![]()

1

Shakespeare on European festival stages: An introduction

Paul Prescott, Nicoleta Cinpoeş and Florence March

Dear Reader: you have before you a travel companion, the first of its kind. This book will take you across continental Europe offering an introduction to each of the festival stages that have illuminated the works of William Shakespeare over the last seventy or so years. You will travel across the length and breadth of the continent: from the (mostly) balmy south to the (often) chilly north, from the planes of central Spain, to the Rhodope Mountains of southwest Bulgaria, to the sea-swept Baltic settings of Gdańsk and of ‘Hamlet’s’ castle in Helsingør, Denmark. You will see the widest imaginable variety of theatrical and artistic offering on a range of stages, from castles, parks and historic theatres to black box spaces, streets and bars. You will hear the works of Shakespeare spoken in many European tongues and in languages from far beyond the continent’s borders. In short, you have here an analytical map for a Shakespearean Grand Tour. Unlike its eighteenth-century antecedent, this Grand Tour is not devoted to the consumption of ancient and enduring monuments of lost cultures and empires. Rather it is a Grand Tour of the exquisitely ephemeral, a journey to sample fashions, trends and innovations in theatre-making as mediated through the lingua franca of live Shakespearean performance.

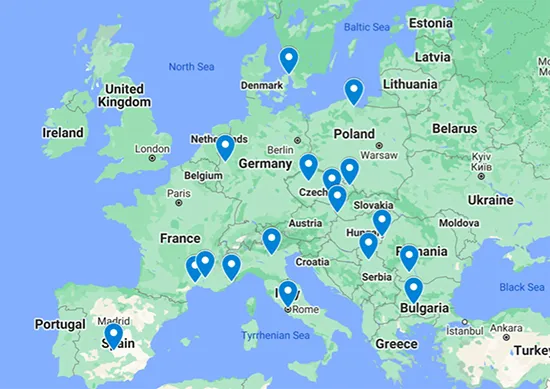

FIGURE 1.1 A map of European Shakespeare festivals in 2020.

Preparations for this book began some years ago when, noting the relative paucity of literature on European Shakespeare festivals, the editors held a sequence of seminars on the theme in Paris, Montpellier, Worcester and elsewhere, often at the biennial conferences of the European Shakespeare Research Association (ESRA). These seminars were rich and stimulating in their own right, but also enabled us to identify the resident experts on each of the fourteen festivals featured in this book and commission the following chapters. These chapters are written by scholars who have long-standing relationships with their respective festivals, sometimes as critics or dramaturges or advisors. They write with insight, expertise and local knowledge. A researcher in live arts is first and foremost a lover of performance, although fascinated spectating and distanced analysis may a priori seem two stances that are difficult to reconcile. The spectator’s pleasure sets off the researcher’s desire to work on the performance, which means overcoming fascination (or at least suspending it) to adopt a critical distance. The paradox is certainly one of the difficulties the researcher in performance studies must learn to deal with. In some cases, the spectator’s frustration may turn out to be the researcher’s good fortune. Failure to fulfil the spectator’s desire and meet his or her expectations can provide an analytic counterpoint to study the creative process at work in a theatrical performance. These dialectics between proximity and distance, love and alienation, play out in the following pages. Equally, given the anti-festive pandemic context in which the book was completed, a year of loss and longing and theatre closures, it is perhaps unsurprising that our authors err more towards celebration than critique.

For much of its recent history, the continent of Europe has been preoccupied with the fraught challenge of forging a peaceable consensus in the wake of the catastrophic first half of the twentieth century. Such a cooperative understanding – especially in the context of the growth of what we now call the European Union – depended on the identification and ratification of shared norms, values and definitions. In an analogous spirit of norm-setting and transparency, we will use this introduction to define each of the keywords in the book’s title and in doing so offer previews of the places to which each chapter will take us.

Shakespeare

When faced with the challenge to define ‘Shakespeare’ in a previous work on European Shakespeare, Balz Engler asked ‘Does the term refer to a person, to a set of printed texts, to a cultural icon, to a theatrical tradition, or to a combination of all of these?’ (2003: 27). The ‘Shakespeare’ in the following pages has little to do with the historical person and everything to do with the ways in which the printed texts ascribed to that person have been theatrically staged in European festivals devoted in part or in whole to those works. Writing in the same volume as Engler at the turn of the millennium, Angel-Luis Pujante and Ton Hoenselaars described a long historical shift of critical perspective – a shift that their own work greatly encouraged – that had served effectively to decentre what they called ‘English Shakespeare’. After this shift, ‘it was no longer necessary to regard translations or foreign Shakespeare performances as adaptations or fallings off from the native stock’; Shakespeare was rather ‘a quarry for a pan-European lexis or collection of myths’ (2003: 24).

