‘It’s not as if an instinct which lies in the race of men from way before Sassetta and Giotto has run its course. It won’t. Don’t listen to the fools who say that pictures of people can be of no consequence …’

R.B. Kitaj

What Is Portraiture?

Our ideas about portraiture are probably rooted in a period that begins in the late middle ages and continues until the end of the seventeenth century. This period saw the revival of the individualized, au vif, portrayal of the powerful, influential and successful. The seventeenth century was the era of Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens and Diego Velázquez, and of the most exquisite painting from life. By the nineteenth century, the portrait is very often, although of course not always, a solid signal of status. Like much Victoriana, such paintings are usually highly crafted, over-engineered even. They can be so well-finished that sometimes one feels the paint has been polished up to produce pure alabaster and the sitter, in consequence, is petrified. In the twentieth century, Modernism set off in pursuit of the interior. Inner truths were sought, unlikely and unfamiliar faces, gathered in from Africa or found in doodles, acquired resonance. ‘Unlikeness’ became valued and portraiture, which really exists only to represent likeness, waned as a result.

That we should still be making and cherishing painted portraits, then, is something of a conundrum. The annual BP Portrait Award exhibition, hosted by the National Portrait Gallery in London, is one of the highlights of the popular cultural year. The annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters at the Mall Galleries, also in London, draws thousands of visitors. These shows may not attract quite the same glare of media attention as the Turner Prize, but my impression is that the actual footfall is probably greater. Portrait painting doesn’t just survive; it thrives. It persists through all the stuttering complexity of change, through the spurts of action and reaction, imitation and contradiction, through all the layering of new and newer technologies. Through turmoil and fashion, people keep making, and sitting for, painted portraits.

In Europe, recognizably individual portraits date back to the early fifteenth century (although they were possibly not described as portraits until the sixteenth century). Robert Campin’s Portrait of a Fat Man (Robert de Masmines), 1425–30, is an example of the closely observed likeness that still characterizes much contemporary portraiture. There is no attempt to idealize; Robert de Masmines has a fleshy, unbecoming gaze.

The early fifteenth century seems to have been an historical period during which an intensity of looking and recording became necessary or desirable. Prior to this, only Roman portrait busts aspire to the same degree of reality. There are times, perhaps, when our individuality, our uniqueness, has to be set or recorded. It is unlikely, however, that the function of a painted portrait in fifteenth-century Flanders would be the same as the function of a painted likeness today. Beliefs, values, technologies, our understanding of what it is to be human, have all changed since 1430.

It is conceivable that a painted representation in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was used in the way a photograph might be used today, as a communication of appearance. In 1538 an English ambassador in Brussels arranged for Hans Holbein the Younger to paint Christina of Denmark. Henry VIII wanted to see the Duchess’s likeness because he was thinking of marriage. She eventually married elsewhere, but Henry was much taken, it seems, with the sixteen-year-old depicted in Holbein’s painting. Indeed, her likeness still captivates; the painting now hangs in the National Gallery in London. Nowadays, we have more immediate, technological means of communicating appearance, although similar transactions are probably just as risk-laden.

In 1956, the then leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, attacked the ‘cult of the individual’ and specifically the cult of Stalin. Khrushchev argued that this cult ‘brought about rude violation of Party democracy, sterile administration, deviations of all sorts, cover-ups of shortcomings, and vanishings of reality’. More recently, the cult of the individual has had other, more venal, manifestations and cult status has become rather more easy to acquire. I have certainly heard a thirteen-year-old refer to an acquaintance as a ‘legend’. The prospect of becoming famous has elbowed its way up in the collective psyche from being a consequence of achievement to being a career aspiration in itself, fuelled by ‘reality television’. ‘Celebrity’ even has its own professional hierarchy – ‘C listers’ and ‘B listers’, all hoping one day to be ‘A listers’. Fame has been democratized, as was foretold by the shaman, Andy Warhol. It has to be self-evident that we have all scratched away at reality a little by becoming complicit in this cult of the individual. The Co-operative Funeral Service recently conducted a survey of music played at funerals. Frank Sinatra’s rendering of ‘My Way’ was the song most frequently requested to mark a person’s passing. This might be trivializing the point, but portraiture must owe something to our continuing, our rampant, fascination with the individual; with ourselves as celebrities.

