![]()

Chapter 1

WHY WE SHOULD USE TRADITIONAL MORTARS AND A BRIEF HISTORY OF THEIR DEMISE

The needs of old buildings are simple, but have been complicated and compromised by modern building technology and the mindsets and the materials that go with it. A building of traditional solid-wall construction needs to breathe; which is to say that the materials from which it was built were generally porous. More than this, they were effectively porous. Porosity and ‘vapour permeability’ alone do not necessarily express the effective porosity of the materials used originally, or for repair. This is the critical insight of David Wiggins’s research and the critical flaw in many eco or traditional building repair products, many of which are aggressively marketed and relatively expensive.

Traditional Building Materials

The materials from which traditional buildings were made were quite simple and straightforward: quicklime, earth, sand, animal hair, grasses and the by-products of other economic activity, such as brick dust, wood ash, forge scales, coal ash (in industrial centres). All were readily available, their relationships in use straightforward, and generally inexpensive. Most were locally sourced – most of the time – although the arrival of canals and, more especially, of the railways, saw materials spread further afield more readily from localized markets than had been possible by road or river transport. Even so, most of the materials used remained essentially local in origin, with more specialist materials – such as volcanic pozzolanic additives from Italy or from Germany – brought in as necessary and where they could be afforded.

Wood was a general, though by no means widespread, exception, with softwoods from the Baltic arriving from the thirteenth century at least. Their spread relied upon good ‘natural’ transportation networks – sea and river mainly – but also road where this was deemed essential or advantageous. Baltic lumber was routinely imported into Scarborough, North Yorkshire, from the 1300s onwards. Oak is rarely seen in the buildings of North-East Yorkshire, whereas in West Sussex, where navigable rivers were scarce, oak predominated well into the modern age. Species such as larch were imported to be grown for local markets, and imperial endeavour brought huge quantities of lumber from different parts of the world at different times, the extensive importation of Douglas Fir from the north-west coast of North America being one of the more obvious developments from the later nineteenth century.

Pantiles were initially imported from the Low Countries into North-East Yorkshire, but by the later 1730s were being made locally. Bricks, too, were imported into eastern England from Europe, though soft and very porous bricks were being made around Hull from at least the thirteenth century. For larger projects they were increasingly being made on site, along with the lime, as well as by commercial brick makers.

Malton, North Yorkshire, 1728. Painted by John Settrington. This is truly sustainable vernacular architecture. All of the materials of construction seen here were sourced from the immediate vicinity of the town: stone and lime from local quarries; bricks and pantiles from brickworks within or across the river from the town; earth for mortars from adjacent common lands; sand from the river or from nearby pits; thatch from nearby fields.

Traditional Building Practice

This book is an attempt to reassert the simplicity of traditional building practice and the relative simplicity, good sense and sustainability of traditional building materials, particularly of mortars, the ‘lungs’ and the ‘kidneys’ of any solid-wall construction. It seeks to celebrate craft and craft understanding, both of which came under increasing assault by a variety of often self-appointed ‘experts’, as well as by engineers, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, perhaps initiated some twenty years before, by Vicat, in France (see also Chapter 8).

From roughly the 1850s, the rise of the specifying architect (as opposed to the designing architect) began in earnest. Conscious attempts were being made by architects and other building ‘professionals’ to insert themselves into the building hierarchy over and above the craftsmen and craftswomen, particularly in the choice and specification of materials. This is made clear in many of the ‘expert’ texts of the time (Burnell, 1857; Scott, 1862). This was in part, of course, a response to the increasing complexity and ambition of construction, the increasing availability of less traditional materials such as cements and steel, and increasingly sophisticated transport networks. However, it represents a clear shift in the pattern of building that has continued to gather pace, and the consequences of which, for traditional vernacular fabric, have been generally negative.

