1

Meet the Platypus

Truly, platypuses are things of pure wonder. They combine an incredible array of characteristics and behaviours from across the animal kingdom as well as demonstrating qualities that are all but unique among mammals. The platypus has a body like a mole, feet like an otter, hamster-like cheek pouches and horny grinding pads in its mouth instead of teeth, which it uses to mush up insect larvae, crustaceans, worms and occasionally tadpoles and snails. And, most conspicuously, it has a beak, which at first appears almost indistinguishable from that of a duck – and this is why the earliest European settlers in New South Wales called them ‘duck-moles’ or ‘water moles’.

As if all that weren’t astounding enough, these semi-aquatic burrowing mammals lay eggs, but also produce milk – despite having no nipples (an old joke is that platypuses are the only animals that can produce their own custard). They hunt underwater with their eyes closed while sensors in their bills detect the electricity given off by their prey’s beating hearts. Their fur fluoresces under UV light, but we don’t know why (if indeed there is a reason).[1] And the males are venomous. They amaze me.

Since that first trip to Tasmania, I am lucky enough to have met platypuses regularly in Australian creeks and lakes, located in environments ranging from tropical rainforest to alpine tarns. Each instance is etched in my memory with undiluted joy. Combining these encounters on the platypuses’ own terms with closer, unhurried meetings with museum specimens is a way of piecing together all the details of how they live their lives; to see what it means to be a platypus.

*

It’s obvious to the most casual observer that platypus bills are unique: no other mammals have mouths anything like them. Nor does any other animal. The first Westerners to describe the platypus didn’t immediately appreciate that their bills are not actually duck-like as they were working with dried skins sent back to Europe. The bills they encountered were tough and hard, whereas a live platypus’s bill is supple and leathery in texture. Within the bill are thin rods of bone, which act as supports. Looking at their skulls in a museum, I always think that they resemble the tail of a massive earwig, as these rods look like pincers. But the skin that covers them is soft and rubbery.

Platypuses’ bills are equipped with not one, but two sensory systems, which enable them to find food when the other senses have been shut off. Like most other aquatic mammals, platypuses close their nostrils when diving, eliminating smell (however, they do have an olfactory sense organ that opens into their mouth, called the vomeronasal organ, which could possibly be used underwater to detect chemicals given off by prey or the scent glands of other platypuses). In addition, their eyes and ears are positioned in a muscular groove in their skin, which they shut tightly while submerged, so they cannot use sight or sound to navigate or hunt either. (No other mammals pair their ears and eyes in this way – not even their relatives the echidnas.)

Instead, their bills contain mechanosensory cells, which means they are highly sensitive to touch. As is the case with many species of fishes, this may enable them to detect movements in the water that result from animals moving nearby. Their bills also have sensory mucous glands that can detect electric fields. As we are taught in biology classes, every single muscle contraction in the animal kingdom – including every heartbeat – is the result of an electrical signal from the nervous system. When hunting, platypuses scan their heads from side to side, moving them like a metal detectorist. We assume that they are tracking down live food by sensing the electricity being given off by other creatures’ muscles. Sharks and some other fishes do this, too, but this behaviour is almost unheard of in mammals. To date, the only mammals known to be electro-sensitive are platypuses, along with echidnas (although to a much lesser extent, as we shall see) and a single species of dolphin, the Guiana dolphin, from South and Central America.

Only recently, in 1986, did researchers establish these electro-receptive abilities of the platypus, and it was nearly a decade later that scientists worked out that they have this gift in order to catch food.[2] Prior to that, we were left to guess at what enabled the platypus to locate food when three of its ‘traditional’ senses were cut off when underwater – something that was a particular puzzle considering the sheer volume of food they can find: up to half a kilo (one pound) a night. Nevertheless, the bill was always the clear candidate. As Burrell put it in 1927, ‘the muzzle of the platypus is possibly the most remarkable organ for sensory perception found in the Mammalia’.[3] His speculations were on the nose, so to speak: ‘My opinion is that this animal must have developed some extraordinary means of finding its prey, apart from the sense of touch, and that the sensory apparatus through which this acts is connected in some way with the fleshy nature of the bill.’ He called it a ‘sixth sense’, which we now know is the astonishing ability to detect electricity.

As for other senses, platypuses are noteworthy for their lack of whiskers and external ears. Some have cited both of these evolutionary omissions as evidence of the species’ primitivity. However, the fold on their heads in which the ear (and eye) sits – the one that is fastened shut when underwater – is highly muscular, with fine controls. The sides of the groove can contract and dilate rapidly, and ‘point’ at the source of a sound. Much like many other mammal species with mobile ears, it can cock its furrow to act as an external ear. As to the lack of whiskers, it’s true to say that this evolutionary sensory development probably appeared after the ancestors of platypuses and echidnas split off from the rest of the mammals, but I think the electro-receptive adaptation more than makes up for it.