Nevertheless, since the Renaissance the portrait has undoubtedly become something of a mark of status, a fitting tribute to a remarkable individual. The great and the good, the celebrated and the infamous, have all gone under the brush. Ironically, the very great are rarely the subject of very great portraits. The subjects of those truly unforgettable paintings, such as the portrait of Baldassare Castiglione by Raphael, are often rather minor historical figures. Even those who were kings, like Philip IV of Spain, are arguably more easily remembered today because they were painted by such painters as Velázquez. Another example, Madame Moitessier, may well have done it her way, but we think of her now because her husband, a wealthy banker, had the means and judgment to commission Ingres to paint her portrait. When we call to mind the painting of Lord Ribblesdale, we remember John Singer Sargent, just as in the crematorium it is difficult not to think of Frank Sinatra.

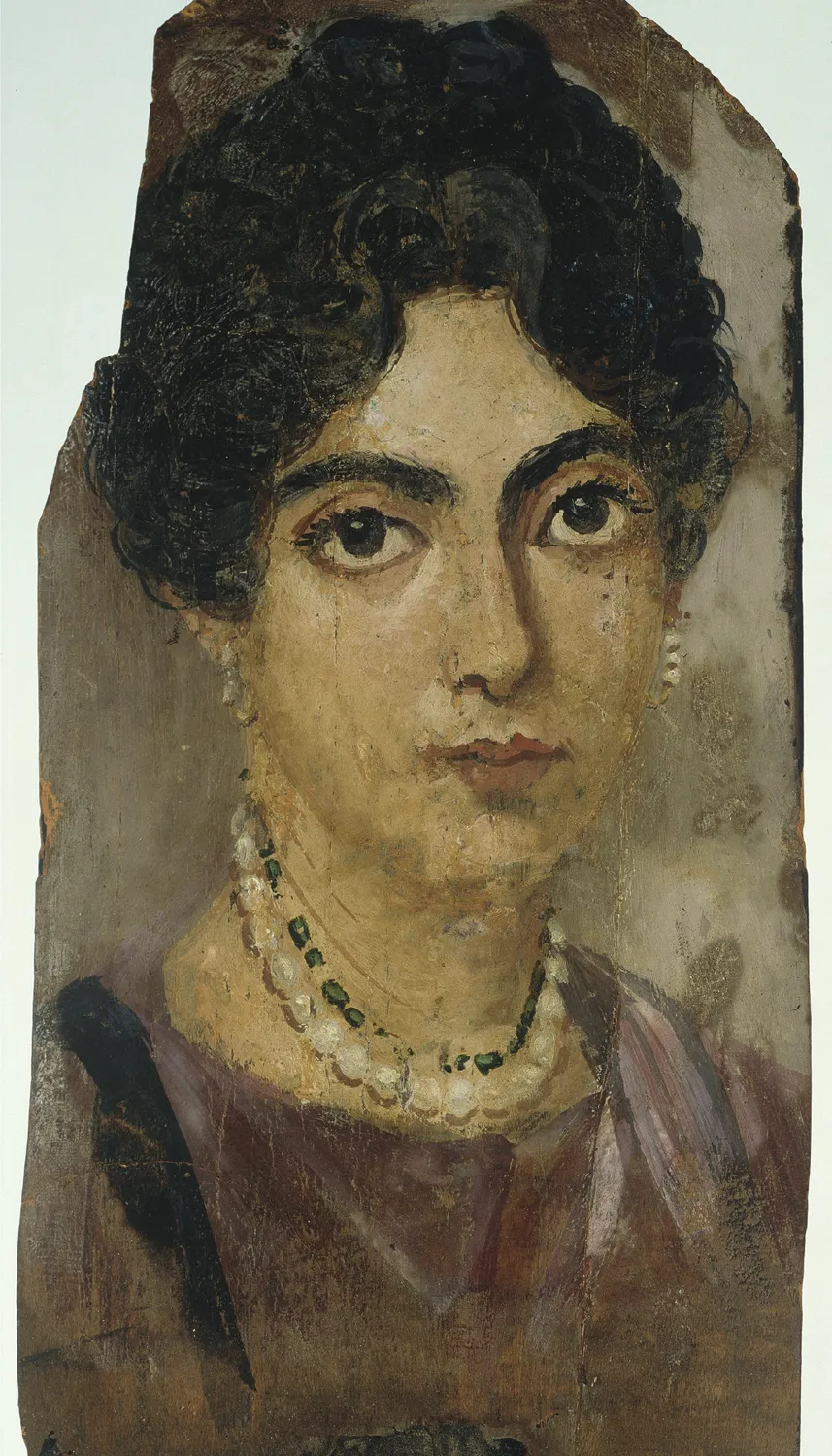

If, however, we want to have a larger appreciation of the relevance of the painted portrait today, we might have to look beyond notions of the individual, beyond reality television or the Renaissance for a precedent. The earliest painted portraits to survive in any number are the so-called Fayum paintings. Although the practice of interring funerary masks with mummies dates much further back, the Fayum paintings were made during the first and second century AD and were found in necropoles in Egypt at the end of the nineteenth century. These paintings, just like Holbein’s painting of Christina of Denmark, were functional. The art critic and novelist John Berger assigns two distinct functions to these haunting paintings. The first is as a memento for the family and friends of the deceased during the period of embalming, which could last seventy days. The second function Berger likens to a passport photograph, preserving identity during the journey to the Kingdom of Osiris. These paintings were ultimately not for popular consumption, as they were buried with the corpse. They represent an attempt to preserve tangibly both the likeness and the soul. I can’t think that the two terms, likeness and soul, are synonymous, but the relationship is established and complex.

