![]()

1

Introduction:‘Hum Aapke Hain Koun?’ – Cinephilia and Indian Films

Consider a scene from Ram Gopal Varma’s Hindi film Rangeela/Colourful (1995). Muna walks into the film studio to apologise for his uncouth behaviour at the movie theatre the previous evening. He sees Mili practising her dance moves and cannot fathom her stories of studio grandeur emanating from this ordinary, dark space. She rises to his challenge: the lights beam on her, music streams in, and Mili gyrates to ‘Jo mangta hai’/‘What you want’. Dumbstruck, Muna imagines joining Mili in a song and dance sequence that includes a virtual journey through New York and Hyderabad. In short, Muna falls hopelessly in love with Mili. Until this moment, the film insists on a bantering relationship strengthened by their mutual love for films: he is a ticket tout outside Bombay film theatres; she, a chorus girl in a Hindi film. Each is trying to get closer to the magic of cinema. Occurring in the first half of the film, as seasoned viewers of the Hindi film love story, we expect him to run into troubled waters, thus delaying his union with Mili. As he struggles to confess his love, to get what he wants (jo mangta hai), a triangular economy of desire unfolds: the hero of the film within the film, Kamal, also falls in love with Mili when he watches her practise dance on the beach. Unlike Muna, Kamal is motivated in his desire for Mili by her exuberance outside the studio. In a fortunate turn of events, Kamal recommends Mili to replace the heroine in his film. They finally produce their film, and the audience declares Kamal and Mili a successful pair on the screen. Intimidated by their success, Muna flees Bombay, assuming that Mili’s rise to stardom squeezes him out of her life. However, Mili, with Kamal’s help, tracks him down. In the final moments of the film, she confesses her love for Muna.

Their union remains credible within the film’s own internal logic favouring cinephilia over film-making, a preference dictating the difference between Muna’s and Kamal’s desire for Mili. Even as the film struggles to preserve Muna’s love as independent of Mili’s meteoric rise to stardom, we know that it orchestrated his love from the point of view of a film-going fan, a cinephile, and only later as somebody outside the play of light and sound. He falls in love with Mili’s image in the studio, the film star, not his pal on the streets. Mili, on the other hand, expresses her desire only at the very end of the film, but her unstated reasons and indecisiveness drive the narrative logic of the love story. In other words, we wait eagerly for Mili to decide between her star-struck devotion for Kamal and her love for films that leads her to Muna. The film implies that Kamal loses because of his inability to participate in the correct triangulation – he loves only Mili, whereas Mili’s first love is the cinema. It is Muna and Mili’s love for cinema that dictates their love story, the preferred triangulation in the film.1

Rangeela, like Varma’s other films, summons cinephilia, reminding us that both film-makers and viewers share complicity – their films can ‘read’ our desire as much as we can marshal our critical machinery to read their creations. Obviously, Rangeela is not a first in this genre: Ketan Mehta’s comic film Hero Hiralal (1988) revolves around an auto rickshaw driver’s obsession with a film star; casting Kamal Haasan in four different roles, Singeetham Srinivasa Rao’s Tamil film Michael Madan Kama Rajan (1990) plays with thematic and visual conventions in Tamil cinema; and Ram Gopal Varma’s Daud/Run (1997) uses the caper to highlight the frustrations of a hermeneutic reading of Indian popular films. Reading back our insights to us, analysing stereotypical endings and stock details, these films showcase a cinema that can confidently parody its own conditions of production while fine-tuning certain genre tendencies. Parading conventions as comic interventions – the wet sari, the sad and loving mother, song and dance sequences – each of these films strikes an ironic posture that, as critics, we are reluctant to accord the commercial industry. Even Sooraj Barjatya’s Hindi film Hum Aapke Hain Koun..!/Who Am I to You..! (1994), a smash hit advertising itself as wholesome family entertainment with fourteen songs, does not shy away from a comment on spectatorship.2 The opening credit sequence has both leads, Madhuri Dixit and Salman Khan, looking straight at us and singing ‘Hum aapke hain koun?’/‘Who am I to you?’; asking us to reflect on our relationship to cinema, the film draws us into a triangular economy of desire, making us an integral part of its love story.3

