During the course of the twentieth century a wide range of American photographers made images of jazz musicians. Like many of their predecessors, these photographers were preoccupied with the reality of the American experience, the land, culture, and the myths that defined America.1 Jazz was central to their experience.

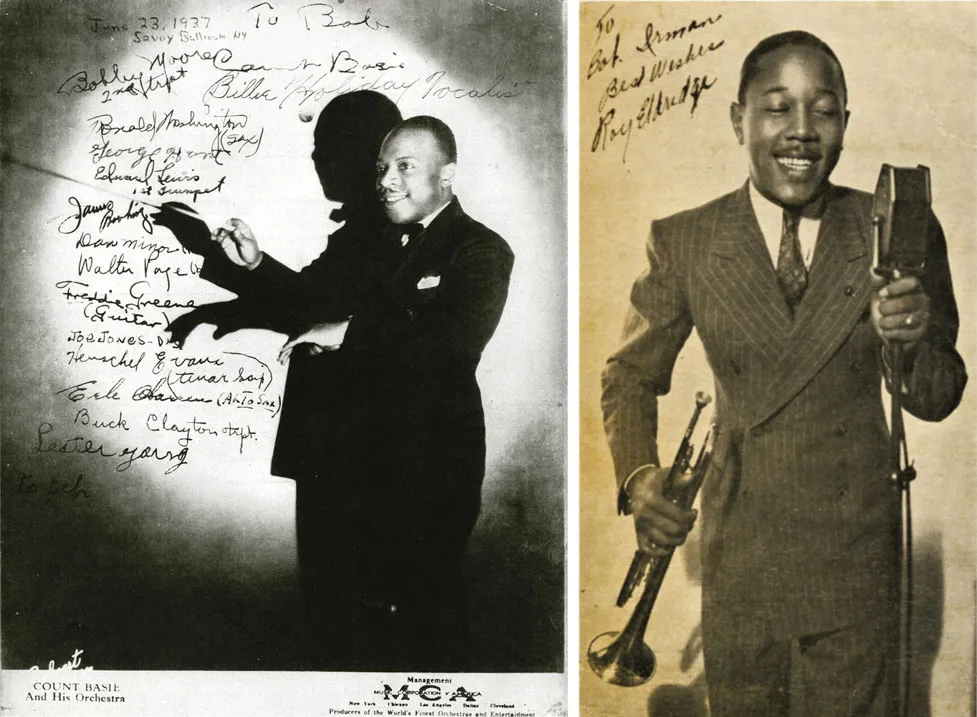

Their photographs show the leading players on the bandstand creating moments of musical history, but the contribution of these images to our understanding of the music goes beyond performance portraiture. Jazz photographs document the wide variety of musical practices embraced by jazz musicians; the development of instruments and playing techniques; and provide insights into musicians’ lifestyles, working conditions, social, communal, and familial activities, and professional practices and associations. The use of photography in publicity material tells us how musicians wished to present themselves and indicates changes in the place of jazz in American entertainment and visual culture. Photographs show the variety of and evolutions in the spaces in which jazz was performed, the nature of audiences and dancers, and provide pointers to the relationships between musicians and spectators. Musicians often inscribed messages on the face of photographs, which tells us about their relationships with mentors and colleagues, professional associates, friends, family, and fans. In short, these photographs reflect the hopes and concerns of a period when the country was undergoing cultural upheaval on a scale never previously experienced and speak of personal, social, and racial struggles and achievements as much as the strivings of men and women toward a new form of artistic expression.

The relationship between photographers and jazz dates back to the earliest days of the music and is uniquely comprehensive. Anthologies such as Al Rose and Edmond Souchon’s New Orleans Jazz, Orrin Keepnews and Bill Grauer’s Pictorial History of Jazz, and Frank Driggs and Harris Lewine’s Black Beauty, White Heat present images of jazz pioneers from the early-1890s: “Cracked and faded with age,” as Rudi Blesh affectionately explained, “they are documentary relics of a bygone era from the tooting of Fate Marable’s calliope on the Mississippi River to the polished notes of Bix Beiderbecke’s green gold cornet.”2

As the number of photographers interested in the field grew in the decades that followed, images of virtually every jazz musicians of any stature were made and many are now available to researchers in private or public archives, published anthologies, and websites. These archives range from the enormous collection assembled by Frank Driggs and now held by Jazz at Lincoln Centre, around 3,500 photographs by Francis Wolff recently made available online from the Mosaic Records website, some 2,500 items in the William Gottlieb collection in the Library of Congress, and around 2,250 photographs of the writer, editor, critic, and producer Dave E. Dexter at the University of Missouri. Smaller collections, such as the 200 images at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music made by the photographer Frank Kuchirchuk in the early-1950s and the jazz photography of James Arkatov, a Russian-born cellist with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra now held by UCLA Library Special Collections, contain important images although they are almost entirely overlooked by jazz scholars. While the photograph of Buddy Bolden reminds us that the authenticity of some of the earliest images in these collections might be problematic,3 the fact remains that the entire history of jazz as an art form has been extensively documented in images of its most important practitioners in publicity portraits, in studio or live performance, in informal jam sessions, traveling between venues, or in social settings.

