![]()

‘Our hope is that we will see a relatively stable government in Afghanistan, one that…provides the foundation for future reconstruction of that country.’

Senator Joe Biden, 2001

‘[The] alternative to nation-building is chaos, a chaos that churns out bloodthirsty warlords, drug traffickers and terrorists.’

Senator Joe Biden, 2003

‘Our mission in Afghanistan was never supposed to have been nation-building.’

President Joe Biden, 16 August 2021

Nearly 3,000 people died in the terrorist attacks on the United States of 11 September 2001. Americans—and television viewers around the world—watched the largest terror attack on American soil unfold live on television as suicide bombers flew the aircraft they had hijacked into the twin towers of the World Trade Center and into the Pentagon. The towers burned and collapsed, taking neighbouring buildings with them with such violence that downtown New York, covered in a grey shroud of ash and paper, resembled the set of an improbable Hollywood thriller. When the shock had subsided, the clamour for a swift and brutal response grew, and US President George W. Bush responded.

On 18 September, President Bush signed into law a joint resolution authorising the use of force against those responsible for attacking the United States on 9/11. The war against Al-Qaeda and its hosts, the Taliban, began on 7 October, when the US military, with British support, began a bombing campaign against Taliban forces, launching Operation Enduring Freedom. The response, engineered by the United States and supported by its key allies, notably the United Kingdom under Prime Minister Tony Blair, was simple. It followed a plan, developed by the Central Intelligence Agency and supported by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, that applied a ‘light footprint’. This was essentially the reinforcement of Northern Alliance guerrillas who had held out against the odds against the Taliban, supported by Western special operations forces (SOF) and air power, in an effort to remove Al-Qaeda—the terrorist organisation run by Osama bin Laden that was responsible for the destruction of the twin towers—by toppling its Taliban hosts.

As President Bush put it at the time, ‘We are not fielding a nation-building military. We are a fighting military. We need to define the mission clearly.’1 Bush and others, including National Security Advisor (and later Secretary of State) Condoleezza Rice, had criticised the outgoing Clinton administration for what was termed ‘international social work’ in trying to make the world a better place through forays such as Bosnia, Haiti and Somalia.2

Despite intending to follow a more restrained foreign policy on coming into office at the start of 2001, after 9/11 the Bush administration faced ‘only unpalatable choices’, as US scholar and commentator Robert Kagan observes. It was trying to prevent a descent into chaos after the fall of the Taliban, while staying out of nation building. ‘In the end,’ notes Kagan, ‘Bush officials decided they had no choice but to stay for a while and try to establish a government that would allow American troops eventually to depart without fear of a return to the pre-9/11 circumstances.’ It involved doing ‘what the US military has always done, or tried to do, when engaged in occupations in Vietnam and in the Balkans in the 20th Century, in Cuba and the Philippines decades before that, and even in the South after the Civil War: building schools and hospitals, trying to reduce corruption and to improve local administration.’3

While the initial aim was to remove Afghanistan as a safe haven for Al-Qaeda terrorists, and that meant going after the Taliban who refused to give them up for cultural and ideological reasons, this quickly changed once complacency about the depth of the problem in Afghanistan had been swept away by facts on the ground. As Rumsfeld put it to Lieutenant General Dan McNeill, the US Army’s senior commander on the ground in the spring of 2002, ‘Do two things—pursue terrorists to capture or kill and build an Afghan National Army.’4 Yet, as McNeill notes, he had no written campaign plan, and the Secretary of Defense had provided no specifics about the size or shape of an army he wanted in Afghanistan.

Rather, the plan evolved organically, through iteration, subject to changes in personalities of ambassadors, commanders and politicians. It was driven also by institutional imperatives, not least the need for NATO to redefine itself in a post-Cold War world. The war in Afghanistan was striking both for the limited influence allies had on the United States (despite some, including NATO leaders, making the case for war in part as a way to maintain such influence) and in its absence of strategic, as opposed to operational, art.