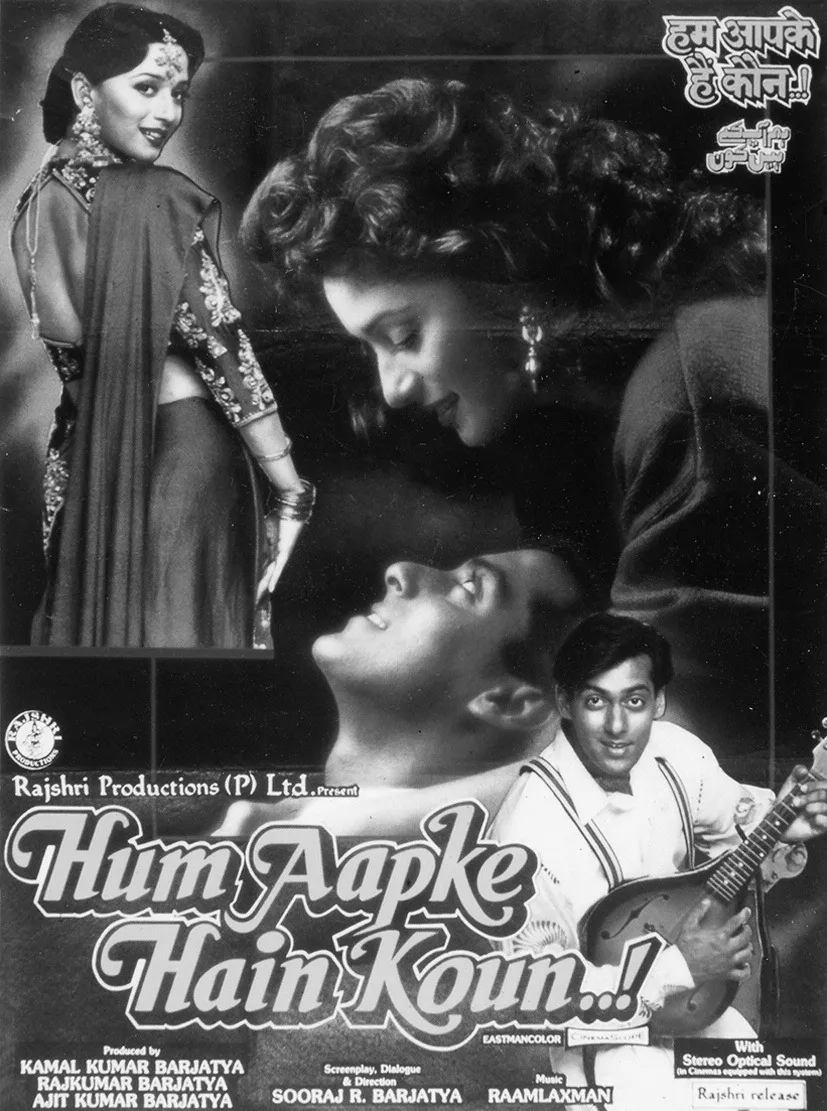

Poster for Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (courtesy of the National Film Archive, Pune)

We can fully appreciate the verve of these films if we recall that in each filmic instance they maintain a respectful distance from Indian cinema’s tragic tale of film-making narrated in Guru Dutt’s Kagaz Ke Phool (1959), in which the hero as film director suffers a tortured relationship to both film-making and love. Dutt’s film interpolates us as voyeurs looking at the unfolding narrative of doom, a relationship to the screen ideally suited to reaffirming the negative potential of cinema. In sharp contrast, the playful and ironic commentary on film-making cited in the above films depends on our familiarity with cinematic conventions, familiarity cultivated through our long relationship with Indian popular cinema. More often than not, by calling attention to our viewing habits within the diegesis and naming it love, contemporary Indian films have closed the gap between the screen and spectator. Whether or not we accede to the proposal of love and familiarity from the screen, these films signify a confidence in film-making we have not been privy to for the past twenty-five years.