Most of the buildings that craftspeople and conservators work on were not built to this pattern. Nor were they built with patented products, or even with ‘reliable’ products whose behaviour might be considered to be ‘always the same’, even when it is not (see The Problem with NHLs below). Instead, they were built to long-tested traditional patterns with mostly proven local materials selected by the builders themselves. The mortars were designed by the mason, bricklayer or plasterer using them, according to principles and preferences developed over millennia and passed from one generation to another – often without record beyond the buildings themselves – as well as to availability. These individuals often did not have scientific understanding of these materials, but they knew what worked and what did not. At the same time, they were able to respond to inevitable variability; mixing their mortars by ‘feel’, not by rote, and according to intended use. In the repair and maintenance of these structures, the building itself remains the most reliable specification, but is too frequently ignored, especially by the twisted mantra of making old buildings into commodities ‘fit for the twenty-first century’. This has seen far too many old buildings destroyed or debased, their essential character and performance compromised or removed in the spurious name of ‘saving’ them.

Modern construction, and its panoply of ‘value-added’ materials, is a function of industrialized capitalist production, not of traditional forms and relationships that have existed since time immemorial. Building conservation, and its associated ‘low-tech’ materials, respects the knowledge and experience of those who came before us. It tends not to assume that we ‘know better’, seeking instead to preserve the achievements and the monuments of the past and make them accessible and available in the present. In this sense, it has always been an anti-capitalist, even a socialist, enterprise, consistent with the political perspective and ambition of one of its primary advocates, William Morris and the organization he founded, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings:

Believe me, it will not be possible for a small knot of cultivated people to keep alive an interest in the art and records of the past amidst the present conditions of a sordid and heart-breaking struggle for existence for the many, and a languid sauntering through life for a few. But when society is so reconstituted that all citizens will have a chance of leading a life made up of due leisure and reasonable work, then will all society, and not our ‘Society’ only, resolve to protect ancient buildings from all damage, wanton or accidental, for then at last they will begin to understand that they are part of their present lives, and in part of themselves. That will come when the time is ripe for it […] Surely we of this Society have had this truth driven home often enough, and often had to confess that if the destruction or brutification of an ancient monument of art and history was ‘a matter of money’, it was hopeless striving against it. Do not let us be so feeble or cowardly as to refuse to face this fact, for, for us also, although our function in forming the future of society may be a humble one, there is no compromise.

(Architecture and History, 1884)

In Malton, documents illustrate not only the pattern of building from the earlier eighteenth century until the end of the nineteenth century, but also the changing relations of their production. An agents’ Memo Book spanning the years from 1733 to 1808 (NYCRO ZPB III 5–2–1) clearly demonstrates that, throughout this period, the masons (or carpenters) controlled the choice and design of the materials to be used. The Memo Book contains numerous small contracts between the estate that owned most of the town and the craftsmen. The work was carried out according to mutually agreed measured rates. Whilst the composition of the team might vary, in all cases the agreement is signed by all of those scheduled to work on a building, indicating that all would be paid the same rate, though some might earn more than others by producing more work on any given occasion. There is minimal specification, most of it relating to the proposed dimensions of the building.