Jazz photographs stand as both documentary records and artifacts of enormous expressive potency. As documents they are of inestimable value to critics, historians and musicologists, discographers and biographers, enthusiasts and collectors. They provide evidence about the nature and compositions of jazz bands, changes in instruments, and the ways they were combined; they offer clues to the backgrounds of individual musicians, locate itinerant musicians in a particular place at a particular time, and show how their identities as artists developed; recording studio photography has helped identify players on particular records and provides an understanding about how recording techniques developed over time; and we can sense changing social trends and the halting progress toward integration in photographs of musicians at work, leisure, or traveling. The affective potency of jazz photography is however just as important as their evidential status. Jazz critics and enthusiasts alike find that these expressive images often stimulate memories of performances and experiences that often hold deeply personal meanings. In describing their evocative power, these images are frequently described as “atmospheric,” a term used to foreground the ability of photographs to rekindle the experiential impact of live performance and the personal memory of these experiences.

In short, jazz is an art form whose entire existence has been both documented and expressed through photography and it is this combination that situates these photographs among the most valuable visual records in modern American history. That such an archive exists is due to the enthusiasm of photographers to what for significant periods was a minority—and always racially charged—music. Some made a commitment to documenting jazz at particular stages in their careers, including those to whom the label “jazz photographers” is most often applied: Charles Peterson, Herman Leonard, William Claxton, Francis Wolff, Charles Stewart, Dennis Stock, Herb Snitzer—to name but a few. Rarely, or at best insufficiently, remunerated for occasional illustrations for magazine articles, album covers, or publicity shoots; operating under difficult conditions; and usually struggling to find exhibition opportunities at the time, they are now celebrated as key contributors to the jazz photography tradition. These photographers have attracted considerable attention, but they were by no means the only ones with an interest in the subject. Studio portraitists, art photographers, fashion photographers, documentarians, and photojournalists also made photographs of jazz musicians in the course of their professional practices and as personal projects. These photographers were a diverse group including among their ranks African American as well as white studio workers and the émigrés and exiles who arrived in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century.

I. The significance of jazz photographs

First published in Life in 1938, Charles Peterson’s portrayal of a “typical” swing fan collages a variety of media as collectively they facilitated the experience of jazz (Figure 4). The fan sits beside his radio, his left ear close to the speaker; his body is moving with the beat of a swing band, feet jerked off the floor in excitement. A record is turning on the turntable, a record store bag hangs over the back of the chair, and a pile of magazines illustrates the place of the jazz press. Photographs are pinned to the wall. Peterson’s image is a contrived tableau vivant, but his portrayal appears accurately to represent the social and demographic characteristics of a typical swing fan of the period and effectively directs attention toward the role of photography as part of an immersive process through which many aficionados of the period consumed their music.4

Jazz photographs have always been important to fans, enthusiasts, and collectors. By the late-1920s photography was firmly enmeshed in a network of technologies that included recorded music, radio, and illustrated print media. These technologies changed the ways in which the music was consumed and enjoyed, creating “circles of resonance” in which “listeners shared, debated, analyzed, and fought, often passionately, over their personal patterns of empathy and appreciation for what they heard in the grooves of 78 rpm recordings.”5 Young white collectors and enthusiasts like Peterson’s swing fan went to considerable lengths to acquire signed photographs of their jazz idols. Bob Inman’s swing era diary recounts how as a teenager in the mid-1930s he toured New York streets to call on magazines and management offices, visiting musicians in their hotels, dressing rooms, or on stage; or (as in the case of Roy Eldridge) writing directly to the musician’s home address to secure signed photographs (Figures 5a and 5b).6 Letters from the mostly white readers of Down Beat confirm that signed photographs were treasured artifacts among fans. One correspondent complained that Charlie Barnet was not a “solid guy” because he refused to sign a photograph while another praised Gene Krupa as “the finest guy there is” because he spoke to the writer behind the stage and gave him five autographed photographs.7

