![]()

PROCLAIM:

THE GOSPEL

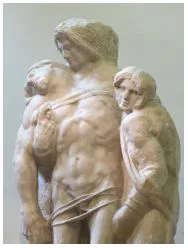

“Palestrina Pietà” attributed to Michelangelo Buonarroti (c.1555), now located in the Academy of Fine Arts, Florence, Italy. Photo ©2014 John F. Pearson. Used with permission.

![]()

1

Choose Vulnerability

Caitlin Celella

As an ice hockey player, vulnerability has never been something I prize. Being weak, giving my opponents the opportunity to hurt me, or worse, to let them score on our goalie, is the sure pathway to losing games and never seeing the playoffs. I grew up a fierce tomboy, and being vulnerable meant never getting chosen for a kickball team or failing to outrun the boys, neither of which ever seemed like good options to me. I prided myself on having a tough outer shell and a softer center that only a few could reach.

Surprisingly, the past year and a half has brought many experiences that have shown me the value of becoming vulnerable. God has been showing me, and I have been slow to notice, that I can be strong, but still know when to let others in.

Two summers ago, Bishop Jim Curry invited me to help plan an Episcopal conference on gun violence. I booked my train tickets immediately. Arriving in Baltimore in April last year [2013], with very scant information on what we were there to do, I took a taxi across the city to the cathedral where I ate dinner with the rest of the planning team—a group of twenty bishops, priests, deacons, and some laypeople. We had representations from both coasts and everywhere in between, including the Dioceses of South Dakota, Oklahoma, Colorado, Wyoming, and West Texas.

The meeting opened with norms such as respecting peoples’ privacy and ideas, and the ability to call for silent prayer at whim. Bishop Eugene Sutton of Maryland led most of that first night’s meeting. He is a tall, formidable man with a low, booming voice, standing at least three feet taller than the wooden podium he was gripping with his large hands. He spoke of listening as wearing another’s skin for a time in order to truly try on that person’s ideas and opinions. Just as I pondered that definition of listening, it was revealed that this conference was going to tackle the wider problem of violence, not just gun violence. Those from the East and West Coasts were visibly unhappy, as those from the middle of the country seemed like they wanted to escape to their hotel rooms. I was stunned and saddened that simply being Episcopalian was not enough to unite us.

However, Bishop Eugene seemed prepared for this as he refocused us. “Next on the agenda we are going to introduce ourselves. I want each of you to stand up, say your name and your diocese, and what brings you here to the planning session.”

For the next hour, everyone in the room sat rapt, listening as individuals stood up to give not only their name, but also their story. One bishop told of his brother’s suicide by a firearm many years ago. Some spoke of domestic violence or losing a parishioner to a drive-by shooting. A deacon from Wyoming talked about his state having the highest suicide rate. My introduction went like this: “My name is Caitlin Celella, I’m a lay member of St. Peter’s Church in Cheshire, Connecticut, and I’m an English as a Second Language teacher in an inner city. Recently I discovered a student of mine, a kindergartener, sitting outside the principal’s office for bringing a toy handgun to school. When I asked him why he brought it, he simply said, ‘Because I love it and I don’t want to leave it at home all alone.’ I am also here because my good friend, fellow camper and camp counselor, Becca Payne, was shot and killed in her Boston apartment a couple years ago. That night, Becca’s mother dreamt of her only child, giggling and running down the hallway of their home, only to wake up to the horrible phone call from the Boston Police Department. Someone had busted into her apartment, mistook her for someone else, and ended her life much too early.”

As everyone shared their stories, tissues were distributed, and the room seemed to grow smaller. We now knew why we were there to plan this event—every single one of us has a story of violence that we carry with us and that has changed us. On day 2 of planning, a vital question was posed: How can we get Episcopalians to engage in a conversation about violence? We knew the answer—telling our stories. We had experienced this as a sure way to become vulnerable, to allow everyone listening to wear our skin for a short time, for us to become so human and immediately relatable and accessible to those around us.

That night in Baltimore, I learned the value of telling stories as a way to connect with others, to open honest dialogue, and to pave a path for others to share. To tell your story is to share a piece of yourself, who you are, what has formed you as a person, what makes you tick, and what makes you joyful.

The second of my recent formative experiences occurred at the event we planned, which we titled “Reclaiming the Gospel of Peace: An Episcopal Gathering to Challenge the Epidemic of Violence.” My friends all wanted to know, “Why are you flying to Oklahoma City?” The planning team had chosen Oklahoma City very carefully. Our goal was to get everyone to the table—liberals, conservatives, Southerners, Northerners, the old, the young, gun owners and those who don’t own guns, and everyone in between—to have an honest conversation about the violence we see daily and what we should be doing about it. Oklahoma City was chosen with the hope of attracting people from all ends of the country to have a conversation the rest of the nation needs to have so desperately, yet cannot seem to have.