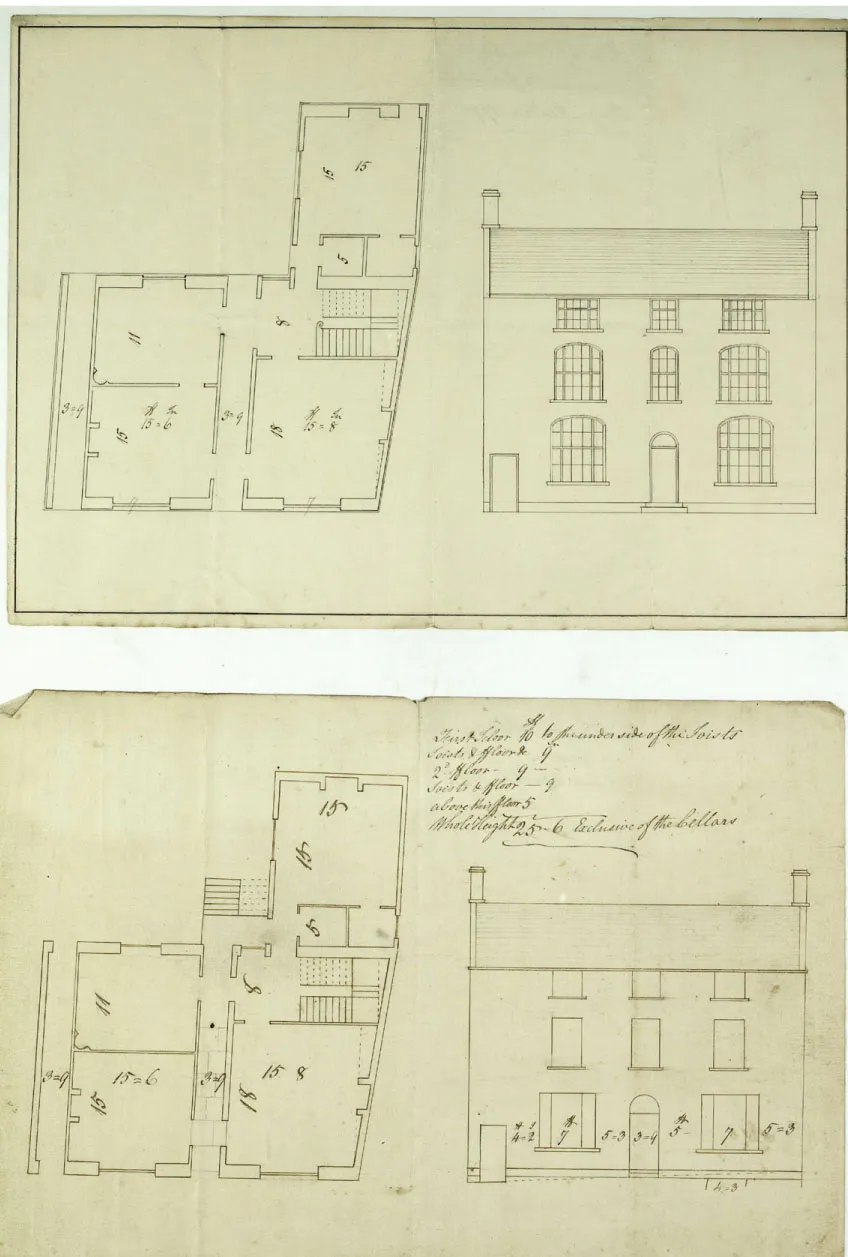

During much of this period the building mortars were still of earth-lime, with lime pointing and finish plastering. The contracts call for the ‘best mortar’, with the lime typically supplied by the estate from kilns that it owned. Other documents from the latter years of the eighteenth century, and not included in the Memo Book, are more thoroughly detailed by the estate agent, but the mortars are not specified in any detail at all. The specifications reflect the general pattern of vernacular construction at the time. It is agreed that if the estate is unhappy with the work (or the mason unhappy with his treatment by the estate), then the work will be inspected and judged by a fellow craftsman on behalf of either. This indicates that the co-operative culture among masons and carpenters in the town, illustrated by the Memo Book, endured at this time. Other documents from this time are proposals from individual masons for the construction of new buildings in the town, accompanied with simple plans and elevations which they have produced.

Malton mason’s sketch for a proposed building. In this period, local masons proffered sketches before commencing work, though the final design might change as works progressed. (NYCRO ZPB III 9–6)

