![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

WHY OBSERVE THE WEATHER?

Why watch and record the weather? Perhaps the best reason is that the weather and its impacts affect us all and that learning more about the weather and how to observe it can be both fun and instructive. Weather observing can be done photographically with a camera, in the form of a day-to-day diary with pencil and paper (or computer), or with instruments. No two clouds/storms/seasons are ever the same, so there is always something new to observe and something new to learn.

Many of the amateur weather observers that I know pursue weather-related activities, either for their work or as a hobby. The effects of weather can last:

•For a few hours (how heavy will the rain be and will I need an umbrella?)

•A few days (winter snowfalls or thundery floods might be examples here)

•Over the longer term (how hot was last summer and how did it compare with a typical summer?)

For those with an outdoor job or hobby, the weather can play a crucial role in day-to-day activities.

With some simple observations, you can begin to answer questions like ‘what is the height of that cloud base?’ or ‘why did the wind change last night as the humidity rose, after an otherwise fine day?’ You can begin to understand the peculiarities of the weather in your locality, or maybe predict the minimum temperature for tomorrow morning.

Having an even longer timescale, the subject of climate change is one that cannot have escaped your attention in recent years. Those with a long observational record (maybe twenty years or more), even from several sites, will be able to see the effects of climate change (particularly the rise in summer maximum temperatures) emerging from their own measurements.

Fig. 1. Deep cumulus clouds developing into thundery cumulonimbus clouds at Holdenby House, Northamptonshire. How warm and sultry is it today compared to yesterday? Well, your temperature and humidity measurements will help you find out. EDWINA BRUGGE

We are all familiar with weather forecasts, the production of which relies at the outset on millions of weather observations that help determine the state of the weather across the globe at all levels of the atmosphere. While the observations for these forecasts are taken, on the whole, by professional meteorologists (often with very expensive equipment, such as satellites), there are many amateurs for whom observing the local weather is a hobby. It can become an all-consuming passion as statistics build up over the months and years, records are broken and different extreme weather types are encountered and recorded. Indeed, the earliest weather observers were often amateurs, a phrase which in meteorology is used to denote a person for whom the weather is not their main source of income or profession.

Many amateurs can help make important contributions to the science of weather and to the provision of weather data by maintaining well-kept records. Indeed, since there is no longer an official weather station in my home town, I have been asked on several occasions for copies of some of my own records from my home weather station by the police (investigating local crimes), solicitors, researchers and individuals pursuing insurance claims resulting from storm damage.

Perhaps you’ll be lucky and see a tornado or a funnel cloud from a safe distance; maybe you’ll measure some 15–20mm diameter hailstones or witness some other extreme weather conditions.

Weather has been the main hobby of mine for some forty years now. Learning about climates in school geography lessons, it soon became apparent to me that conditions at the local Ringway (Manchester) Airport (daily data from there were published in one of the national papers in those days) were sometimes quite different from those experienced at my home, which was surrounded by a large garden and was located in an inner suburb of the city. Moreover, both sets of measurements often departed from those that might be expected based on climatology – and both differed (for various reasons) from those made in the centre of Manchester at the local (rooftop) weather centre.

