![]()

1

Historical Background to the Postexilic Prophets

1.1 The Theological Expectations Arising from the Exile

Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi are addressed to those living in Jerusalem in the early Persian period. Although written to the situation after the return from exile, these books cannot be properly understood apart from the theological expectations shaped by the exile. Not everyone had been taken into captivity (Barstad 1996), but the future hopes for the people of God rested with those who had been taken, not those who had remained (cf. Jeremiah 24).

There are ongoing debates about whether the formative period for the biblical texts was preexilic (e.g., Schniedewind 2004), exilic (e.g., Albertz 2003), Persian (e.g., Davies 1992, 1998), or Hellenistic (Lemche 1993). This study guide assumes that, by the end of the exile, it is likely that many of the elements of what we now know as the Hebrew Bible were beginning to take shape. This would have included (some form of) the Pentateuch, a version of what scholars call the Deuteronomistic History (a theologically shaped history that explains Israel’s possession of the land as a term of God’s covenant with them and expulsion from the land as the result of their covenant unfaithfulness), a collection of psalms shaped by similar themes, and a corpus of prophetic works that pronounced Yahweh’s judgment on sin and promised hope beyond the judgment of exile. (This is a reasonable assumption, given the many allusions to such texts that appear in Haggai and Zechariah 1–8.)

The following passages provide a sample of these key themes.

• Deut. 29:9–30:10 (the terms of God’s covenant with Israel)

• 2 Kgs 24:1-4, 18-20 (exile because of covenant unfaithfulness)

• Lamentations 3 (a “theological” account of the experience of exile)

• Jer. 30:1-22 (the promise of restoration after exile)

As a result, there was a theologically driven expectation that the exile would eventually come to an end, which Yahweh would bring his people back to their land and that there would be a restoration of all that had been lost—a rebuilt Jerusalem, a reconstituted priesthood, a reconstructed temple, and a reestablishment of the Davidic monarchy. Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi address, in different ways, those whose experience of return failed to live up to their expectations of the glorious restoration envisaged in the prophets.

1.2 A Caveat about Sources and Unresolved Historical Questions

The following account of the history of the postexilic period has been reconstructed from a variety of sources. There are tensions (and in some cases inconsistencies) between data from documentary sources (both biblical and extra-biblical) and archaeological data.

There is an ongoing debate between what has been dubbed a “maximalist” approach (which presumes the historical veracity of the biblical texts, unless proven otherwise) and a “minimalist” approach (which presumes the historical unreliability of biblical texts, unless independently confirmed). This study guide will seek to take a middle path, by using the documentary sources to reconstruct a history, while at the same time highlighting the key tensions and unresolved historical questions.

On the reliability of Ezra-Nehemiah as a historical source, see Williamson (1983, 1985:xxviii–xxxii) for one view and Grabbe (2006) for the counterview. For a summary of the tensions between Ezra-Nehemiah and a historical reconstruction, see Grabbe (2015).

1.3 Under Persian (Achaemenid) Rule

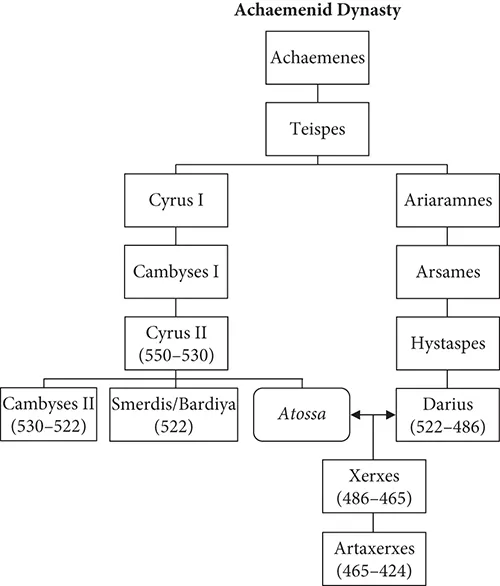

The military conquests of Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great) established the Persian (Achaemenid) Empire. The Achaemenid Empire takes its name from Achaemenes, who was (according to Darius) the common ancestor of both Cyrus the Great and Darius (see Figure 1.1 for the family tree of the Achaemenid dynasty).

Figure 1.1 The Achaemenid dynasty

Cyrus the Great rose to prominence around 550 BCE, after defeating the Medes and winning a series of victories over Babylonian forces in Asia Minor. After routing the Babylonian army at Opis, Cyrus was able to capture the city of Babylon largely unopposed in October 539 BCE (Briant 2002:41–4).

