eBook - ePub

Sonic Wilderness: Wild Vinyl Records

Mark Harris

This is a test

Share book

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sonic Wilderness: Wild Vinyl Records

Mark Harris

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Sonic Wilderness accesses the critical value of unusual vinyl records that concern our relationship with nature. These wild records reveal unconventional perspectives on the entanglements of human life with animals, gardens and plants. They form a lyrical unconscious exposing the conventions and ideologies of popular music, their warped perspectives and acoustic radioactivity comprising a resistance to enduring social, psychological and political conditions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Sonic Wilderness: Wild Vinyl Records an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Sonic Wilderness: Wild Vinyl Records by Mark Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Arquitectura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Riot Parks, Psychogardens and Black Yards: Sites of Labour and Alienation

Parks and gardens are spaces of physical and psychic turbulence. Songs tell of bad things that feel more incongruous for happening in pleasant green environments. Parks have frequently hosted mass protests leading to police repression. They have sheltered individual attackers who melt away into the undergrowth. Suburban garden flowers and shrubbery conspire to orchestrate a private hell of mental disintegration. It was the nineteenth-century illustrator J.J. Grandville who saw how middle-class park promenades, that conspicuously paraded new-found wealth and leisure amongst the flowers, could be depicted as a descent into horticultural in-breeding and atrophy.

In 1969 an epochal park furore pitched the Berkeley counterculture against ultra-violent Alameda County Sheriff’s deputies, fuelled by Governor Ronald Reagan’s animus against hippies and students. Two decades later a similar volatility that enveloped New York’s Tompkins Square was addressed in songs by white musicians who were nevertheless blind to the experience of temporary residents of the park whose evictions had provoked those 1988 riots.

The underside to these exhilarating mass participatory acts are songs of the lone visitor dealing with threats in under-policed and secluded parks where lyrics concern casual violence in tranquil settings. This sense of precarity extends to private spaces, to those suburban psychogardens where mental health disintegrates in the deceptively benign setting of flower beds and trimmed hedges. Although farming has seemed an alternative to that suburban dead end, particularly with 60s communes, the reality of tedious farm labour has inspired songs about unproductive hedonism and dull cultural life.

All too often the urban park and vacant lot become refuges for a disproportionate number of homeless people who are then vulnerable to racial violence and forced evictions. Parks and public gardens have always been racialised, prohibiting access to people of colour or imposing horticultural collections pirated from elsewhere in the empire. If anything, the classification of ‘public park’ masked the profit-driven botanical research that colonial botanical gardens served. Their intrinsic beauty in landscaping and plantings furnished the perfect cover for political and economic objectives. It should not be surprising that people of African descent have found little in organized nature to sing and write about. In consequence, songs of the private Caribbean garden by Junior Murvin and Barrington Levy allegorise the cultivation of Rastafari social harmony and support for black solidarity.

Black songs and poems concerning gardens turn to the private yard, ancestry and the nurturing of plants as analogies for community survival against the odds. Such songs affirm the historical value of the provision ground and herb garden for the formerly enslaved, required to grow their own food for survival on plantations. African American gardens in the southern United States show how smallholding enterprises endured with the pride taken in cultivating all the produce needed for prosperous family life. The Black Seeds’ and Archie Shepp’s songs directly address this community touchstone while Lead Belly and Gwendolyn Brooks allude to the sanctuary of the private yard as it facilitates erotic adventure.

I met an anarchist in Tompkins Square Park

Parks are contested spaces whether fenced in for use by the residents of houses surrounding them, occupied by drug users like Berlin’s Görlitzer Park, or by teenagers and lovers seeking community and privacy away from parental surveillance. They have also been lawless nocturnal havens where muggers, rapists and flashers may operate with impunity. Predators are shielded by the same features that afford seclusion and arboreal variety to park visitors. The received idea of safe urban spaces was grist for filmmakers like Michelangelo Antonioni whose 1966 Blow Up centred on a killing in a London park, unwittingly documented by a fashion photographer. The plot of The Conversation, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 thriller, developed from a San Francisco park surveillance recording of a murder being planned. Park use is unofficially for families by day and more adventurous types after dark. Louis Aragon writes in Paris Peasant of a night-time stroll in the 1920s with friends through Parc Buttes-Chaumont, attending to the shadows and sounds of lovers on benches.

