![]()

Chapter One

Conservation and Legislation

Background

Legislation to protect the UK’s historic buildings was first introduced in 1882. Although it took another century before legislation was enacted that would provide easier access for disabled visitors to these buildings, inclusive design is now a fundamental consideration whenever an historic building is being adapted, upgraded or remodelled.

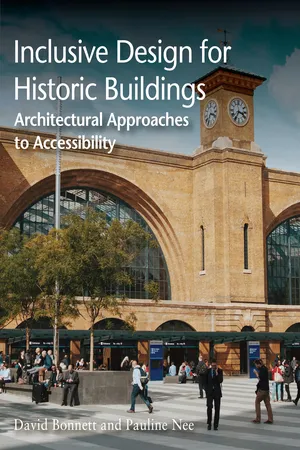

Sir John Soane’s Museum by Lincoln’s Inn Fields. (Photo: Tony Hisgett from Birmingham, UK, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The reasons for this change in attitude are varied: as disability campaigners became more vociferous in the 1970s and 1980s, public opinion shifted and started to regard access as a human right and a social expectation. Legislation followed the public mood, most importantly with the introduction of the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995 and the Equality Act in 2010. The 1990 Planning Act provided the green light for planning authorities to include access as a requirement in their development plans. Meanwhile, a requirement for access was introduced to the building regulations in 1985, albeit originally limited to new buildings and extensions to existing buildings.

There are over 500,000 listed buildings in England alone. Although a proportion of these will be uninhabited or function solely as tourist attractions, many are providing a similar function to that provided when first constructed, whether as a government office, a university, a place of worship, theatre, museum or train station. Politicians, office workers, students, theatregoers and passengers now expect to have full access to their place of work, study, entertainment or travel.

Financial considerations, unsurprisingly, have played a significant role in the creation of accessible environments. Building owners and managers may adopt the concept in order to minimize the risk – and potential cost – of being refused planning permission or building control approval. In other instances they will be keen to attract financial support from grant-awarding organizations. The Arts Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), among others, have made access a condition of their grant awards, resulting in the flourishing of high quality, inclusive design.

These financial considerations have been augmented by the growing significance of the ‘grey pound’ in sustaining ticket sales in historic venues throughout the country. The importance of historic buildings to both civic pride and to the UK economy leads to significant investment. One clear example of this is London’s West End, which has the highest concentration of theatres anywhere in the world; the majority are Victorian or Edwardian. The theatre district contributes around £1 billion to the UK economy. For tourism to flourish it is essential that no visitor to such venues be unnecessarily excluded. It is to be hoped that the 2020 pandemic does not have a long-term negative impact on the UK tourist industry.

The UK is deservedly proud of its international reputation for good access – as highlighted during the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. There is still a long way to go but the relative ease with which a visitor – whether in a wheelchair, using crutches, accompanied by a guide dog or with any other physical, sensory or intellectual disability – can now gain access to a large proportion of our historic buildings is testament to the determination and energy of various groups. The disability lobby, combined with the response of politicians, the resolve of funders, the open mindedness of the heritage lobby and the creativity of building professionals, have all contributed to the improving position.

The Role of Designers

The passing of the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995 required that the needs of all users should be considered from the outset. It was recognized that buildings must be designed and adapted in order to meet legal requirements and social expectations while achieving the highest standards of design. This aspiration for a creative response to access was expressed in 2006 by CABE.

The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 required building owners by law to ensure that where their buildings provided a service it should be accessible.

Each of the projects described in this book demonstrates that good accessibility requires a team approach, involving heritage specialists, building designers, operational managers and users. In many instances the way a building is managed will have the greatest influence on its accessibility. By embracing full access, providing clear information on the website, training staff, ensuring that specialist equipment is regularly serviced, and listening to feedback, all users – whether disabled or not – will benefit and hopefully appreciate their engagement with the historic environment.

The Response to Legislation and Regulation

The response of the statutory sector to the increased demand for access has generally been constructive, with the national heritage bodies, CADW, Historic Scotland and Historic England, together with a number of local authorities, producing guidance and providing training, as well as engaging creatively, on the whole, with campaigners, designers and others in exploring options for ensuring full access.

While design solutions have been wide-ranging – and we have probably all been disappointed by the insertion of a poorly designed ramp or a badly positioned platform lift – the professions have, on the whole, taken up the CABE gauntlet to deploy their creative and problem-solving skills in providing sensitive insertions or complementary additions to our best loved buildings.

The Houses of Parliament are a popular attraction for visitors, but are also working buildings with offices, the chambers and all supporting facilities.

Building owners and managers who may have baulked at the anticipated expense (frequently negligible) or the potential statutory objections (generally minimal) often become enthusiastic patrons of inclusive design. It is unknown whether this is because they are happy to see more diverse usage, whether it reduces the cost and aggravation of making specialist provision or whether it results in greater ticket sales, increased attendance at church or more satisfied employees.

