![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE INSECTS AND THEIR RELATIVES

The insects and their close relatives – the arachnids, centipedes, millipedes and woodlice – make ideal material for microscopic study by the recreational microscopist.

If you wanted to look at bacteria, for example, you need very high magnifications and top notch equipment to see them under the microscope; also to visualize a bacteria, the scientist must use a multi-stage staining process, even for temporary slides, not to mention the safety issues of culturing bacteria and the chemicals required. With the insects however, even at low magnifications using a small hand lens opens up a new world of detail when viewing even the most common of insects. If you take the time to prepare and slide mount an insect you can see the tiniest details of animals barely visible to the naked eye.

Insects are the perfect size for study, only requiring low to moderate magnifications. This size means that you can get by with only modest equipment. A stereo microscope and a simple compound microscope form a more than adequate starting point. Some might argue that all you need to start is a good ×10 hand lens, or watchmaker’s eye piece; however the aim of this book is to foster a love of microscopy, so it can be assumed that by picking up this publication the reader is moving beyond the realms of the simple lens.

Those that study insects are call entomologists, and the workhorse of entomology is at least one microscope; normally an entomologist will have at least a stereo microscope, usually with the ability to expand the range of magnification. Sometimes the stereo microscope is supplemented with a high power compound microscope (see Chapter 2).

Insects offer a number of advantages, other than size, to the recreational microscopist. You can start with either exotic ‘gift shop’ style insects normally embedded in a clear resin which are great to look at under a stereo microscope at low magnifications, or you might begin with prepared slides of insect parts available from most microscopy suppliers.

Fig. 1.1 Examples of the types of specimens that you might have seen available in stores, or even might own yourself: a framed riker mount, and a specimen encased in Lucite resin.

Fig. 1.2 Blackfly aphids covering a tree in Nottinghamshire.

Fig. 1.3 The harlequin ladybird (Harmonia axyridis): a species of ladybird beetle, invasive to the UK.

You can then move to observing specimens from the garden live, or dead specimens found around the house (normally on windowsills). If you prefer you can purchase cultures of insects, either the types sold as food for exotic pets, or maggots sold as fishing bait. You can collect wild specimens using a number of techniques – a cursory glance at these techniques is provided in this chapter – although a full book can be written on collection techniques, and in fact a great number have been! I have endeavoured to provide a starting point as well as an idea where to find further information should you wish to pursue field work in more detail.

BUYING INSECT CULTURES

The most common insects available as food for exotic pets are crickets, locusts, waxworms and mealworms, in both small and supersized. Most of these are not native to the UK and as such should not be released into the wild, and those that are native to the UK tend to be pest species, and as such also should not be released. If you have an exotic pet, the disposal of live cultures is quite simple. You can also pop the specimens in the freezer overnight to euthanize them prior to disposal, or use an appropriate method as discussed later.

What is an ‘insect’?

It would seem wise to start by considering what we mean when we say insects. Often the term insect is used interchangeably with ‘creepy crawlies’ and ‘bugs’. Strictly speaking ‘bugs’ refers to close relatives of the aphids, rather than just insects in general. When you begin the study of some form of natural history you will probably find yourself confronted with a whole new collection of jargon associated with the field of study. Often the beginner will say ‘but I just want to learn the common name’, which will irritate some in the field. However I still remember when I started and the steep learning curve that I had (even after I had completed a degree in ecology!) An unfortunate fact of life is that the knowledge of insects is sadly lacking; most insects do not have a common name, and sometimes a common name actually refers to a number of species (for example, a greenbottle fly could refer to any one of the Lucilia, of which there are seven UK species).

Fig. 1.4 A flesh fly (Diptera, Sarcophagidae); despite the common name of the family, many species are not flesh eaters, while the species that do eat decaying animal flesh are used to determine time of death in cases of forensic importance. The Sarcophagidae often require examination of the genitalia to correctly identify specimens.

Attitudes towards the insects do not help. If you were an expert in say pandas, the world does not expect you to know much about a blue whale for example (both are part of the mammals), but if you are an entomologist who specializes in dung beetles for example, the world will say ‘I thought you were an expert?’ if you cannot speak at length about the dragonflies. Given the vast number of insects compared to any other form of animal on the planet it is laughable that anyone could possibly know every species! Most simple field guides (the kinds with photos to compare to rather than text descriptions) only consider the most common species (often not mentioning similar species) no matter how ‘complete’ they claim to be.