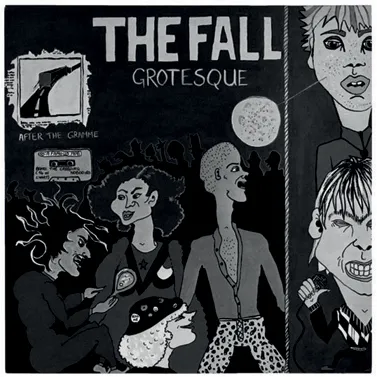

As if from the side of the Buttes-Chaumont lovers, The Fall’s 1980 ‘In The Park’ tells of plein-air sexual mishaps in the bruising staccato of their early uncooperative brand of punk. Singer Mark E. Smith’s merciless and humorous lifelong examination of human vanities takes on a rare self-deprecating humility to admit flawed outdoor sexual adventures: ‘I take you to the park up the road / But here is the rain / Rain makes policemen no threat / … / And we will have sex here / Here, here / Couch, shagged out / There’s no hard-ons / It’s just come and it’s gone.’ Fifteen years on, the groove and romantic outcome are the opposite for Stereo Total’s ‘Dans Le Parc’ about passionate outdoor clinching without heed of passers-by: ‘Allongé dans l’herbe / D’un parc de la ville / On oublie les passants / … / On est de la même taille / Ta bouche sur ma bouche / Tes pieds sur mes pieds / Nos deux sexes se touchent.’ Despite punk beginnings, Stereo Total’s singer Françoise Cactus was an accomplished shape-shifter of music idioms, compounding homage with parody. Her adoption here of the languorous voice of a classic chanteuse restores to the lead guitar and snare drum accompaniment much of the rebel sexuality at the core of rock and roll.

Fig. 43: The Fall, Grotesque, 1980.

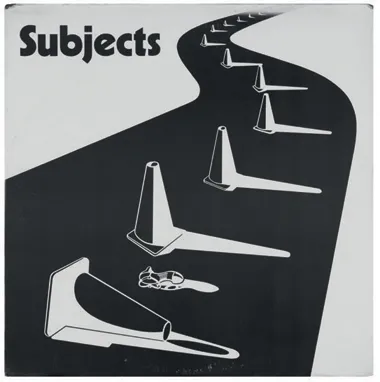

Where the likelihood of dangerous encounters is their focus, the lyrics and accompaniment of songs about parks conjure up zones suffused with menace. The entire park assumes an atmosphere of violence. Post-punk California band Subjects released just one record, a 1982 lyrically playful 12” EP overflowing with musical ideas that included ‘Leather In The Park’ about the anxieties of venturing into such spaces. By blurring the properties of plant and predator, Subjects create an image where the total environment conspires to ambush the visitor: ‘Creepers (watch your step) / Crying in the cracks waiting for you. / Creepers (over the grass) / Wear good shoes and be ready to move / over the grass in the park. / And don’t smile, and don’t talk. / when you walk through the park.’ Opening with a memorable guitar riff, continuously repeated to generate an unsettling urgency, the cleverly constructed and fast-paced song has vocalists Brenda Briggs and Dominic Willison exchanging lines with a briskness that conveys a sense of panic.

Fig. 44: Subjects, Leather In The Park, 1982.

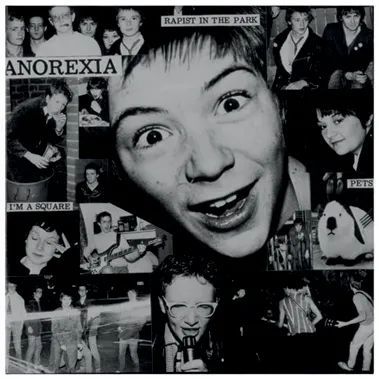

Even if their music verges on punk impishness, the lyrics of Watford band Anorexia’s 1980 ‘Rapist In The Park’ are explicit in naming this fundamental threat to which Subjects only allude. Appropriately it’s female singer Kim Glenister who accurately expresses this profound anxiety of women: ‘Rapists lurk in the dark / wo oh o o o / Footsteps behind you in the park / wo oh o o o / They’ll muffle your helpless cries / wo oh o o o / And haunt you with their evil eyes/ wo oh o o o / Time will not heal the scars / wo oh o o o / Because when you’re raped / Your life is marred.’