Uniting Protection and Access: A Brief Introduction to Heritage Protection

The UK has long celebrated its wealth of historic structures. The Society of Antiquaries was set up as early as 1707, its aim, as set out in its 1751 Royal Charter, to foster ‘the encouragement, advancement and furtherance of the study and knowledge of the antiquities and history of this and other countries’.

In 1877 William Morris, with others, held the inaugural meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) and expressed concern that well-meaning architects were scraping away the historic fabric of too many buildings in their zealous ‘restorations’. SPAB continues to be a significant voice in the world of conservation, its philosophy of conservative repair and minimal intervention having a strong impact on heritage thinking. Five years after the creation of SPAB, the 1882 Ancient Monuments Act gave protection to twenty-one monuments and in 1895 the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments commenced its inventory of pre-1707 buildings.

In the early twentieth century, following the creation of the National Trust and other conservation societies, legislation was extended, often as a result of local campaigns. In 1947 the Town and Country Planning Act responded to the growing calls for adequate protection, instituting a statutory list of significant buildings and introducing the requirement for Listed Building Consent.

In 1983 the National Heritage Act created English Heritage (now Historic England) to protect and promote the historic environment: its equivalents in Scotland and Wales are Historic Scotland and CADW. The 2012 National Planning Policy Framework, updated in 2019, requires that planning authorities should recognize that heritage assets are an irreplaceable resource and conserve them in a manner appropriate to their significance.

Improving Access for All in Buildings of Historic Significance

It is against this background of statutory protection, combined with academic study and effective public campaigns to safeguard the nation’s historic legacy, that legislation to improve access for all was introduced toward the end of the twentieth century.

Despite the philosophy of minimal intervention in historic buildings, the demand for accessibility was accepted, and even welcomed, by heritage professionals. Many responded positively, providing both guidance and training. Details of key publications, produced by heritage specialists and others, are listed in the Bibliography.

The 2010 Equality Act, which replaced the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, provides protection from discrimination in the accessing of services in education and in employment. Those who have duties under the Act may need to adapt their premises to ensure that they do not discriminate. The Equalities Act does not specify design standards. However, service providers and employers may need to consider wider equality obligations when undertaking design work.

The requirement for accessibility does not override the need to obtain statutory approvals, such as Listed Building Consent, Conservation Area Consent or Scheduled Monument Consent. The importance of the historic fabric is summarized in the Building Regulations, Approved Document M, Access to and Use of Buildings, first introduced in 1985:

While full access is a necessary ambition, full compliance with access recommendations for some nationally important buildings may not be possible, or even desired. Where this is the case, it may be preferable to investigate options for mitigating access difficulties by providing high quality and creative visitor information, or exploring managed support.

Such an approach is very much the exception. This book will examine a variety of high profile buildings and their settings, many of them Grade 1 listed. Without exception, these demonstrate effective and welcome solutions to improved access. Acting responsibly, the architects and access consultants – as well as the clients, funding bodies and statutory authorities – were committed to retaining and enhancing the special interest of the building in question. It was recognized that when alterations were deemed necessary or desirable they should emanate from a thorough understanding of the historic and architectural significance of the facility in question. When such an approach is combined with an understanding of the needs of all users – and note that very few historic buildings have not been altered by the introduction of electricity or running water – these alterations demonstrate that it is possible to achieve elegant, effective and frequently understated solutions that benefit all.

An innovative approach can be of particular value when working with historic buildings. The most successful solutions are frequently the result of heritage advisors engaging creatively with access groups, designers and others in exploring options for ensuring full access. Such collaboration will ensure that our important historic buildings have a viable future, enabling them to function as working buildings as well as tourist attractions.

The approach to assessing the accessibility of an existing building is similar to the approach of conservation specialists who categorize the historic significance of each element of the building. It is not uncommon for intrusive elements that detract from the overall significance of a building to provide opportunities for the inclusion of access improvements.

As outlined in the introduction, the most creative solutions will fall short of expectations if the resultant building is not well managed. For instance, in an internationally renowned museum the beautifully designed accessible WC has a notice on its door advising would-be users to find an attendant to open it up. At a seminar on platform lifts, arranged for the benefit of Oxford colleges, facilities managers bemoaned not only the low cost and unattractive lifts that are frequently specified but also the maintenance contracts that employ lift engineers unfamiliar with non-standard lift mechanisms.

Access to a building commences when someone decides to visit and enquires about access provision, maybe by looking at the website or phoning for advice. A clear website, with advice on accessible transport options and car parking, as well as guidance on any barriers that may be encountered, is essential. Equally, ...