In the early 1830s, one of the first Englishmen to keep captive platypuses alive in Australia long enough to observe their behaviours was a naturalist named George Bennett. He wrote that platypuses would allow their bodies to be stroked, but their bills were so sensitive that the animals darted away if they were touched.[4] Another authority on platypus behaviour, David Fleay, reported that they would head back to their burrows in heavy rain ‘because the drops of water pattering on [their] highly sensitive bill cause acute discomfort’.[5]

Nonetheless, while underwater, platypuses use their bills to rummage around in the gravel, cobbles and mud at the bottom of lakes and rivers in search of their invertebrate prey. Having caught it, their food is then jammed into their cheek pouches until they return to the surface to eat. There, they crush up the contents of their cheek pouches with the ridged, horny pads inside their bills. Adult platypuses don’t have any teeth (three molars appear on each jaw during development but are lost during adolescence), but these horny pads are an excellent adaptation for grinding up the hard exoskeletons of crayfish, shrimp and insect prey, as well as for coping with the heavy wearing effects of the sand and grit that comes with foraging on lake and river bottoms. It seems that in their evolution, platypuses have upgraded their feeding equipment from standard teeth: horny pads can be regrown and replaced constantly, unlike most mammals’ teeth.

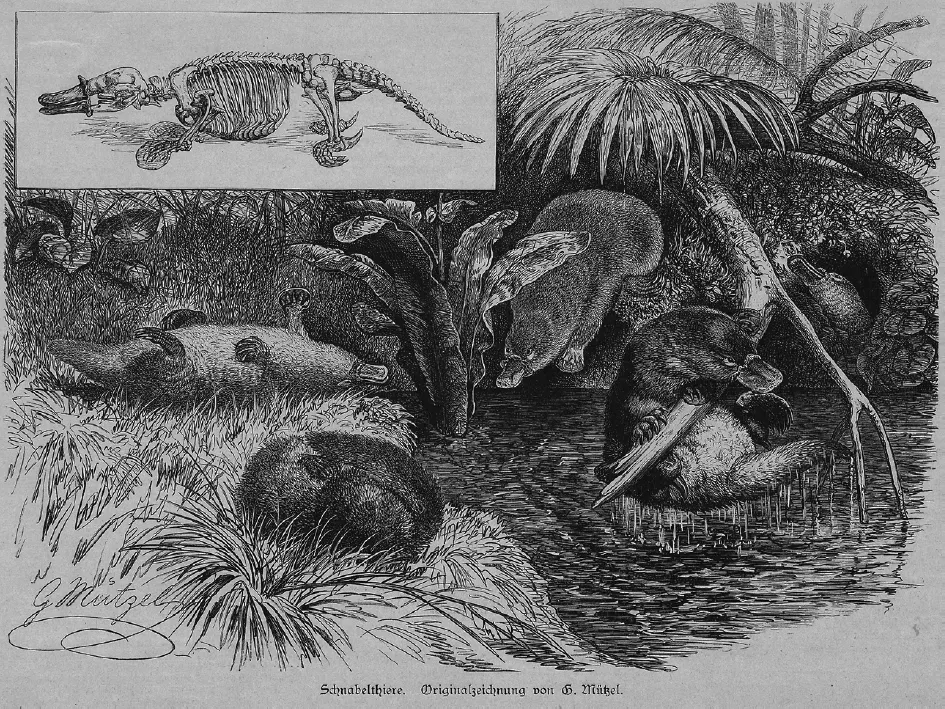

Platypuses doing platypus things – an 1884 print by German artist Gustav Mützel. The skeleton illustration shows the male’s venom spurs on its ankles, and the leathery shield at the bill’s base has dried into an upright position – typical of historic specimens. In life it lays back across the face.

Public domain. Image sourced from Wikimedia Commons

*

Platypuses can live for over twenty years and are found in freshwater habitats across parts of eastern Australia, from Queensland’s steamy tropics to Tasmania’s icy highlands. The platypuses in the north are much smaller than those in the south. For instance, a big Tasmanian male may exceed 60 centimetres (2 feet) in length and weigh in at 3 kilograms (7 pounds), whereas a small male from north Queensland may be barely a third that size. This disparity has probably got something to do with it being a lot colder in Tasmania, because larger bodies lose less heat. Female platypuses tend to be about three-quarters the size of males.

Despite the diversity of climates in which they are found, there is only a single species of platypus, and they have a number of behaviours and other adaptations that allow them to occupy this range. Indeed, many of these traits are effective at buffering temperatures at both ends of the scale. Although they are able to sweat, platypuses can die if the ambient temperature exceeds 30 °C (86 °F), but living in a burrow helps with that as conditions are much more stable underground.

Platypus limbs are rather like Swiss Army knives, with gadgets for walking, swimming and digging. To power their swimming stroke, platypuses use their webbed hands (their hind feet are only partially webbed). No doubt this webbing contributed to their overall perceived ‘duckiness’ and influenced early descriptions, but their webbing is quite different to that of a duck – not to mention the fact that ducks have webbed feet, while platypuses have webbed hands. In ducks, the webs pass between the toes, while in platypuses it passes under their fingers. This web also extends well beyond their digits and creates a fan of skin around the hand that is longer than their fingers. Their front claws curve slightly upwards, creating struts to support the webbing during the conversion of the outstretched hand into a paddle.

