![]()

Part 1: The Inheritance

Chapter One

Railway Buildings Today

An Aged and Architecturally Rich Operational Estate

When looking at current or former railway buildings, the observer is presented with a complex living history of the genesis and development of the railway system, which embraces the architectural fashions, whims and peccadillos of all those responsible for the production of its buildings in each period of railway history. This history is sometimes eventful, turbulent and often controversial and it provides a rich tapestry of artefacts, most of which, unlike many more recent bland structures, can be dated and attributed to specific architects, engineers and contractors or privately commissioned consultants.

Although a modern transportation network relies on up-to-date engineering and operational technology, the railway buildings in the UK comprise an eclectic mix of structures representing nearly two centuries of engineering and architectural prowess, progress and pioneering development. This lengthy timeline does have its consequences today though and it is against the sometimes conflicting mix of modern operations and historic infrastructure that the buildings should be viewed, as this presents not insubstantial challenges in respect of costs and operational practicalities.

Most station buildings reflect periods of change, development and civic context. Here at Reading the new platform access deck, designed by Grimshaw and opened in 2012, is located adjacent to the second station built on this site in 1868, which replaced Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s 1840 station. (Photo: Jon Cunningham)

The buildings and underlying infrastructure that support the current train services and passenger activities are, in the main, the legacy of the nineteenth century. However, unlike the core engineering structures such as bridges, viaducts and tunnels, the basic elements of which are often still capable of fulfilling modern needs without deleterious impact on their appearance, these buildings have often been significantly altered, adapted, replaced or removed as the nature and scale of railway operations has progressed through its historic phases. This same need for change and development continues today.

The operational railways ‘estate’ as it now stands is unique in its engineering make-up and building stock. Although other large property and landowners perhaps have more historic portfolios with buildings ranging over a wider period of history, the railway estate is the only one with physical continuity and connectivity across the entire country. This unique attribute contributes significantly to its architectural character. In addition to the operational buildings, there are also many former railway buildings across the country that have found themselves unwanted due to system cutbacks or unusable because their functionality is no longer relevant to contemporary operations. Together these combine to represent every manner of architectural development, both evolutionary and revolutionary. Many buildings, such as stations, embraced the architectural influences and manners extant at the time of building, but many represent and reflect entirely new building requirements such as signal boxes, carriage and wagon works, and locomotive roundhouses.

Architectural Styles and Diversity

The operational infrastructure of today is a complex mix of structures and buildings of all types mainly dating from the early nineteenth century onwards although there are also earlier buildings in the portfolio where, for instance, they were inherited by railway companies from the canal companies they acquired in the course of their business.

For many, the words ‘railway architecture’ conjure up images of grand Victorian or Edwardian terminals or country stations resplendent with wrought-iron filigree. Indeed, stations are probably the most familiar of railway buildings, but there has often been an equal, or greater, number of other operational buildings to accommodate supporting operations. These may include administrative offices, signal boxes, motive power and maintenance depots, warehouses, hotels, lineside buildings, water towers, sub-stations, control rooms, dockside buildings and so on. In the second half of the twentieth century, the range of building types expanded to embrace such facilities as computer systems operations centres, research establishments and even a hoverport terminal.

The railway buildings making up the ‘operational’ estate today represent only a small percentage of the total number of buildings created for railway purposes over the period of its history. Many buildings have come out of operational use as a result of cutbacks to the system or technological development, thus the demise of steam engine roundhouses and the reduction in the number of signal boxes. Fortunately, however, good representative examples of these still exist as other uses have been found for them. They were not all necessarily of great architectural quality, but many were robust and of historic interest. The multi-level stable at Paddington is a typical example; in use now as laboratory accommodation for the adjacent hospital, it once housed and cared for nearly 400 horses in service to the Great Western Railway (GWR) until as late as the 1940s.

The scale of the operational portfolio continues to ebb and flow but whilst the number of buildings has diminished over the last hundred years there are now new buildings being added to suit modern management methods. It is perhaps regrettable that, as well as those already mentioned, other operationally specific buildings such as depot control towers, water towers, transhipment sheds and motor vehicle workshops and so on, that were designed to serve the inner workings of the railway no longer exist to illustrate a bigger picture of the railway architectural story. Whilst it is possible to lament the passing of many wonderful station buildings, one should not perhaps forget the development of these more esoteric buildings, the purpose for which no longer exists.