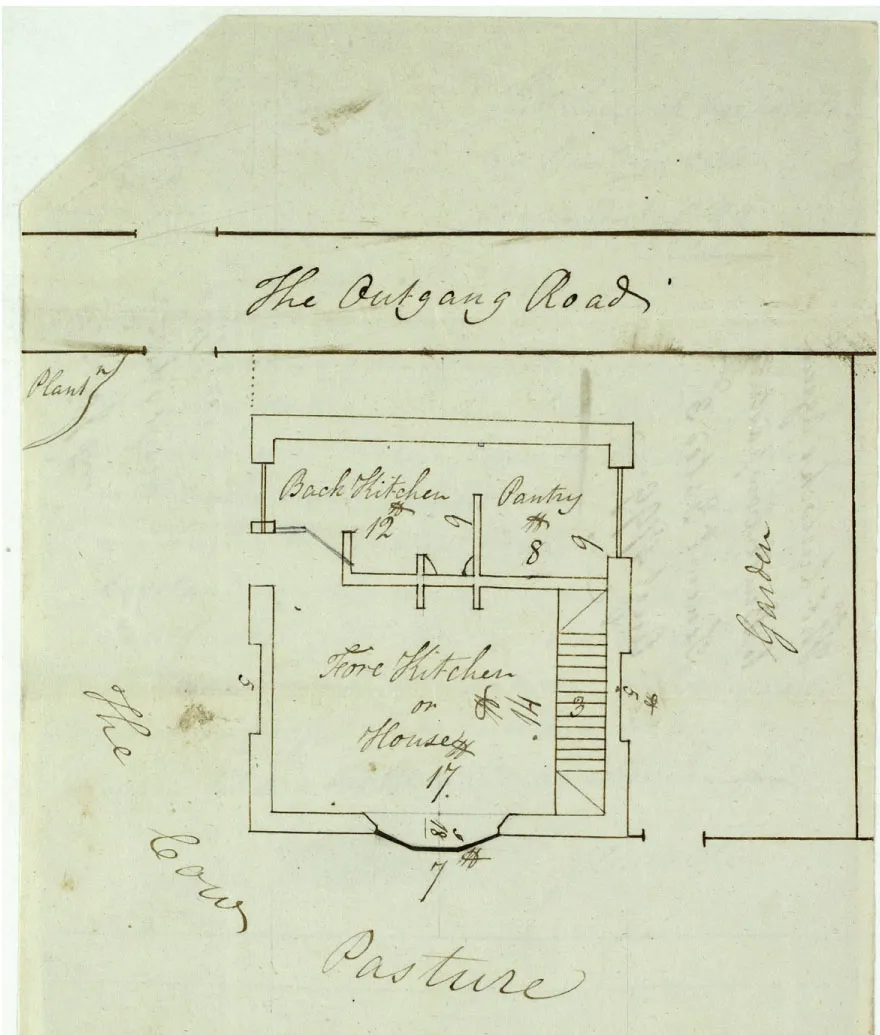

The same building proposed above, as it was constructed.

3rd Augt 1799. I agree to build a tenement in the cow pasture in Malton Fields according to the plan hereunto annexed or with such alterations as may be made therein before the building is begun at the prices within mentioned […] 6s per rood for walling stone; 1s 6d per rood for mortar without lime; 11s 9d without pointing; 12s 6d if pointed. (NYCRO ZPB 9–6)

This situation continues into the second decade of the nineteenth century, when architects begin to be more involved in the design of prominent buildings, but not in their specification. Building accounts survive which show the material and labour costs for particular buildings. The architect simply signs off the work. The first documentary evidence for the detailed specification of works and materials by the estate is 1846, by an architect (John Gibson). By the 1870s such specifications are, for the first time, being put out to competitive tender by the appointed architect. Without exception, the contracts are awarded to the lowest tender. Similar patterns may be seen in most archived building accounts around the UK, wherein specifications are scarce and rarely found before the 1860s, although where the workers are directly employed by rural estates (for example, Newburgh Priory), the traditional ways continue for much longer and most works are detailed mainly in daybooks.