The event was held for three days just before Easter 2014 and gathered 220 Episcopalians, including thirty-four bishops, Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts-Schori, and the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby. Indeed, there were people from all ends of the country. We had accomplished our first goal of attracting lots of diverse people holding diverse views. Morning worship, Compline, and many shared meals added to our sense of unity and provided time to share our stories and ideas. Most importantly, people came prepared to have an honest discussion about violence! We asked, “What is the cause of the immense and varied violence we see? What violence am I responsible for? What should I be doing?” I was happily surprised that we were able to approach these questions honestly and with the understanding that we are all God’s children. I am a twenty-six-year-old woman from the middle of Connecticut, you are a seventy-two-year-old man from West Texas, and upon our meeting we have a familial love that comes from both being children of God. As I greet you, I know there’s an aspect of God that I can only see in you. Let’s share our stories, our concerns, and what solutions have been effective in our states.

Just as the planning team had discovered in Baltimore, telling our personal stories of violence brought us to see each other as individuals and as equals. Inviting conference participants to share their stories allowed us to begin down the long road of listening to those we had been simply labeling and pigeon-holing, placing in large groups to ignore or yell at from our own corner. Stories shared over drinks or meals or during breaks in the schedule allowed us to connect on a deeper level. The older priest sitting on my left was no longer just a guy from Southern California, as his nametag read; he was now someone who had experienced the abrupt loss of a teenager in his youth group who had committed suicide. During the conference, telling our personal stories of loss, triumph, and even effective actions from our states allowed us to leave labels behind and focus on the important issues at hand.

On the last day of the conference, we took a field trip to the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum. We trod somberly through the descriptions of that fateful day almost twenty years ago. From video footage taken by a helicopter mere minutes after the bomb detonated, to rubble dotted with small children’s sneakers and office telephones, the museum ended with a stirring “Hall of Honor” with photographs and identifying keepsakes of all 168 victims. This is a memorial of what extreme violence humans are capable of rendering.

We heard a presentation by a survivor of the Oklahoma City bombing, Melissa McLawhorn Houston, who had been working as a lawyer next to the fated Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. She spoke of crawling out from under a tepee of rubble, finally finding a stairway that would take her to the first floor, and being on autopilot as she found her car to drive home. She spoke of her grandfather, a World War II veteran, who recognized that she was “shell-shocked.” She spoke of survivor guilt and her feeling that she should not be alive, her questions about why she was left to live. She went on to work with a group in Washington, DC, to craft some of the nation’s first antiterrorism legislation. Melissa said, “One of the biggest ingredients that we see in terrorists is a lack of hope. If you don’t have your own sense of hopefulness for your own life, that’s where a lot of that starts from.”

I thought about how painful it must be for this brave woman to share her story of violence over and over again. She was volunteering to become vulnerable in order to give people a firsthand account of the bombing and how it changed her life. She spoke of a sense of hope for one’s own life, which can be fostered by inviting someone in, including them in a group or community, showing them they are worthwhile and loved. Being accepted into a community, valued as a person with stories to share, can provide a true ray of hope in someone’s otherwise dark, lonely, and hopeless life.

The teens in this parish’s [St. Peter’s] Journey to Adulthood ( J2A) youth group know this already. I once asked them on a sleepy Sunday morning, “How can we become people who sacrifice for others?” One teen immediately replied, “By talking to people, getting to know them.” The group agreed that talking with someone is sometimes avoided because of how the person looks or rumors we’ve heard about them. When asked what they need to be able to get students in their schools talking to each other, they decided they need the time, safe space, and chocolate (some kind of tasty food to gather around).

Not long after that J2A meeting, the “Lenten Friends and Faith at Home” groups began. My husband, Andy, and I were blessed to have the chance to offer our small home to an expanded version of the young adults’ Theology on Tap group. For this Lenten series, our group featured those as seasoned as seventy-eight-years-old and as young as twenty-five. The expert prompts of short video clips, Scripture, and questions led to all of us taking risks—sharing our own stories of triumph and growth as well as loss, violence, and struggling to forgive. I saw that the J2A group was entirely correct—given the time, safe space, and chocolate (or a beverage of one’s choice), a group could easily engage with each other and get to know each other on a much deeper level. I found myself choosing to tell personal stories as others listened attentively, also willing to take on others’ pain as I wore their skin for a short time. I had no problem becoming vulnerable in front of this group, and others chose to do the same. Personal growth occurred through listening to others’ stories and wrestling with questions like, “Is every action forgivable?” or working together to brainstorm ways to capture the feeling of gratefulness every morning. Again, I had found that our stories encouraged others to share, to be honest with ourselves, and to forget age or which worship service we attend. We grew in our love for each other and for our model of love, Christ.

The reading from 1 Peter (3:13–22) said, “In your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have.”3 This hope is the love of Christ that the world needs to know about and that we need to share with others. This is also my hope; that we love each other enough to come together as a nation, as a united people, to have an honest discussion about how to protect our citizens—our children—from violence. As I experienced with the ...