This confidence signals changes in aesthetic, technical, and reception conditions, simultaneously nudging us to acknowledge a shift in our critical engagement with cinema. To account for the changing conditions of production and conditions satisfactorily, between the screen and the spectator, we should read popular Indian films from the point of view of a cinephiliac, one that is based on an ambivalent relationship to cinema: love and hate.

Whereas cinephilia colours the selection of genre films in this book, the task of this introductory chapter is to map the theoretical and methodological issues implicit in my reading of films. Starting with the place of cinephilia in film theory, I move to consider the different changes in production and reception of Indian films, both locally and globally, that inspire the love of this cinema. Encouraged by its ability to entertain beyond national boundaries, this book places popular Indian cinema within a global system of popular cinema to account for its simultaneous tendency to assert national and local cinematic conventions, and also to abide by dominant genre principles.

Identifying the strength of certain conventions unique to Indian cinema as a constellation of interruptions allows us to consider national styles of film-making even as Hollywood films assert their global dominance. By bearing in mind this constellation of interruptions, we should reconsider the direct importation of film theory as ideal reading strategies for Indian films, even though they have been productive in understanding the structure of pleasure and anticipation of Hollywood genre films. The introduction, in short, suggests that, just as popular Indian films rewrite certain dominant genre principles, film theory, too, needs to undergo revisions in order to read adequately the different structuring of anticipation and pleasure in this cinema that also has a global application and circulation.

Even the most casual tourist in India resorts to hyperbole to describe the potency of this cinema that produces a thousand films in more than twelve languages each year. For instance, in his travelogue Video Nights in Kathmandu, Pico Iyer declares in a significant synecdoche that spills over its own rhetoric, ‘Indian movies were India, only more so.’4 Other writers, such as Salman Rushdie, Alan Sealy, and Farrukh Dhondy, have used various aspects of Indian film culture to spin fabulous narratives of success and failure, stardom and political life, love and villainy.5 For the uninitiated, most commentators will list implausible twists and turns in plots, excessive melodrama, loud song and dance sequences, and lengthy narrative as having tremendous mass appeal, but little critical value. However, the films cited above belie such judgments and are symptoms of seismic changes between cinema and society that have seeped into the ways in which we read, think, and write about Indian cinema, thus initiating our love affair with it.

However expansive the influence of cinema, Indian film-makers are acutely aware that most films fail at the box office. Their financial anxieties have increased in recent years with the rise of adjacent entertainment industries that threaten to diminish the power of films, even if cinema as an institution is not waning in the public imagination. Trade papers from the 1980s record the industry’s fears of the growing video industry that many believed would eventually discourage audiences from going to theatres. Nevertheless, the arrival of video shops in India also exposed the film-going public to world cinemas, an opportunity previously afforded only by film festivals and film societies. Suddenly films from other parts of Asia, Europe, and America were easily available to the film buff. Film-makers were also very much part of this video-watching public, freely quoting and borrowing cinematic styles: for instance, director Ram Gopal Varma started his career as a video-shop owner. While a section of the urban rich retreated to their homes, trade papers reported an increase in film attendance in small towns and villages. Instead of assuming that one mode of watching would give way to the next evolutionary stage, we now find films coexisting alongside a robust video economy and satellite or cable television. Ironically, both cable television and video shops are also responsible for creating nostalgia for older films. Together, these different visual media have changed reception conditions by generating an audience that has developed a taste for global-style action films while simultaneously a cherishing a fondness for the particularities of Indian cinema.

In addition to video and satellite saturation of the visual field, American films (sometimes dubbed in Hindi) started reappearing in Indian theatres after a new agreement was signed between the Government of India and Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, Inc. (MPPDA) in April 1985, ending the trade embargo that began in 1971.6 Initially, Indian film-makers protested against this invasion, but slowly reconciled themselves to their presence after recognising that American films did not pose a threat to Indian film distribution.7 Occasionally we find characters in Indian films taking potshots at American cinema: in Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya (1998), protagonists purposely misread Jurassic Park (1993) as a horror film starring lizards; in Tamil films, cross-linguistic puns abound around James Cameron’s Titanic (1997). These playful engagements with American culture confidently acknowledge that Indian cinema audiences belong to a virtual global economy where films from differ...