Fig. 45: Anorexia, Rapist In The Park, 1980.

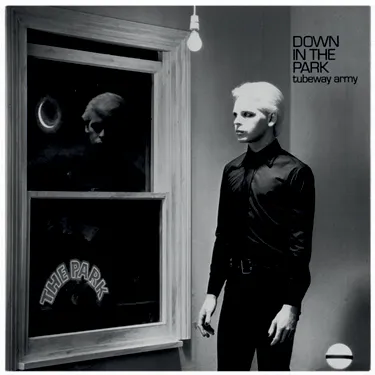

In Tubeway Army’s ‘Down In The Park’, the most effectively sinister park song of the punk era, singer Gary Numan all too casually references this violation: ‘You can watch the humans / Trying to run / Oh look there’s a rape machine.’ The record starts by repeating four low synthesizer notes to introduce the malice within the song’s lyrics: ‘Down in the park / Where the mach-men meet the machines / And play “kill-by-numbers” … Where the chant is “death, death, death” / Until the sun cries morning.’ Phil Oakley’s comment that Numan’s music was ‘exploring the problems of alienation’ explains the turn to a more mechanized sound and rhythm by these early electronic singles that focused on the estrangement of many economically and politically marginalized young people at the time (Reynolds, 2009: 294).

That the parks of Numan’s and Smith’s music were being repurposed by disaffected citizens into their own social spaces reveals how little was ever on offer in their home localities to help develop skills or deal with addiction and boredom. The music and lyrics of these songs turn to the microcosm of park environments to reveal how new forms of social life are remodelling modern cities. Numan’s narrative of ambiguously gendered and schizophrenic machine-human identities depicts a space inhabited by damaged individuals out of necessity and fascination, and one where they will inevitably encounter more abuse: ‘Down in the park with a friend called five / I was in a car crash / Or was it the war / But I’ve never been quite the same.’

Fig. 46: Tubeway Army, Down In The Park, 1979.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea gives a comparable example of this sense of loathing in main character Roquentin’s park experience of overwhelming nihilism and bodily dissolution. Roquentin has moved to a dreary regional town to write a historical biography in the local library. He suffers debilitating psychological attacks where his surroundings force their base materiality onto his senses so that a separation from objects can’t be maintained: ‘Things have broken free from their names. They are there, grotesque, stubborn, gigantic’ (Sartre, 1975: 180). Fittingly, his nadir occurs in the dullest of locations, the municipal park. Such park developments surged in nineteenth-century France, led by initiatives taken in Paris by Emperor Napoleon III and city planner Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. The motive for municipal parks was to improve working class morality by letting air and sunlight flood into the slum areas, as Napoleon put it, ‘just as the light of truth illuminates our hearts’ (Harvey, 2003: 107).

As ever, users of public spaces bring unintended needs, ideas and tactics (Michel de Certeau’s term for creatively opportunistic appropriation), to repurpose these localities. Napoleon’s urban planning ideals are challenged by songs that reterritorialize violence from slums to parks as much as by Sartre’s idea of municipal gardening provoking psychic implosion. On Roquentin’s last visit, a tree root presses down with an incomprehensible and unnerving accumulation of matter. His conviction of having encountered the fundamental nature of being, as oscillating between the filthy and marvellous, takes place in the most managed and mediocre environment that conceals its terrifying amorphousness beneath a mimicry of bourgeois pleasantries: ‘When I got to the gate, I turned round. Then the park smiled at me. I leaned against the gate and I looked at the park for a long time. The smile of the trees, of the clump of laurel bushes, meant something; that was the real secret of existence’ (Sartre, 1975: 193). The illuminating truth encountered in the municipal park is dark: ‘was it more than black or almost black? … It resembled a colour but also … a bruise or again a secretion, a yolk’ (Sartre, 1975: 186-7).