Classification

Barnard (2011) described the classification of the natural world as a vital instinct that allows the human race to study the world around it. Selecting to read this book implies that the reader has at least an interest in both ‘creepy crawlies’ and microscopy to a degree. But to start with, it would seem best to explain what these ‘creepy crawlies’ are. By and large when ‘creepy crawlies’ are mentioned we think of insects and their close relatives in the Arthropoda, and sometimes if the definition is stretched to its limits the ‘worms’ and other invertebrates are included. The aim of this book is to deal primarily with the study of the insects and their closest relatives by use of the microscope.

To understand where the insects and their relatives sit in terms of classification of living organisms we must first understand a little about how organisms are classified. Traditionally biologists use a system of divisions called taxons (Campbell et al.,1999).

Taxons are arranged as follows:

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

A species is an individual group that are capable of breeding and creating viable offspring, A kingdom is one of the largest divisions of life, in this case the animal kingdom. However there are some researchers that consider there to be divisions above kingdom (Campbell et al., 1999) and there are some subdivisions of the taxons presented above.

To describe the many varied types of insect would require a least a book to itself, where as to describe every individual species of insect one would require a full library of books. In Britain alone there are 24,043 species of insects that have been described and 1,011,740 species worldwide that we know of (Barnard, 2011).

The insects are defined by Chinery (1993) as having a body divided into three regions, a head, thorax and abdomen. The head has a pair of antennae, and the thorax has three pairs of legs, and the wings if present. The presence of the three pairs of legs gives rise to the alternative name for the group the Hexapoda, which loosely translates as ‘six feet’ (Chinery, 1993).

Fig. 1.5 A blowfly showing the general diversion of an insect specimen.

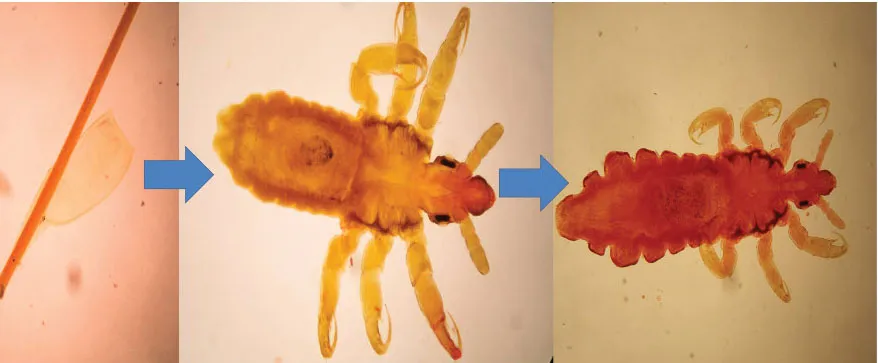

Fig. 1.6 An example of incomplete metamorphosis: the head louse lifecycle showing the egg stage (a nit stuck onto a human hair), the immature nymph and the adult.

SAMPLE CLASSIFICATION OF INSECTS

In the case of an organism, say a bluebottle fly (Calliphora vomitoria), this would be the classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Diptera

Family: Calliphoridae

Genus: Calliphora

Species: Calliphora vomitoria

The Arthropoda are a phylum (the first subdivision of a kingdom) of the animal kingdom, with the name Arthropoda being derived from the jointed limbs common to the phylum (Chinery, 1993). All are typified by the presence of a tough external skeleton (exoskeleton) made of chitin which serves both to protect the animal and to provide penetrating power within the mouth parts (Snow, 1970). Joints of this hardened exoskeleton are made of a softer cuticle known as arthrodial membranes (Snow, 1970) which allow the animal to move. The Arthropoda phylum contains a number of groups, such as the crustaceans including the woodlice and shrimps, the myriapods such as the millipedes and centipedes, the arachnids and the insects (Chinery, 1993).

Insect life cycles

Generally speaking insect life cycles can be classified as either ‘incomplete metamorphosis’ or ‘complete metamorphosis’.

An incomplete or hemimetabolous metamorphosis is that when the immature insects look much like the adults but smaller when they emerge from their eggs, and without wings. The immature stages are incapable of reproducing, and called ‘nymphs’ which often occupy the same biological niches as the adults. Examples of insects that undergo incomplete metamorphosis are the aphids, crickets, locusts, dragon and damsel flies.

Complete metamorphosis is where the adult and ...