When swimming downwards, their hands push out, backwards and then up, so that at the end of the stroke their palms are facing upwards by their bodies. This demonstrates just how supple platypuses are. I’ve tried to replicate this manoeuvre myself, but I can’t make it work within the limits of my human flexibility. For the upstroke to reset, the webbing collapses down as it moves through the water, reducing drag.

Platypuses’ hands look very different on land, however. There, the webbing is folded back into their balled-up fists, to create a more terrestrial ‘foot’ for walking, which they do on their knuckles.

Their foreclaws are also put to use as combs when preening, but they mainly do this with their hind feet. Platypuses are extremely flexible and can contort themselves into all manner of shapes when going about regular platypus business. When grooming, they can reach pretty much every inch of their bodies with the claws on their back feet. Keeping their fur in good condition is important for aquatic mammals, and the soft, dense underfur of the platypus is particularly adept at keeping water out. Even after many hours out foraging, a healthy platypus’s skin doesn’t get wet.

And when digging, they expose their strong claws while the webbing remains tucked away, to act like garden forks cutting into the soil of a riverbank. When you examine a platypus skeleton you can see that their bones have impressive lumps and bumps where large muscles attach, and these give them the strength to create such long burrows.

Burrell believed that the skin of a platypus’s hands would need to remain ‘cool and moist’ to enable this versatility, hinting at constant lubrication – a secretion that foiled one of his less conventional platypus experiments:

Extraordinarily considering their body size, a female platypus can dig a burrow that is more than 10 metres (33 feet) long to keep her young safe – with credible claims of burrows exceeding 30 metres (98 feet). The burrows have numerous twists and turns, with side routes ending in dead ends. Burrows that are simply used for sleeping – dug by both males and females – are shorter. Their entrances are typically a little way above the waterline, concealed among vegetation.

Most accounts of platypus burrows mention that they slope upwards from their entrances on the bank towards the surface of the soil, and then run parallel to it, about 30 centimetres (a foot) or less below ground, without emerging into the open. Platypuses avoid digging into the burrows of rakali (native water rats), rabbits, and other bends in their own circuitous tunnels by a similar distance, tunnelling below or around them, but never breaking through.[7] We have no idea how they know those tunnels are there.

Deep inside its nesting burrow, a female platypus will make the nesting chamber comfortable: she collects wet vegetation and drags it to the nest by pinning it between her hind feet and curled tail. This prevents her eggs and nestlings from drying out.

As well as their hands, their bills are also used heavily in burrowing, loosening the soil with solid muzzling of the ground ahead of them, before they insert their hands into the rubble and pull it back over themselves. All the while, the strongly curved hind claws lock the platypus into position in the walls of the tunnel. As platypus tunnels are more or less the same diameter as the animal, turning around would be a challenge mid-excavation. Instead, they can simply retreat back down the tunnel by swivelling their hind feet into reverse: they can point backwards. As Burrell puts it, ‘It is rather amusing to witness this act, for, at the outset, the fore-parts are usually obliterated with earth, and the tail, which in contour and elevation somewhat resembles the head, sometimes puts one at a loss to guess whether the creature is really coming or going.’ Marvelling at their versatility, he compares their hind feet to the forepaws of a sloth or bear, in that they can form a closed grip as well as performing all this preening and bracing.[8]

*

When you come across any burrow, the shape of the tunnel can give you a good clue about the kind of animal that dug it. Among the most distinctive are scorpion burrows, which look just like an upturned smiling mouth. Their pincers are held outwards and upwards from their bodies, so that’s how they dig. Lizards and tortoises hold their legs out in a sprawling posture, so when they dig their limbs push the soil down the sides of their bodies – this means that, in cross section, their burrows are typically arched: flat on the bottom and curved around the top, like a D turned on its side. In contrast, most mammals hold their limbs directly below their bodies, so most of the soil is pushed more centrally under their torsos as they dig. Their burrows are therefore more rounded in cross section. The animals’ specific body shape can give more detailed pointers, essentially by picturing the overall front-on silhouette of the creature: rabbit and mouse burrows are more or less circular, foxes’ are taller than they are wide and badgers’ are wider than they are tall. When it comes to platypuses, their burrows are roughly oval, or sometimes like the sideways ‘D’, as their legs are held out to the side.

Burrell dug into many burrows and observed countless individuals in the process of forming them in order to provide a detailed account of how they are achieved. Once the platypus has excavated a few inches, it contorts its body to condense the soil down into the tunnel walls and floor, which decreases the chance that they will collapse (they can burrow on their backs and on their sides, and can spin in spirals to tamp the soil down). Very little earth is actually found outside the entrance to platypus tunnels. If soil conditions allow, instead of removing it, it is merely compressed into the walls. There are major energetic advantages to this – 10 metres (33 feet) is a long way to push soil down a tunnel to get it out of the entrance, particularly if you can’t turn around. This strategy also helps to avoid detection by predators, both while digging and subsequently: I have regularly located burrowing marmots from the jets of dirt being flung out behind them as they dig (it’s also clear that they are having to shove this soil behind them in several stages as they travel further down the tunnel); and the spoil heaps around badger burrows are far more conspicuous than the entrances themselves.

With that said, ther...