes about our relationship to food, to our work, and to one another and mark a dramatic shift in the general American habitus over the course of the last half-century.

The cup holder didn’t cause this shift on its own, but it certainly participated in it in a big way. So goes the complicated technology of cultural change at a slow, almost imperceptible pace over time, with remarkably little fanfare despite an extensive impact on diverse aspects of our lives. The “nothing much” that is the innovation of the built-in cup holder points, on the one hand, to a complex network of changes that have occurred throughout our everyday lives. On the other, a Prius is still recognizable as a car even to someone who came of age behind the wheel of a ’63 Ford Falcon. That is, the complicated practice of automobile transportation, along with the practice of eating, has proved both durable and malleable. Thus, even as a habitus is changed by the intentional and accidental practices of ordinary people in the course of their everyday lives, other aspects of it are reinforced in the course of those same practices.

How Many Mainline Protestants Does It Take to Screw in a Reformation?: Defining Habitus in Your Community

There’s a constantly evolving series of light bulb jokes that circulates among churchy types that never seems to fail to garner a chuckle when the denominationally appropriate one is tossed into a sermon. How many Presbyterians does it take to screw in a light bulb? None. God has predestined when the lights will be on. Episcopalians? Don’t touch that light bulb! My great-grandmother donated that light bulb! Corny though these old jokes might be, they are nonetheless valuable markers of the habitus of a particular community. Before we consider the evolution of cultural habitus in the next chapter, it might be worthwhile to note the markers of habitus in your community.

What are the key stories that shape how you understand yourself as a community? What are the stories you share with visitors or newcomers to give them a sense of “how things are” in your community? How have these stories changed over time? What artifacts represent what you might think of as the essential character of your community? What practices in your common life have gone out of style or come into favor over time? Are there small changes that have turned out to make a big difference in how you function as a community? What does the way change is handled or conflicts are addressed say about who you are as a community of faith? What seems most durable? What is more malleable?

Exploring such questions as they are illustrated in our larger history is a key first step in understanding the simultaneously emerging, blended, and conflicting habitus of a faith community and the practices of communication and leadership that can support and sustain that community as it grows into the future. In the next chapter we begin facing this future by looking more closely into our shared past.

1. Available online at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQHX-SjgQvQ.

2. Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, 124.

3. See Timothy Fry, ed., The Rule of St. Benedict (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1981).

2

HABITUS BY THE BOOK

From Medieval Obedience to Digital Improvisation

The future enters into us, in order to transform itself in us, long before it happens.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

A habitus, as we’ve seen, is a remarkably intricate thing. It is matrixed across different dimensions of ordinary life. It lasts in recognizable ways over time, but is also reshaped through everyday practice, including both intentional and accidental actions. As it is lived out in any particular moment, there cannot be any one authoritative description of it, and our own understanding of how the habitus of our culture works is largely preconscious. All of this makes it difficult to hone in on a description of a habitus that is neither overwhelmingly complex nor narrowly reductionistic.

In the previous chapter, I noted that monastic rules provide some of the best documented descriptions of habitus available to us. However, as I also noted, monastic rules reflect the engagement of monks and nuns with the world outside their communities, but they are specifically designed in contrast to practices of faith and life of the ordinary believers of interest to us he...