- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

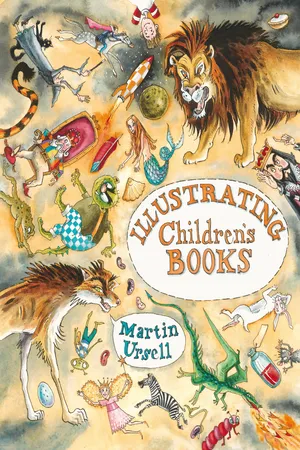

Illustrating Children's Books

About this book

How do you go about illustrating a children's book? Where do the ideas come from? How do you illustrate a narrative? How do you get published? This beautiful book answers all these questions and more. With practical tips and ideas throughout, it explains and follows the journey from first idea to final completed book. It is filled with illustrations that show how these images are made, and offers a rare chance to see the roughs, visuals and ideas sheets from a variety of childen's illustrators. Exercises support the ideas discussed and suggest ways of developing them. A beautiful book aimed at artists, illustrators, publishers, colleges and adult education courses teaching illustration. Explains the journey from first idea to the final completed book. Offers a rare chance to see the roughs, visuals and ideas sheets from a variety of children's illustrators. Superbly illustrated with 199 colour images. Martin Ursell is a senior lecturer in illustration at Middlesex University and has illustrated many books for children.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

- A story based on a window, door or portal into another world. For example, Alice in Wonderland, The Narnia Chronicles, The Subtle Knife.

- An untrustworthy character who tricks or gets the better of the other characters. For example Brer Rabbit, Mr and Mrs Pig’s Evening Out.

- A child who is mistaken for someone else.

- A character who is lost, either literally or metaphorically.

- A dream world where on falling asleep the character is somewhere else.

- The character having a fear of something that is resolved by the end of the book. They are shy, small or different.

- A riddle or a puzzle that needs solving. For example, Where’s Wally?, The Ultimate Zoo.

- Dealing with a catastrophe or disaster.

- An inanimate object that becomes real. For example, The Velveteen Rabbit, Pinocchio.

- A powerful being or monster that the child helps, with the result that they become friends.

- Curiosity, good or bad. For example, Pandora’s Box, Curious George.

- Dealing with a strange or eccentric family member.

- A magic implement or a spell that seems marvellous, only to end in tears. For example, Sparky’s Magic Piano, King Midas.

- A story about sharing, either with a positive outcome or a negative one. For example, The Fiends, The Dog in the Manger.

- A character taken out of their element to experience the consequences. For example, The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, The Fox and the Stork.

- A vice or bad habit that leads to problems. For example, The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes.

- A chain of events where one thing leads to the next like a series of consequences.

- A chosen one or special child. For example The Sword in the Stone, Harry Potter.

- Beginning with an idea based on personal experience is a good start, maybe an episode or interesting adventure; write it out or draw it out as a storyboard, exactly as it happened. Now look at what you have and re-imagine those parts of the story that are dull or unnecessary – remember you do not have to keep to the facts. Think of it like retelling an anecdote: in order to make the story more interesting one often exaggerates a little or embellishes a few details. Try doing this with your visuals. In the same way, when one is recounting a story verbally one might want to give the characters different voices, or talk faster or louder at particular points of your tale. One can do the same thing with visuals by drawing lots of small drawings instead of one large image, or by choosing a bold dramatic angle to illustrate and emphasize a particular character’s action. When starting an idea the thing is to try everything. Explore and experiment all the time and try not to settle for the first image that comes into your head. It often seems like this is the best image one can come up with but there is almost always a much better idea just around the corner. This last point is extremely important and worth noting down.

- A joke makes another good starting point. It might need some work to turn this into a full picture book but on the other hand one already has the punch line to the story and this is often one of the most difficult things to resolve. As before, draw out your story in quick, simple visuals or roughs. At this stage try not to worry too much about using reference – this comes later; more important now is getting a feel for how one tells a story. Is it interesting and are you keeping the reader’s attention? Usually in a picture book one does not have many pages to tell the story so every word and image has to count. When beginning ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- Chapter One: HAVING AN IDEA

- Chapter Two: SKETCHBOOKS

- Chapter Three: STARTING A BOOK

- Chapter Four: DEVELOPING A CHARACTER

- Chapter Five: THE DUMMY BOOK

- Chapter Six: MEDIA and MATERIALS

- Chapter Seven: THE ARTWORK

- Chapter Eight: OFFERING your book for PUBLICATION

- Chapter Nine: LONGER STORIES

- Chapter Ten: THE PROFESSIONAL ILLUSTRATOR

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app