This was not the first time a superpower had become mired in Afghanistan, as Rodric Braithwaite writes in Afgantsy, his history of the Soviet-Afghan War, ‘After a successful operation [the Soviets] would return to their bases and hand responsibility to their Afghan allies. But the government’s military and civilian representatives found it impossible to operate amid a hostile population. … In the end,’ he observes, ‘the Russians had good tactics but no workable strategy. They could win their fights, but they could not convincingly win the war. Their best efforts, military and political, went for nothing. They eventually had no choice but to disentangle themselves as best they could.’5

If anything, in the initial absence of a strategic plan for Afghanistan, the focus of the mission was essentially to maintain the international alliance, ‘of being alongside the United States,’ as one British marine who undertook four tours of Helmand put it,6 ‘at their moment of need to conduct a counter-terrorism operation’. The subsequent state-building process required considerable energy, determination and commitment, not to say political will, in confronting various malign domestic and regional actors. By 2020, total US military expenditure in the Afghan war was over $2 trillion, including future liabilities and veteran costs.7 While the bulk of this money was spent on counter-insurgency operations, $137 billion was earmarked for reconstruction and development. Half of this went to building up Afghan security forces, including the Afghan National Army (ANA), intelligence service (the National Directorate of Security, NDS) and Afghan National Police (ANP).

The cost was huge in other ways, too. By the final withdrawal in August 2021, coalition military fatalities had reached 3,590, of which the US (2,465) and UK (450) had suffered the greatest losses.8 More than 35,000 coalition troops had been wounded or injured in action.9 To this bloody bill must be added more than 4,000 civilian contractor fatalities in what had become America’s and NATO’s longest war.

The price paid by Afghans was staggering. More than 100,000 were killed or wounded in the decade after 2009, when the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan began documenting casualties,10 including up to 70,000 members of the Afghan military and police. By 2016, the Taliban was killing an average of 22 Afghan soldiers and policemen each day with this figure rising threefold during 2018.11 By the time the Ghani government fell in August 2021, it was losing 5,000 soldiers and police per month to casualties and defections. Human costs aside, one-third of Afghanistan’s budget was allocated to military or security expenditure.12

The scale of this sacrifice should, however, not put a patina of justification over the West’s shortcomings throughout its intervention and stability mission in Afghanistan. The conventional narrative is that a combination of anorexic Western forces, weak US revolve (epitomised by the argument that ‘we don’t do nation-building’ and beset by fear of being sucked into another Vietnam), plus the distraction of Iraq, led to disappointment with the Afghan ‘project’.

These difficulties, and eventually failures, were the result of a lack of understanding of the Taliban and of Afghanistan, and of poor planning and limited patience. ‘I felt like we were high-school students who had wandered into a Mafia-owned bar,’ said General Stanley McChrystal on his arrival in Afghanistan in 2002.13 Or as one member of his planning staff put it even more directly, ‘It was stated US policy that they didn’t do nation building in 2002. It was all about bear hunting.’14

Failure was less down to what other people did—or didn’t do.

It was down to the consequences of a weakness in leadership and political direction of epic proportions among the people who were responsible for making the decisions. The blame for this must lie squarely with George W. Bush and Tony Blair, first among equals of those who set the direction for events in Afghanistan and then, crucially, in Iraq.

On discovering that the country was badly broken, that the ‘get rid of Al-Qaeda’ imperative could not be guaranteed in even the short-term without a minimum of internal stability in Afghanistan, and that stability in turn could not be achieved without improving governance, decision-makers soon realised this had to be enabled through a comprehensive approach combining security with governance and economic development.

Thus, the initial kinetic counter-terrorism mission morphed into state-building and counter-narcotics, which found NATO forces in far-flung places like Helmand with no clear purpose and without the tools to defend themselves, let alone build a different state. To make matters worse, as the memory of 9/11 faded, the Taliban’s traditional patron, Pakistan, reverted to playing both sides—the West and the Taliban—against each other, for reasons both of its own geopolitical and domestic insecurities and elite interests.