Robert Stephenson’s tubular iron bridge over the River Conwy is in a particularly sensitive setting adjacent to both the castle and Thomas Telford’s suspension bridge. The bridge abutments were designed in conjunction with Francis Thompson to integrate with the medieval walls alongside which the tracks run. (Photo: Robert Thornton)

It should also be noted that, whilst specifically designed for the railway system, railway operations also impact on, and are associated with many historic sites of greater age, such as the periphery of Conwy Castle and aspects of Hadrian’s Wall in Newcastle. Not only this but the estate comprises many monuments, sculptures and artworks too. The lines and associated infrastructure are also often situated in areas of outstanding natural beauty or conservation areas and take on a different meaning in this context.

Victorian architectural and engineering detailing tends to dominate the historic building stock of the railways and traditional or revivalist building techniques were generally adopted for buildings during the first half of the twentieth century. However, a number of architectural fashions have been adopted since, ranging from International modernism, ‘hi-tech’, brutalism and postmodern to rationalised traditional, ‘eco’ and today’s, yet to be identified, eclectic and esoteric mix.

The bulk of the infrastructure was set down in the nineteenth century with the consequence that the opportunity to create entirely new buildings at any subsequent period did not present itself very often if at all. New elements, such as station canopies or parts of station buildings have been constructed within existing sites, but to some these do not necessarily sit comfortably with their hosts; they do, however, add a further storyline to the history of the premises.

Despite the impact of developing technology and digitization on all aspects of operations, and notwithstanding the major changes already occurring in the signalling world, the range of buildings required to support railway operations is not likely to change significantly in the near future. However, the growth in the passenger business, leading to the need for new stations or the expansion of existing ones is a key driving force in the early part of the twenty-first century.

Scale of Operations and Architecture

Over the first century of railway operations, the amount of land acquired, and the number of buildings created, rendered the railway industry ‘estate’ one of the biggest in the UK. Later aerial photographs of the great works at Swindon, Doncaster, Crewe, York and Glasgow amply demonstrate this. Whilst the amount of land in railway use has been much reduced from its maximum extent prior to World War I, this still makes it one of the largest estates in the UK alongside the National Trust, the Crown, the Ministry of Defence, Highways England, the Forestry Commission and the Church Commissioners.

Few people would be familiar with the range of buildings and the scale of the land needed to support rail operations, much of which would be hidden from view by high walls with carefully controlled access points. Whilst these sites generally contained utilitarian buildings, they often, nonetheless, embraced buildings of architectural and now industrial archaeological interest.

A feel for the scale of these operations can now be experienced following the opening up of former railway sites and yards, such as those at Swindon and now particularly at King’s Cross where the 135 acres (55 hectares) of former railway land north of St Pancras and King’s Cross stations has gradually been converted into contemporary uses whilst simultaneously exposing and exhibiting the very best of the historic architectural qualities this site has to offer. Many buildings within the works footprint at Swindon have been demolished but a number of key buildings remain, notably the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s building by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Some of the remaining workshops have been converted into a retail outlet and offices where the historic structures add significant character to the user experience.

A glance at the statistics related to route mileage and the number of stations spread across the land at three critical periods in their development may help to explain the requirements for buildings and the demands placed on them. At the peak extent of the railway network in the early years of the twentieth century the route mileage of track reached nearly 20,000mi (32,187km) and by the time of the Beeching report – The Reshaping of British Railways – released in 1962, this figure had been reduced to 17,830mi (28,695km). As a consequence of adopting the recommendations of the report, this mileage further reduced to approximately 10,000mi (16,000km) where it remains to this day. Over the same benchmark periods the number of stations dropped from approximately 9,000 in 1914 to 7,000 in 1962. The number of passenger stations closed after the Beeching report numbered 2,363 although 435 of these were already under consideration of closure or, indeed, already closed beforehand. The operational stations on the network now number more than 2,500. The discrepancy in the figures related to station closures is explained by the fact that the word ‘station’ was also applied to freight and goods-only premises in historic records.