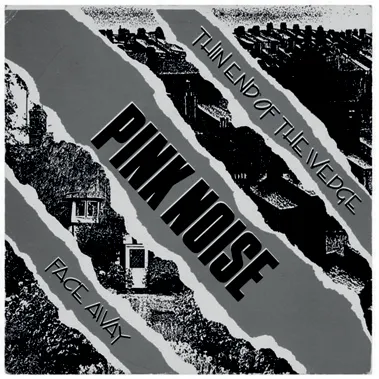

Fig. 47: Pink Noise, Thin Edge Of The Wedge, 1987.

From the earliest inauguration of parks, economic, mental, physical and cultural benefits have been claimed as returns for investment in public space. The question is to whom these are beneficial. Pink Noise’s 1987 postpunk anthem ‘Thin Edge Of The Wedge’ casts parks as exclusive sites of privilege: ‘There are country parks and country homes, / On the south side of my town, / But to the north and west, / Where they won’t invest, / All the homes are falling down’. The Infrared Helicopters’ 1979 ‘South Hill Park’ delivers a blunt generational cultural critique that qualifies the dismissiveness of the song’s rudimentary musicality and deskilled singing. Bracknell Arts Centre, the main attraction in this twenty-four acre park, was at the time a venue for mainstream jazz and community cultural events. The song’s irony lies in its gleeful inadequacy in relation to that culture: ‘South Hill Park, a boring old park / A place where all the hippies go / We give meaning to your lives / They’re ignorant, don’t care, don’t know / No, no, no, you can’t ignore us / We’re a new culture, a part of living society / Long live rock, South Hill Park is dead … A place where all your money goes.’

Fig. 48: The Infrared Helicopters, South Hill Park, 1979.

Historical patterns of exclusion continue to affect the willingness of African Americans to use parks recreationally. Management of public spaces falters in communicating what might be of value there for people of colour who know they have been unwelcome for centuries. As facilities expanded in the early twentieth century, administrators of integrated urban parks could not ensure that ethnic groups wouldn’t involuntarily segregate into racialised zones, nor could they prevent pitched battles over boundaries. In any case, by the 1950s the number of state parks available to people of colour was unlikely to have exceeded five percent of the total (Cranz, 1982: 200). In some parts of the country exclusion was complete, for at that time there was no evidence of any parks in Louisiana, Mississippi, or Texas that African Americans could legally use, whereas more than sixty existed for whites (R. McKay, 1954: 703). This appropriation and protection of land for white recreational use was standard practice. KangJae ‘Jerry’ Lee writes about the active exclusion of people of colour where the process of constructing New York’s Central Park caused the obliteration of the black home-owning community of Seneca Village (Lee, 2020). Examining Charles Rosenberg’s 1872 engraving ‘The Terrace, Central Park’, Galen Cranz shows how the park was inclusive, provided economic hierarchies and racial roles were respected: ‘a bum, a black nanny with a white child, a family group of three adults and three children’ (Cranz, 1982: 208). As a young man Nile Rodgers was a member of the Black Panthers. ‘At Last I Am Free’, written for Chic, referred to Rodgers’ narrow escape from a police beating after attending a Panther rally in Central Park (Lester, 2011). No surprise then that rap songs like Ghostface Killah’s ‘In Tha Park’ have acknowledged the role of park space in the origins of the music: ‘Hip hop was set out in the park / We used to do it out in the dark.’ Redressing this legacy of racial exclusion, KRS-One in ‘Outta Here’ stresses the subversive act of taking back space for performance and pleasure: ‘So we would go to the park when they was jammin’ to hear rap / I used to listen till the cops broke it up’ (Adler, 2013).

Public botanical gardens established by European colonial powers masked other forms of theft and racism. By naming specimens after botanists, Carl Linnaeus’s nomenclature disqualified indigenous names and those of most women botanists, separated plants from their ‘barbarous’ localities, and reordered them according to European botanical history, in what Kincaid calls the ‘murder’ and ‘erasing’ of colonial acts of pirate horticulture (Kincaid, 1999: 122). The 1,600 botanical gardens founded by the start of the nineteenth century in European overseas em...