It is notable that contributors to this book do not refer with any frequency to the UK or Great Britain. The Shakespeare found here is both pan-European and post-English, a truly globalized phenomenon, floating across cultures and largely untethered to its point of origin. The works have been performed and celebrated for so many decades and even centuries in these continental European locations that the nationality of the author appears to have become almost irrelevant. One of the editors is here reminded of an informal conversation they had with Carlos Cedran, an eminent theatre-maker in Cuba: ‘Shakespeare isn’t English; Shakespeare is theatre.’ Across continental Europe ‘Shakespeare’ also acts as a relatively uncomplicated, post-national umbrella under which to gather theatre-makers from different countries and cultures.

As you will also see in the following chapters, ‘Shakespeare’-making happens differently from festival to festival. In the case of the Four Castles Shakespeare Festival in Prague, Brno, Ostrava and Bratislava, ‘Shakespeare’ signifies native, open-air productions performed in Czech and sometimes Slovak translations. In the cases of the festivals at Gyula (Hungary), Gdańsk (Poland), Craiova (Romania) and Neuss (Germany), ‘Shakespeare’ signifies a range of international, polyglot productions often curated according to a theme or focused on multiple versions of the same text. At the Almagro Festival in central Spain, ‘Shakespeare’ is not the raison d’être for the festival and indeed is barely mentioned on the festival website, so ‘Shakespeare’ means one playwright among many in the European (but specifically Iberian) ‘Golden Age’. In the small village of Patalenitsa in Bulgaria, ‘Shakespeare’ means community theatre made for and mostly by the residents of this remarkable location. In southern France, at festivals in Avignon, Nice and Montpellier, ‘Shakespeare’ has long connoted a humanist model for an inclusive, democratic theatre, a catalyst for social cohesion, ‘a theatre that trusts in man’, according to Roland Barthes (1954: 430–1).

Shakespeare/European

As Tony Judt points out, Europe isn’t really a geographic continent, ‘just a subcontinental annexe to Asia’ (2005: xiii). Our focus is on Shakespeare festivals based on this subcontinental land mass. There is no place for the UK or its variety of Shakespeare festivals in this definition of ‘European’, although British practitioners and companies do figure in the history of some of the continental festivals featured here. It might be tempting to view our choice to exclude the UK through the prism of Brexit: if a slim majority of UK citizens voted in 2016 to take the UK ‘out’ of Europe, who are we to deny the will of the people (or those people of their particular Anglo-nationalist Will)? More pertinently, though, we felt that a single chapter on Shakespeare festivals in the UK could offer only a superficial account, ranging, as it would have to do, from David Garrick’s Stratford Jubilee to the present day. Furthermore, this book is structured chronologically and this would have meant opening with the UK chapter, thus setting exactly the wrong tone for a book that wishes to decentre ‘English Shakespeare’.

Geopolitics and theatre history ask a common question: ‘Who’s in and who’s out?’ In selecting our festivals, we have tried to include every major extant festival at the time of writing. Some smaller, shorter festivals have not made the cut. These include the Bitola Shakespeare Festival (Macedonia) and Shakespeare in Catalonia, both of which run for roughly one week and are – at the time of writing – either still in an embryonic stage of development or (in the case of Shakespeare in Catalonia, 2003–15) apparently suspended or defunct. Shakespeare in Turkey and the Armenian Shakespeare Festival are both of great interest but perhaps belong to a book more closely focused on Shakespeare production and reception in Eurasia. We considered a chapter on the Dubrovnik Festival (founded 1950) which, although not a Shakespearean festival per se, has had a tendency to stage Hamlet in Lovrjenac Castle in fits and bursts over the last seventy years. As Ivan Lupić writes, ‘It is as if the Festival gets tired of Hamlet, but cannot live without Hamlet’ (2014).

In the event, this book covers nearly every active member festival of the European Shakespeare Festivals Network, which was founded in 2010 in order to help festivals ‘exchange information and experience, participate in common projects, and mutually inspire each other for future ventures’ (‘ESFN’ 2021). Although the ESFN currently contains two UK institutions, the York Shakespeare Festival and Shakespeare’s Globe (the latter of which is not really a ‘festival’, given its year-round activities), the vast majority of members are based in Continental Europe, and the contents of this book reflects that preponderance.

Shakespeare/European/Festival

In a fascinating chapter in The Cambridge Companion to International Theatre Festivals, Ric Knowles describes a range of non-European Indigenous festivals as valuable ‘alternative origin [stories]’ that might help us to ‘consider festivals as sites of exchange rather than the commodification of cultures … as being grounded in the land and in Indigenous knowledge systems rather than in the deterritorializing and decontextualizing programming practices of most contemporary Western festivals’ (2020: 72). ‘Indigenous “festivals”’, Knowles suggests, ‘have always been about learning how to share territory and resources – how to live together “in a good way”’ (73).