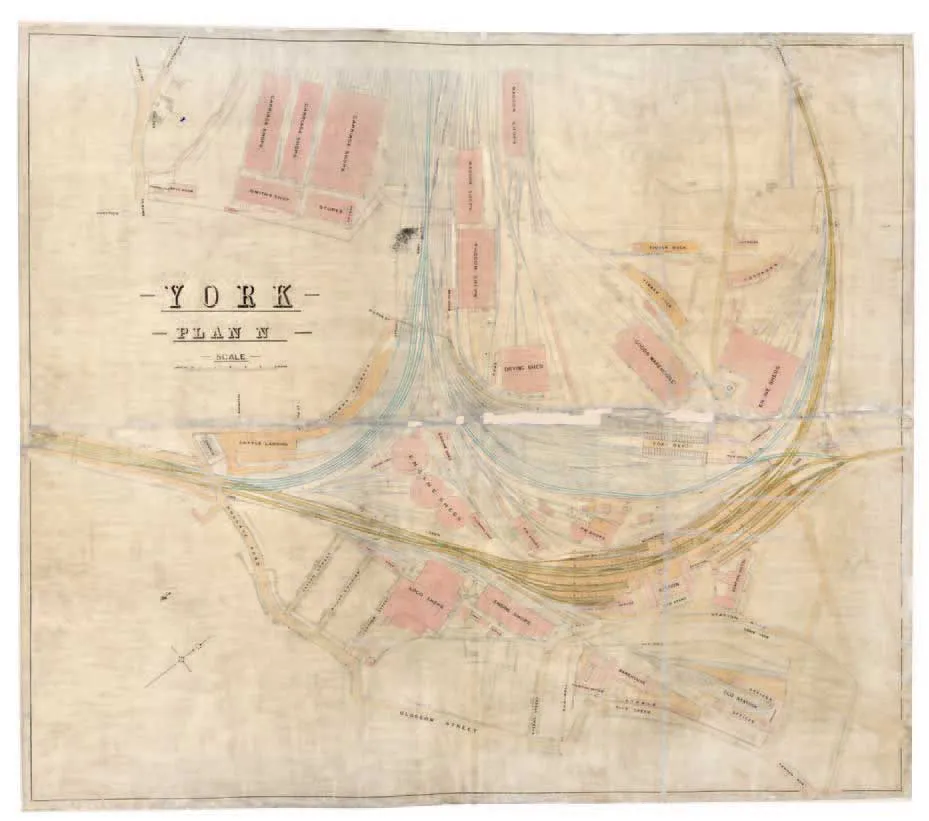

The plan of the railway works in York in the pioneer years of railway development illustrates the scale and extent of the enterprise, which was repeated at a number of centres – usually midway along key routes. Each site had major implications for employment and the demands for specialized buildings.

Until the general adoption of ‘train-load’ freight rather than ‘wagon-load’ freight, stations were very much multi-purpose and often embraced goods sheds, coal depots, animal pens – sometimes including nearby abattoirs – and sundry other offices concerned with the upkeep and maintenance of the railway infrastructure and its rolling stock in the vicinity of the station.

Whilst the closure of a large number of stations may appear alarming it should be pointed out that they were not all of significant architectural quality: many were halts with short platforms and rudimentary forms of shelter, although it is known, of course, that there were a number of important casualties. Whether those with recognized architectural qualities would have survived, had they been preserved for consideration in our current era where ‘heritage’ is more highly valued by the industry and the communities it serves, is a moot point.

In relationship to the scale of the enterprise, it is also interesting to note that manpower requirements have changed significantly in the industry and these have a major implication for buildings of all types whether they be administrative offices, manufactories, carriage and wagon works, signal boxes or the many other specific activities related to rail operations. Up to the time of the nationalization there were approximately 650,000 staff in the employ of railway companies, and this had reduced to just under 475,000 by 1962 to be further reduced in stages to under 150,000 just prior to the privatization of 1994.

The railway ‘estate’ has seen growth and contraction over its period of operation in both usage and the physical infrastructure required to meet demand, but these two aspects have not always been analogous. After unpredicted growth in passenger travel following privatization, the passenger figures approximate to a doubling of demand over the twenty years since the new millennium and, at the tim...