eBook - ePub

Farm and Rural Building Conversions

A Guide to Conservation, Sustainability and Economy

Carole Ryan

This is a test

Share book

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Farm and Rural Building Conversions

A Guide to Conservation, Sustainability and Economy

Carole Ryan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Provides a detailed record of types of rural building and offers advice for conversion, including retention of period features where appropriate. Sympathetic conversion ensures that the record of rural life is not lost. Contents include; history and development of all types of farm and related buildings; conservation and planning issues; Local Authority guidelines; conservation professionals and ethics; the design process; budgeting; working within a rural context and landscape; and case studies. Farm and Rural Buildings offers a vital resource for owners and conservation and building professionals.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Farm and Rural Building Conversions an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Farm and Rural Building Conversions by Carole Ryan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture DesignCHAPTER 1

The Origin and Development of Rural Buildings

INTRODUCTION

The majority of rural buildings are tied in some way to the history of farming, be they those of the humble peasant, or those of the great landowning estates. Farming was the backbone of rural Britain, even in later periods when the Industrial Revolution appeared to hold sway over pockets of the countryside such as the Ironbridge Gorge, Shropshire. Even here farming was still practised as a by-trade to industrial activity.

The majority of historic farmsteads encompass the whole history of England in their siting, beneath their surface and encapsulated within their rural buildings. While it would be unusual for present sites to reflect the first settlers, reputed to be Neolithic, it is less uncommon for present-day farms to be in the vicinity of Iron Age enclosures, while some are set within the large enclosure of a small Saxon farming estate.

The most significant farm enclosure that may still reflect its original site is that of the manor house, which also operated as the demesne farm and was heavily defended. On the Welsh border, where invasion often met firm resistance, such defence took the form of a motte and bailey castle, the motte being surmounted with a timber keep, and the bailey the defended farmstead. Manorial enclosures around the demesne farms were often shared with the church, on a two-thirds/one-third basis. Such enclosures can be easily read from early estate maps, enclosure maps or tithe maps, and in many cases are still visible today.

The yeoman farms that replaced the manorial regime after the Black Death in some instances still survive today, their sturdy farmhouses, some still within moated sites (an early status symbol) having witnessed events such as the Civil War. They are still the heart of the working farm. Some may have been rebuilt in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and have lived through tumultuous events such as the Napoleonic wars, which in turn stimulated food production, and the enclosure of waste and common. This had major effect on the lives of the poor, who relied upon access to this facility for sustenance. The story continues with the tragic events of the two World Wars, the earlier being the most devastating, with the loss of thousands of farm workers who knew the land intimately but would never return to pass on their skills.

Saxon enclosure and Norman motte and bailey castle. The ridge and furrow field system is arguably the same date as the Saxon enclosure.

Mottes started life as conical, flat-topped mounds but time has eroded this example.

Farmsteads reflect a palimpsest of the history of England, not just great events but the people who lived through them, and whose farming lives, shaped accordingly, can be read through the buildings and the land.

PREHISTORIC TO MEDIEVAL TIMES

The true origin of the actual form of farm buildings will forever be lost to us. The first farmers are reputed to be Neolithic man because finds indicate that they started to settle in one place for longer periods than their nomadic prehistoric ancestors. They exhausted their immediate environment of food sources before moving further afield, though there is currently some dispute about this. Farm buildings may have consisted of simple enclosures of wattle with straw roofs. Iron Age round houses possibly show some affinity with these structures, and as weaving sheds and sunken food pits certainly existed, simple roofed enclosures for stock seem perfectly feasible. So-called Celtic fields echo the distribution of these dispersed settlements, as do the beehive huts to be found in the Celtic zones of Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The Romans would have had revolutionary farm buildings, if indeed they engaged in farming rather than marshalling the indigenous population to supply them with food, but apart from the villa itself, little evidence survives.

Corbelled fifth-century huts on one of the Skellig Islands off the coast of Ireland.

It is clear from archaeological finds that early Saxon farmers, themselves mercenaries brought in to try and fill the military gap left by Romans, were settling in fertile valleys such as those found in Dorset around the banks of the River Stour. The evidence from field names indicates a slow permeation into the heart of the countryside. Their successors, the mid- to late Saxons, left rather more tangible archaeological evidence (below ground) in the shape of their great feasting halls, surrounded by clusters of lesser rectangular buildings. These are the first tangible dispersed farming settlements, although many animals must have remained corralled but unsheltered.

It is in this late Saxon period that the open ridge and furrow field systems – attributed to medieval man – start to manifest. The basis of this was the feudal system of community-owned, oxen-driven plough teams, with military service owed to the Saxon theagn in return for strips in the open fields. Also known to have existed is the three-field rotation with winter corn (wheat, barley, oat and rye), spring corn or peas and beans, and a fallow field. Livestock consisted of horned cattle, which not only supplied meat but also leather and power as well as the all-important manure, implying that the farming cycle of ‘cattle who make the manure, which grows the crops, which feed the cattle (and humans)’ was well understood.

Such beasts would have required some shelter, and many linear village streets appear to have acted as over-wintering pounds, not just for cattle but sheep also, especially at lambing time, when protection was needed against wolves. The Welsh hafod, the farm associated with summer pastures but abandoned in winter extremes, indicates the importance of shelter for animals in winter. The earliest surviving aisled halls also indicate that cattle spent a goodly part of the winter indoors, at one end of living quarters for the upper echelons of society. Lowly farmers possibly had a lean-to roofed shelter at the end of their humble one-room dwelling, and these could be the precursors of a surviving Dorset feature that continues the end hip over a building whose usage may be for cattle housing or workshop; indeed, this was an arrangement that continued into the early twentieth century on the Welsh border. Cattle were also slaughtered and salted as their survival was dependent upon hay, which in a very wet or dry spring would have been in short supply.