These faces are not detailed records in the way that the Robert Campin portrait seems to be, but they are often so direct and vivid that one is entirely persuaded of the presence, the reality of the person. I think contemporary portrait painting has much to do with this association of likeness and soul. We might shift to a different vocabulary, preferring perhaps ‘presence’ or ‘essence’ to the word ‘soul’, but the association is there. Portraiture might today still be perceived as some measure of a person’s importance in the world, a token of their celebrity, but contemporary portrait painting is very often more layered; like the Fayum pictures, painted portraits today typically depict private individuals, not pharaohs or soap stars, but people who are precious to a relatively small number of intimates.

When I saw Daphne Todd’s painting of her dead mother, I was astonished. We live remotely from death and coming upon such a tender and real representation in the National Portrait Gallery was shocking, wonderfully shocking. There was nothing remote there, nothing hidden or harsh. The bare torso seems bereft, a testament to the departed life, a delicate husk. We know this is a painting made from life, whereas we don’t know whether the Fayum paintings were made posthumously or not. Woman With a Double Strand of Pearls is so seemingly alive, however, and Last Portrait of Mother so seemingly dead, that it seems both paintings delve into the same moment, splicing together now and then, death and life.

The painted portrait is not an anachronism, even though it is now so much easier to represent reliable and sometimes startling realities with a camera. The means to make extraordinary visual records have been mass-produced and made very affordable. We can all have the tools to make pictures with the detail and moment of an Ingres. These tools are, of course, managed more successfully by some than others. We are enjoying a technological endowment which gives every one of us the capability of producing extraordinarily vivid and precise images. With little or no apprenticeship we can become pictorial craftsmen with fabulous technical capabilities. Skill has become a commodity, a very affordable commodity, and possibly, as a consequence, has been devalued. This may be in part the reason why we still turn to the unique, hand-crafted portrait, because in its very form it remains a metaphor for the uniqueness of the individual depicted. It may be that when we move oil and pigment around on a piece of linen with the intention of making a likeness, we are still trying to do exactly what Rembrandt did, sliding paint into truth. Perhaps portrait painting is such a consistently human activity that both Robert Campin and Rembrandt would know exactly what we are about. It is certainly true that a well-painted likeness is special.

Art or Craft?

Portrait painting, then, is an enduring and popular art form. There is...