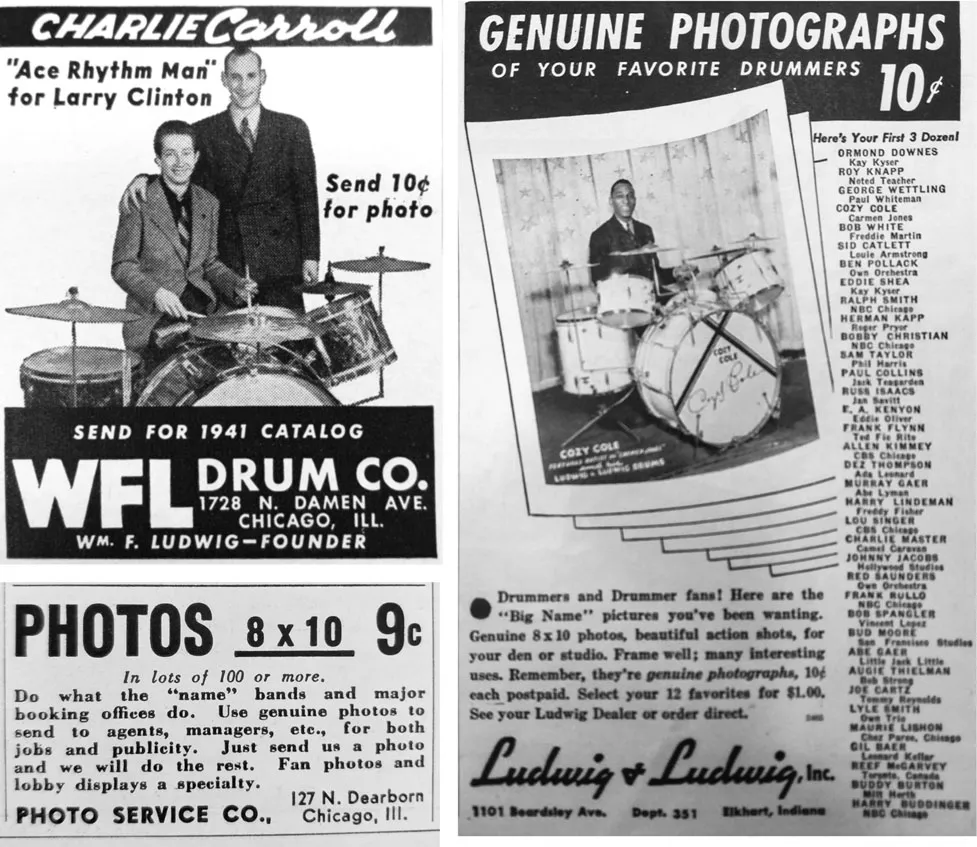

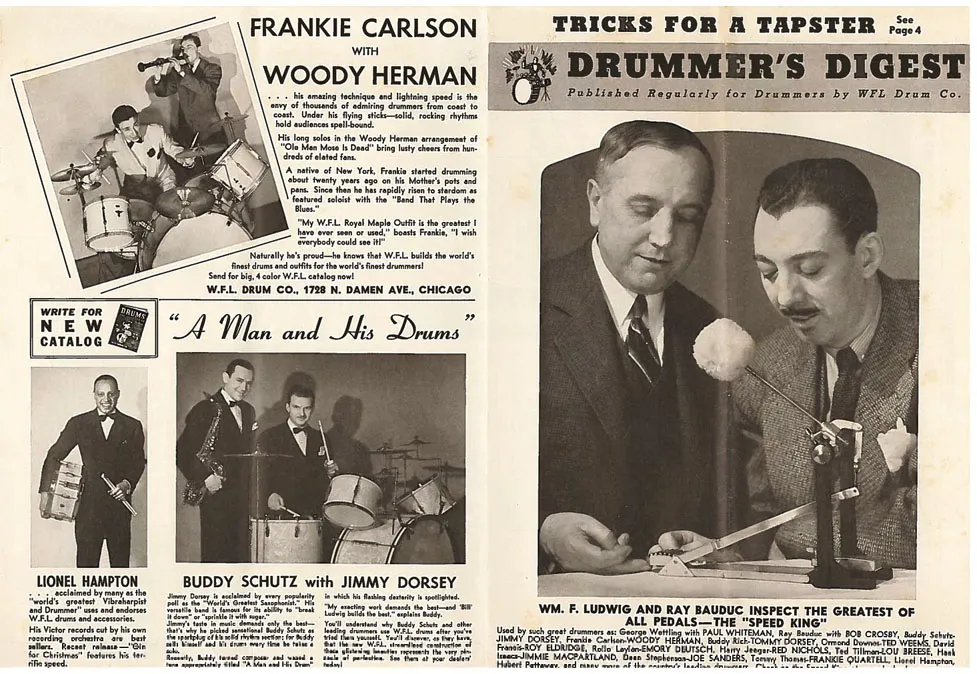

For many years Down Beat and other music magazines carried advertisements offering photographs of jazz musicians “ready for framing” for as little as 10c. each. Around 55 percent of nearly 1,500 testimonial advertisements appearing in Down Beat between 1939 and 1949 included a photography offer as an inducement to enquiry. A total of 175 advertisements in the period (12 percent) offered a free (or nominal charge) 10 × 8-inch photograph of the musician(s) featured in the advertisement (Figures 6a and 6b). Advertisers used photography to extend the reach and life span of the sales dialogue initiated by advertisements with a range of visual material, most commonly photographic brochures or “magazines.” Always copiously illustrated, advertisers positioned these brochures as packed with helpful information drawn from the life and work of the endorsers by combining detailed product information with personality photographs, discussions about bandleaders’ styles and techniques, and tips for success. These brochures elaborated and reinforced the advertisement by drawing on the same visual imagery attracting the enquirer initially (Figure 7).8

In the pretelevision age photographs filled a gap in the demand for visual information for black as much as white enthusiasts. African American families had a long tradi...