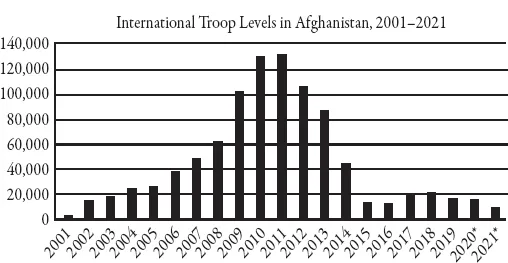

Figure 1

Data from 2001–2019 is from the Afghanistan Index, Brookings Institute, 2020. The above data is in terms of annual averages of US and international troop levels. 2020 and 2021 figures show troop numbers of the Resolute Support Mission, which includes troops of NATO allies and partners as of February 2020 and 2021 respectively.

During a briefing with reporters in Kabul on 1 May 2003, Rumsfeld declared an end to ‘major combat’ in Afghanistan, the announcement coinciding with President George W. Bush’s ‘mission accomplished’ declaration of an end to fighting in Iraq.15 At the time there were fewer than 20,000 international troops in Afghanistan. By 2011, there were over 130,000.

As violence ratcheted up, a vicious cycle kept the West engaged and simultaneously caused resentment and violence to rise. This prompted a surge in coalition troops from 2010 to enable a withdrawal of combat forces, followed by a further drawdown of advisers to the point that, by 2015, almost all the fighting was being done by the Afghans themselves. The military withdrawal was delinked from the security environment, yet it is best to try to negotiate a political deal from a position of military strength, not one of weakness. This is at best an ahistorical, at worst a careless interpretation of the politics and methods of peace-making, and of American policy in particular. It reflects a failure, from the outset, to think things through to the finish.

The absence of a strategy, and the failure to develop a cogent linkage between military outcomes and a political solution internally and regionally, are key lessons from other conflicts, notably the US experience in Vietnam. While the Vietnam parallel is resisted by many in the Afghan government, for reasons highlighted below, it reminds us of the primacy of politics in war, a lesson that should be noted by outsiders to any conflict.

Any visitor to Afghanistan during the war, and anyone (including both of us) who served as a military or civilian adviser in the field during the conflict, could not fail to be struck by the extraordinary commitment and competence of military commanders. Indeed, military forces were put into situations where they should never have been. This included regularly having, at least in the early days of the intervention, to use military tools and diplomatic initiatives to create political compromises among feuding parties to bring them into the government tent, or at least prevent them acting openly as spoilers.

But this hard country was never going to be changed by a string of bright young Brigade and Battalion Commanders doing their best (‘We’re making progress, but challenges remain’…) in Helmand, Kandahar, Zabul, Kunduz, Nangarhar, Uruzgan and dozens of other barren and hostile spots. The war was not inherently unwinnable, perhaps, but the missions these mostly very capable, brave and selfless men and women were sent on, within the resource and timeframe parameters they were given, were often unachievable. Like the highway to hell, the road to defeat in Afghanistan was paved with good intentions.

In Afghanistan, for all the organograms and rhetorical posturing, there was no integrated plan linking the military defeat of the insurgency with development and improved governance, and no cogent theory of victory explaining how this would ensure sufficiently enduring stability to allow the military to leave.

This was most notable in the confusion among strategic goals, which added to a general unwieldiness of operations. Rather than bringing order from chaos, on which success depended, this confusion often led to the reverse. While counterinsurgency theory holds that military tools are secondary and subordinate to civilian political, governance and development means, the subordination of capable military forces to civilian agencies was unachievable in practice in Afghanistan. This was due to a lack of civilian expertise, reluctance of aid organisations to integrate efforts with the military, endlessly rapid rotations, and civilian risk-aversion exacerbated by the underwhelming quality of some, though by no means all, the agencies involved.

There were strenuous—and, often, successful—attempts to improve the tactical performance of armies that were not, for the most part, designed, trained or equipped for the task they faced in Afghanistan. For all the puffing up of the relevance of Britain’s experience in Northern Ireland, the intervening coalition in Afghanistan mostly comprised militaries focused on conventional warfare.

As fast as the painful lesso...