Cyrus’s victory is celebrated in a cuneiform tablet known as the Cyrus Cylinder, which attributes the defeat of the Babylonian king Nabonidus to the judgment of Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon. Lines 28–33 describe how Cyrus restored the cultic items that had been captured by Babylon to their native temples and returned captives to their native lands, directing that prayers be offered for Cyrus. The message on the cylinder is focused to the East of the Tigris River, and as such the Jewish people and religion are not explicitly referenced. However, the policy of repatriation and recommissioning of worship at local temples is broadly consistent with the terms of Cyrus’s edict as recorded in the Hebrew Bible (cf. Briant 2002:46–8).

Cyrus receives positive treatment in the biblical texts. He is described as Yahweh’s anointed in Isa. 45:1, and accounts of his edict are recorded in Ezra 1:1-4, 6:1-5, and 2 Chron. 36:22-23. In the biblical account, Cyrus is integral to Yahweh’s plan to bring his people back “when the 70 years of Babylon are complete” (Jer. 29:1-14, cf. Isa. 44:28).

1.4 The First Return under Sheshbazzar

In response to Cyrus’s edict in 538 BCE, a first wave of Israelites returned to Jerusalem. According to Ezra 1:5, this group was under the leadership of Sheshbazzar, who is described as “the prince of Judah” and comprised the “family heads of Judah and Benjamin and the priests and Levites.” The retrospective account of this period in Ezra 5:14-16 indicates that Cyrus had appointed Sheshbazzar as governor (perhaps a Neo-Babylonian carryover appointment—see Silverman 2015), given him articles of gold and silver that had been taken from the Jerusalem temple, and commissioned him to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem.

Scholars are divided over how to correlate the historical data in Ezra 1–6 with Haggai and Zechariah. This study guide follows Williamson (1983:16–20) and interprets Ezra 1 as describing the first wave of returnees under Sheshbazzar after Cyrus’s edict in 539 BCE (about which Ezra 5:13-17 provides an historical retrospect), and Ezra 2–6 as describing the activities of a second wave of returnees led by Zerubbabel and Joshua, who are active in Jerusalem early in the reign of Darius, and thus that the refounding described in Ezra 3:10-13 is the same event alluded to in Hag. 2:18. Ezra 4:6-24 interrupts the chronological sequence by recounting stories of later opposition in order to demonstrate that the resistance to rebuilding the temple was also later manifest in opposition to the rebuilding of the walls and city of Jerusalem.

Haggai and Zechariah 1–8 make no reference to a prior laying of the temple’s foundations in the time of Sheshbazzar (cf. Ezra 5:16). Work on the temple evidently did not progress very much between 538 and 520 BCE, because Hag. 1:4 (c. 520 BCE) describes the house of Yahweh as still being a “desolation.”

It is not clear how large either contingent of returnees was. Although there are divergent views (e.g., Hill 2012:33), the view taken here is that the list of returnees in Ezra 2 relates to a second contingent who returned circa 520 BCE with Zerubbabel and Joshua (or perhaps the total of both contingents).

Either way, the number of the returnees in Ezra 2 (c. 50,000) is in tension with archaeological population estimates, which indicate that the entire population of Judah in the early Persian period was no more than 30,000, with the initial population in Jerusalem up to 3,000 persons (Grabbe 2015:294–5, cf. Carter 1999).

1.5 The Rise of Darius

There was considerable political turmoil surrounding the rise of Darius in the two years immediately preceding the recommencement of work on the Jerusalem temple in 520 BCE. One source of information about this is the Behistun Inscription. The Behistun Inscription is a massive stone relief and accompanying text in three languages, which Darius had carved on a cliff face of Mount Behistun in Western Iran. According to Darius’s account in the inscription, Cambyses, the son of Cyrus II, who ruled from Cyrus’s death in 530 BCE, secretly killed his brother Smerdis, also known as Bardiya. In March 522 BCE, a man named Gaumâta led a revolt, claiming to be Smerdis, the brother of Cambyses. Gaumâta/Smerdis seized the control of the kingdom from Cambyses, who then died of natural causes. In September 522 BCE, Darius overthrew and killed Gaumâta/Smerdis and became king. The accession of Darius occurred in late 522 BCE—perhaps December 22, though see Edelman (2005:99–103) for other options.