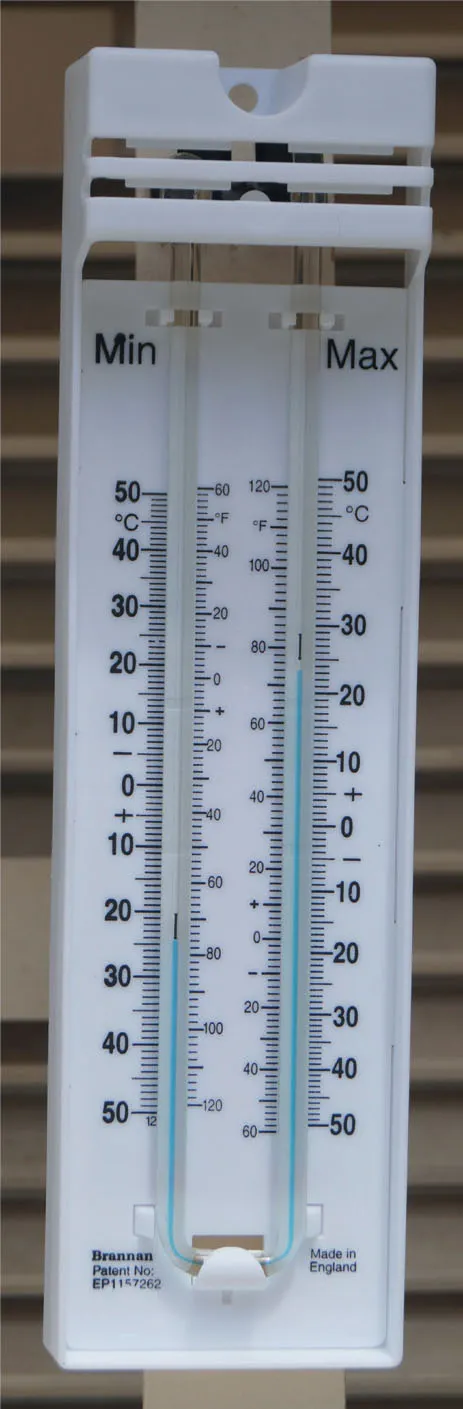

SIX’S MAXIMUM-MINIMUM THERMOMETER

Fig. 2. Six’s maximum-minimum thermometer. The minimum and maximum temperatures recorded since the instrument was last reset can be found by noting the value of the temperature scale at the bottom of each of the grey markers.

This thermometer (named after the eighteenth-century inventor James Six) is no longer used for the accurate recording of daily maximum and minimum temperature extremes, but is easy to purchase at most garden centres and can be found in many greenhouses as a result. The thermometer consists of a single U-shaped tube, the tubes usually being labelled ‘min’ and ‘max’. The bulb at the top of the minimum (‘min’) reading arm is full of alcohol; the other contains low-pressure alcohol vapour. In between these two is a column of mercury or, nowadays, mercury-free liquid.

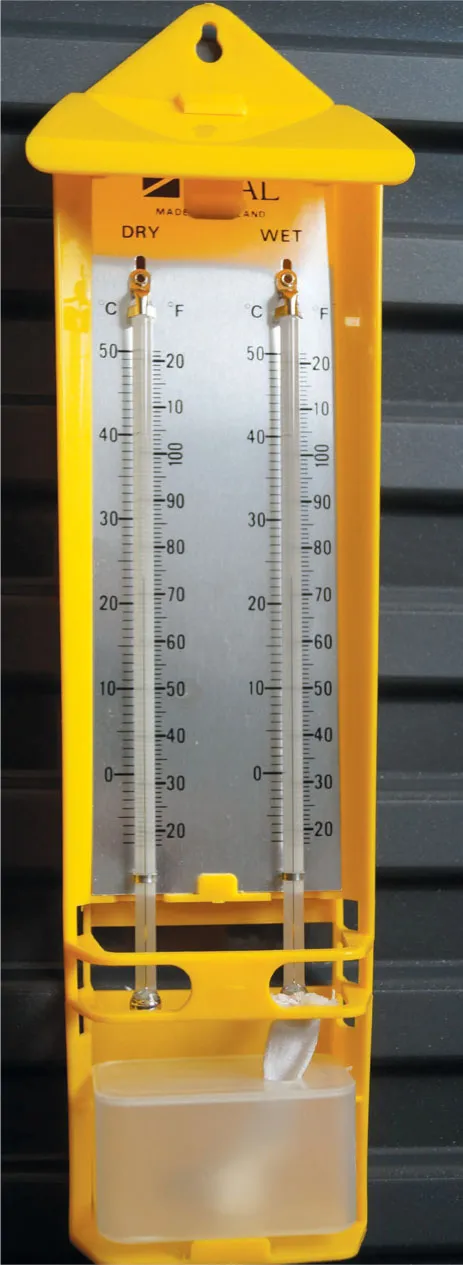

MASON’S WET AND DRY BULB HYGROMETER

Fig. 3. Mason’s wet and dry bulb hygrometer, showing the dry and wet bulb thermometers and the reservoir of water that feeds the wick surrounding the wet bulb.

The principle of Mason’s wet and dry bulb hygrometer dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, with the instrument consisting of two identical thermometers that are used to measure the temperature and humidity. As the name suggests, one thermometer is kept permanently wet by means of a tightly fitted sleeve that is wrapped around the thermometer bulb and draws water towards the bulb by capillary action from a reservoir of distilled water. The other (dry bulb) thermometer measures the air temperature. The wet bulb thermometer is cooled by evaporation and records a lower temperature than the dry bulb, the difference between the two readings being a measure of the humidity of the air.