Such small-scale, localized festivals do indeed offer an attractive model for the future, especially in the present contexts of the climate emergency and global pandemic. But ‘living together “in a good way”’ is not something Europeans have been very good at for most of the last few centuries and what we might call the European Festival Model is clearly a response to that grim fact. As Erika Fischer-Lichte has argued, Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival was conceived in the wake of the failed proto-democratic revolution of 1848/9. The later and equally influential model of the Salzburg Festival can only be understood in the context of the First World War with its co-founder Max Reinhardt viewing the Festival as ‘a peace mission’ and as a ‘place of pilgrimage … for the innumerable people who long to be redeemed through art following the bloody atrocities’ (2020: 89). The number of Europeans who accepted the peace mission offered at Salzburg was wholly insufficient to prevent another war, after which a ruined continent in need of physical and moral reconstruction chose to put its faith in planning, which Tony Judt has described as ‘the unofficial religion of postwar Europe’ (2005: 66f.). The postwar creation of welfare states meant planned housing, education, health care and transport by interventionist governments, but it also meant planned culture, with the rise of international festivals in particular as one component of the premeditated manufacture of civility. One of the chief architects of postwar Europe, Jean Monnet, reflected: ‘Si c’était à refaire, je commencerais par la culture’ (qtd in Judt 2005: 701), implying that culture might have been even more central to continental reconstruction than it was. And yet it did indeed play a major role in shaping a post-nationalist vision of an imagined community. As Karen Zaiontz has argued:

International festivals attempted to repair and, to a certain extent, repress the image of the nation as a generator of far-right populism. The emphasis on ‘masterpieces’ was an attempt to swerve towards more official, elite forms of nationalism, which also made claims to universalism, and away from the kind of populist nationalism that defined territorial sovereignty in terms of ethnic purity.

(Zaiontz 2020: 15)

Of the festivals featured in this book, only the Avignon Festival and the ‘Festivo Shakespeariano’ in Verona date from this immediate postwar period, but many still share the model of reparative festivity and its logic of benevolent cultural exchange. The resistance to the cult of ‘ethnic purity’, for example, was very clearly an impetus for many post-1989 festivals: the Craiova Shakespeare Festival has always embraced Romanian-, Hungarian- and German-speaking theatres from across Romania, while the Shakespeare Festival in (bilingual) Gdańsk often hosts productions from, for example, Lithuania and Germany that draw attention to the city’s complex and richly ‘impure’ pasts. While embracing difference, however, these and other festivals also gesture towards a proto-utopian humanism, one in which, as Hugh Grady has written:

Shakespeare is presented as a democratic, international, universally available, free good that takes its place in and for an imagined community. Such a community consists of social beings untrammelled by inequality or social conflict, taking pleasure in universal narratives that affirm the desired continuity of love and courage as a means to a happier world.

(2001: 26)

Along with Avignon, the key example here is Edinburgh International Festival, also founded in the aftermath of the Second World War, in August 1947, only a few weeks before the Avignon Festival and with a production of the very same play by Shakespeare: Richard II. In October 2006, Jonathan Mills, the newly appointed director of the Edinburgh International Festival, gave the Sir William Gillies Lecture at the Royal Scottish Academy and reflected that:

The Edinburgh International Festival owes its origins to the urgent imperative to rebuild a sense of community in a continent that had been torn apart by the tragedy of World War II; to restore faith, to heal the heartache of shattered lives through music, opera, drama, dance, literature, painting; to pick up the fragments of a civilisation shaken to its core by the atrocities of Leningrad or Auschwitz. In the words of John Falconer, Lord Provost at the time, it was to be a festival whose ambition was to ‘embrace the world’.

(‘EIF’ 2014)

This optimistic vision of the healing and peace-making capacity of culture is hardwired into the ethos of festivity and continues to underwrite the philosophy of Shakespeare festival-makers across Europe. In advertising their 2019 season, Ilina Chorevska and Ivan Jerchikj, the artistic directors of the Bitola Shakespeare Festival in Macedonia, invited their audiences to:

Imagine the world and humanity came to an end, all our civilization, as we know it today […] it’s supposed [i.e. ‘we suggest’] that it could be rebuilt and reconstructed solely based on the works of William Shakespeare.

(Chorevska and Jerchikj 2019)

As with Western Europe after the Second World War, so with the former Soviet bloc of Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Empire in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It is striking that almost half the festivals featured in this book are based in former Soviet bloc countries. Here the paradigmatic case is that of president-playwright Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia in 1990. As we learn in Filip Krajník and Eva Kyselová’s chapter, one of Havel’s first acts on becoming president was to commission Shakespearean performances in the grounds of Prague Castle as part of a wider agenda to reform the civic foundations of a fledgling democracy. In his memoir Disturbing the Peace, Havel wrote:

theatre doesn’t have to be just a factory for the production of plays or, if you like, a mechanical sum of its plays, directors, actors, ticket-sellers, auditoriums and audiences; it must be something more: a living spiritual and intellectual focus, a place for social self-awareness, a vanishing point where all the lines of force of the age meet, a seismograph of the times, a space, an area of freedom, an instrument of human liberation.

(1991: 40)

Krajník and Kyselová link the formation of the Four Castles Sha...