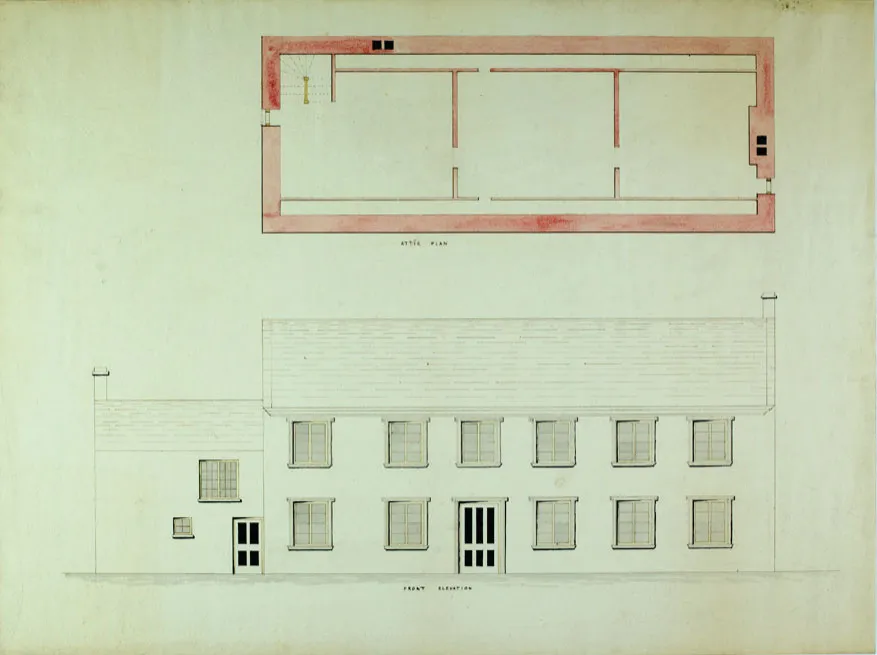

Architect John Gibson’s drawing of seventeenth-century Hunter’s Hall, Old Malton, prior to repair and conservation. Gibson called for the retention and repair of all structurally sound stone, called for repair over replacement and specified lime mortars throughout. His father had been the lead carpenter in Malton. (NYCRO ZPB(M) 7–49)

The buildings produced mainly by the masons and carpenters themselves, according to traditional patterns of construction, remain. The greatest threat to their survival, and to their proper performance, has not been the materials used in their construction, nor the practices of those who built them, nor the passage of time since. It is the imposition upon them of modern, incompatible materials, very often specified by expert professionals and applied by individuals disconnected from the general understanding and traditions of their forbears, whose minds have become clouded by the modern preference for hardness and apparent solidity and the over-rapid turnaround of any investment. All of them have been trained in a pattern of building technology that has only existed for around 100 years, the principles and materials of which may rarely be applied to buildings of traditional construction without detriment to the health of their fabric and to that of their occupants. Even if twentieth- and twenty-first century buildings, and the technology that designed and made them, were ‘better’ and more substantial, this would be a moot point in the conservation and repair of traditional buildings not built in this way, or with the same materials. This book is about some, at least, of the materials with which these buildings were constructed, and with which they should be repaired by those wedded to the principles of like for like and compatible repair, as well as carbon reduction.

Traditional v Modern Mortars

Traditional buildings need to perform as their builders intended (Oxley, 2003). This means that the mater ials of repair and conservation should be compatible. There is little better way to achieve such compatibility than to use the same materials that were used by the original builders, and to process them, where practicable, in the same way. In the case of mortars, to use the same materials, processed in the same way and used to the same or similar ends, will mean that we can have similar success with the buildings we work on. This will sometimes require patience and determination, and at other times entail partial or abject failure.

As will be demonstrated in the course of this book, most above-ground masonry construction, historically, was executed in earth-lime or in a pure or nearly pure, typically hot-mixed, lime mortar, rich in binder content, either in combination or discretely.

The ingredients of both mortars were locally sourced, relatively ‘weak’ and both met the essential criteria for building mortars. These were well known to masons and others and set down by Boynton and Gutschick in 1964: ‘Mortar strength […] is often greatly over-emphasised to the detriment of other essential mortar properties, such as workability, water retentivity, and bond-strength […] those builders who strive for high or maximum mortar strengths usually obtain inferior mortar for normal, abovegrade masonry construction […].

‘Before the advent of Portland cement in the United States (from 1886 onwards), all masonry mortar was a straight lime-sand mix that inherently possessed very low compressive strength. True, some of the lime produced was derived from impure limestone that had varying (but usually faint to moderate) hydraulic qualities; other pure limes were mixed with crude, unwashed sand containing clay that acted like a mild pozzolan with lime. Whilst both of the latter types of mortars possessed slightly more strength than the pure (‘fat’) lime-clean sand mixes, all would be regarded today as extremely weak in compressive strength (ranging between 50 and 300 psi (0.34–2.0 Mpa) in 28 days).’

Whilst some more energetically hydraulic lime mortars were used locally, in the absence of alternatives, most were used underwater and underground. Even in these cases predictable fat limes and pozzolan were more common as...