Dorset gabled and timber clad outshot, once ubiquitous and now dwindling due to pressures for extensions. The use may have been agricultural or workshop.

Pigs were free spirits, occupying the woods, and living off beech mast (nuts of the beech tree), acorns and grubs. Like wild boar, they were not in need of shelter. It was only as the amount of woodland decreased, due to a slash and burn policy to retrieve agricultural land, that pigs eventually came into the farmyard.

Generally, in the late Saxon/early medieval period the need for farm buildings was limited, which raises the question of where corn was stored and threshed (beaten to remove the ear of corn from the husk). Threshing may have taken place in the cross passage of long houses (dwelling one side of the passage, animals the other) in the earliest open medieval halls, the precursor of the country estates that were to generate their own brand of outbuilding in later centuries. The opposing doors would have enabled the husks (chaff) to be blown away after being thrown into the air in the winnowing basket (though doubtless much remained). Cross passages later assumed a symbolic significance, especially in southwestern England, where they are retained well into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, long after their importance for processing grain or indeed even for controlling the draught for the fire, had ceased to have meaning.

The remaining conundrum is where the un-threshed corn was stored. Thatched ricks were certainly the norm in the post-medieval period, and these may well have had earlier precursors, as early estate records seem to indicate. An eighteenth-century building account at Gothelney, near Bridgwater in Somerset, indicates that an early barn must have existed, possibly of the same date as the rest of the house, which has its origins in the late fourteenth and late fifteenth centuries. Gothelney was commissioned by a wealthy lawyer, possibly indicating that only the elite – including Norman and later lords of the manor or abbots/priors of abbeys – actually threshed corn (wheat, barley, oats or rye) on a large scale and only they had large barns. As for the houses of early yeoman farmers in the immediate post-Black Death period, little evidence survives before the fourteenth century.

Yeoman farmhouse still located within a moated site, photographed in the 1980s. Such a survival is very rare.

On large estates and certainly on those associated with monastic houses, the barns were typically very large, and often referred to as tithe barns, the local inhabitants having to give one tenth of their produce to their lords and masters. (It should be noted, however, that such buildings may not always have had this function, being merely large, economical repositories for scattered farmsteads.) In the same way, villagers had to take whatever corn they were allocated to the lord’s mill to be ground. Many had home-made quern stones to avoid this onerous requirement, which could result in short measure upon return of the finished product. Mill sites have their origin in the pre-Domesday period, though surviving buildings reflect many rebuilds.

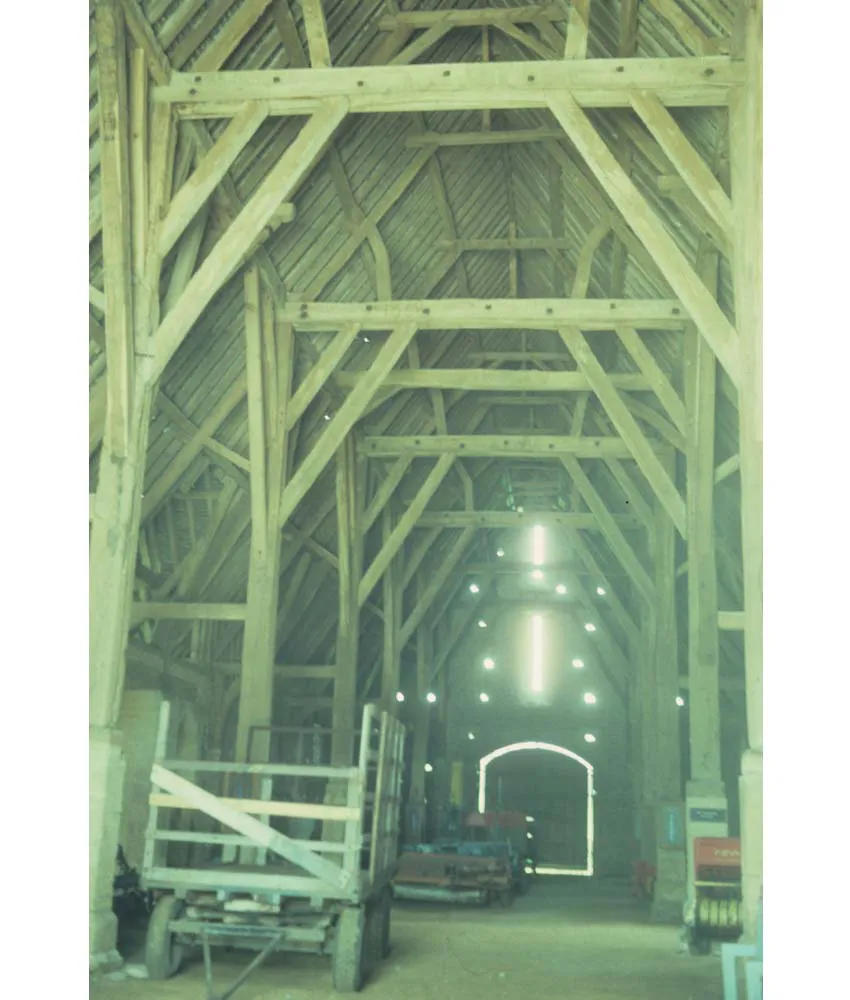

An aisled tithe barn.

Aisled construction gives a central nave and side-aisled format to buildings. In such barns the side aisles could be cordoned off with hurdles for stock.

Many barns would have had multiple uses, housing cattle and sheep in extreme winter conditions. Sheep were kept for their milk, the milk from cattle being sufficient only for their calves.

Drying corn sufficiently for it to be ground was a problem in damp areas of the country, and there is archaeological evidence for corn-drying kilns. In some areas corn may even have had t...