Armed with a homemade raingauge (comprising a jar, plastic funnel and a measuring cylinder), a Six’s thermometer and a Mason’s wet and dry bulb hygrometer inside a homemade thermometer screen (made from louvred wooden walls mounted on an old tree stump), my early observations were to be the beginnings of a lifelong hobby. Being still a schoolboy at the time I began observing, and with weather being a scientific subject requiring technical (expensive) instrumentation, it was a few years before I owned what might be regarded as a ‘proper weather station’.

THE CLIMATOLOGICAL OBSERVERS LINK

The Climatological Observers Link (COL) is an organization of people who are interested in the weather. Its members are mainly amateur meteorologists, but many professionals and observers from schools, universities and research establishments also belong to COL. Many members run weather stations and keep records, ranging from daily rainfall and temperature measurements, with their observations and analyses maintained in log books or spreadsheets, to numerous weather parameters recorded every few minutes using elaborate electronic equipment, often displayed in real time on their own websites.

COL has published a monthly summary of UK weather since May 1970 – shortly after it was formed. This is largely comprised of the contributions of the members themselves, including summaries of their monthly weather observations and notes on the weather, and this is now the most comprehensive source of monthly weather information available in Britain.

COL also runs an online weather forum, as well as holding regular regional events and meetings for those with an interest in weather observing. More information about COL can be found on their website, www.colweather.org.uk.

Fig. 4. A report card as used during the 1980s to send thunderstorm reports to the Thunderstorm Census Organisation. By locating the direction of any lightning flash and then counting the time between the flash and subsequent thunder both the direction and distance from the observer of the lightning could be plotted. Assuming that all flashes came from the same storm, the movement of the storm with time could be plotted on the right-hand side of the card. AUTHOR/JONATHAN WEBB

However, these days weather observing equipment has evolved from the ‘traditional’ instrumentation that dominated weather observing around the world from about the 1850s (and in some places even earlier by a century or so) until late in the twentieth century. Now, one can buy reasonably priced electronic equipment via the internet or in local electrical stores in many high streets. Such equipment allows the keen amateur to monitor aspects of the weather continuously, rather than by just making one or two observations each day. There are also observations that can be made without resorting to instruments – observations, which, strangely enough, many modern-day professional systems cannot make.

Of course, once you start to observe the weather you may wish to share those observations with others. I spent many hours as a young observer watching the movement of thunderstorms across the local skies. Observations were made using special report cards, which were then sent to the Thunderstorm Census Organisation (TCO). Often this meant forgoing a couple of hours of sleep on thundery nights in the summer. Nowadays the role played by TCO has been taken over by the Tornado and Storm Research Organisation and there are also other organizations to which amateur observers can submit regular daily or monthly weather summaries and occasional reports of interesting weather events.

One such organization is COL, the UK’s Climatological Observers Link, which was formed in the 1970s by a group of amateur meteorologists. Many of the guidelines in this book are based upon the observing practices promoted by COL – thereby allowing observers to compare their observations with those of other sites, both amateur and professional.

BOOK LAYOUT

Hopefully, this book will draw you into the subject of weather observing using some relatively inexpensive equipment and encourage you to consider making ‘weather observing’ one of your hobbies.

The book is unapologetically aimed at those who are new, or relatively new, to weather observing. There is a lot about the science of meteorology that the amateur can learn from their own observations – and this book will give some insights and pointers here too.

Following this introductory chapter the book deals with setting up a weather station and then with observations that can be made without resorting to any instruments. Instrumental observations are then covered, in order of increasing complexity. Thus air pressure, rainfall and air temperature are treated first, with wind and soil temperatures, sunshine and evaporation following later.

For each observation type, some indication of ‘best observing practice’, what to record in your weather register, and the reasons for making the observation are explained.

Mention is also made of organizations and web pages, books and magazines that the newcomer to weather observing might find useful. Having made observations, many observers like to share their results and to see how they compare with measurements made at other sites, whether across town or on the other side of the world, or even with records made a hundred years ago; again some pointers are...