Darius spent the next year fighting nineteen battles to quell revolts in a number of provinces. There were also subsequent rebellions by the Elamites (c. 521 BCE) and Scythians (c. 520 BCE), which he also successfully put down. By around 520 BCE, Darius was the undisputed ruler of the Persian Empire.

In the Behistun Inscription, Darius traces his ancestry back to Achaemenes, whom he identifies as the founder of a royal dynasty that included Cyrus and Cambyses. The inscription depicts Darius’s rise to the throne as a reestablishment of the kingdom that had been stolen by a usurper. Darius reinforced his claim to the throne by marrying Atossa, who was both a daughter of Cyrus and the wife of Cambyses (Herodotus, Hist, 3.88), and she bore him a son, Xerxes.

Darius describes himself as a restorer: “I restored that which had been taken away, as it was in the days of old” (Behistun line 14). He describes how he restored the kingdom, restored temples destroyed by Gaumâta, and restored people to their lands. This depiction is consistent with the account of Darius in Ezra 6:1-12.

1.6 “Yehud” under Persian Administration

According to Herodotus, the Greek historian, Darius reconfigured the Persian Empire into twenty satrapies (Hist 3.89). The fifth satrapy was “Beyond the River” (ebir-nāri), covering the region west of the Euphrates, including Syria and Palestine (Hist 3.91). Ezra 5:3 identifies the governor of “Beyond the River” at this time as Tattenai (who appears in cuneiform sources as Tattannu—see Rainey 1969).

“Yehud” (the Aramaic name for Judah) was a tiny sub-province of “Beyond the River” with a Persian-appointed local governor. We have only limited information about these governors. Only three are identified by name in biblical sources—Sheshbazzar, the first governor at the time of Cyrus; Zerubbabel, who was governor at the time of Darius (Hag. 1:1); and Nehemiah, who was governor during the reign of Artaxerxes I (see §1.8).

To fill in the gap between Zerubbabel and Nehemiah, Meyers and Meyers (1987:14) use bullae and seals from the early Persian period to recreate the following succession of governors of Yehud.

* Zerubbabel (520–510?)

* Elnathan (510–490?), whose wife was Shelomith, daughter of Zerubbabel

* Yeho’ezer (490–470?)

* Ahzai (470–?)

* Nehemiah (445–433)

1.7 The Situation in Judah in 520 BCE

The year 520 BCE is the immediate context for the prophetic ministry of Haggai and Zechariah (see §2.1 and §3.1). The community were under the leadership of Zerubbabel and Joshua and had been experiencing drought and scarcity for some time (Hag. 1:6, 9-11, cf. Zech. 8:10-12).

Zerubbabel was the Persian-appointed governor of Judah at this time. Zerubbabel was the grandson of Jehoiachin, the king of Judah at the time of the exile (1 Chron. 3:19). However, unraveling the ancestry of Zerubbabel is complex. Zerubbabel is described as the “son of Shealtiel” in Hag. 1:1, 1:12-14, 2:3, 2:23; Ezra 3:2, 3:8, 5:2; and Neh. 12:1. However, in 1 Chron. 3:17-19, “Shealtiel, the son of Jehoiachin” is listed with no offspring, and instead, Zerubbabel is listed as the first son of Pedaiah, the brother of Shealtiel. The most reasonable explanations for this involve either levirate marriage or adoption. The uncertainties are compounded because the command of Jer. 22:30 to “record this man (Jehoiachin) as if childless” may have had particular implications for a genealogy traced through him.

Joshua (also spelled Jeshua) was the High Priest (lit. “Great Priest”) at the time of Zerubbabel. Joshua was the son of Jehozadak (also spelled Jozadak), and grandson of Seraiah, the chief priest at the time of the exile (2 Kgs 25:18, 1 Chron. 6:15). Both Joshua and Zerubababel are central figures in the biblical accounts of the rebuilding of the temple (Haggai 1–2, Zechariah 3–6, Ezra 2–5). On the role of the priesthood in this period, see further Boda (2012), Grabbe (2016), and Redditt (2016).

The consensus view (based on Ezra 6:15) is that the rebuilding of the temple was completed in 515 BCE (contra Grabbe 2015:305, who argues that it was not finished until around 500 BCE, and Edelman 2005, who argues for a redating of the temple-building project to the reign of Artaxerxes I).

1.8 Fifth Century BCE—Darius, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes

Whereas the events around 520 BCE are the c...