![]()

Chapter 1

Themes and Variations

THIS BOOK IS AN INTRODUCTION TO THE architecture of the Arts and Crafts Movement, one of the most exciting and influential artistic movements the British Isles has ever produced. The name was created by the lawyer turned bookbinder Thomas Cobden-Sanderson (1840–1922) who, in 1883, first coined the phrase ‘Arts and Crafts’. Little can he have imagined the influence the seemingly innocent joining together of these two words was to have. Yet the very fact that he, in common with many others, had abandoned a conventional and lucrative career in favour of ‘the simple life’ sought by pursuing the craft ideal of making beautiful and useful products with his hands that underpins the movement, is compelling evidence of that influence. Many people have heard of the Arts and Crafts Movement – most likely because of William Morris (1834–96) and his wallpaper designs. Some may even be aware of his famous saying, ‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.’1 The fact that he considered such a warning necessary was because in Victorian England the arts generally were in a state of turmoil as a new style for the century was sought.

Even a door can be a work of art – door handle and key escutcheon in Oxford University Museum.

William Morris, the leader of the movement, photographed by Edward Hollyer in 1888. When he died, his close friend Phillip Webb said, ‘I feel like I’ve lost a limb.’ (Scanned from J.W. Mackail, The Life of William Morris, 1899)

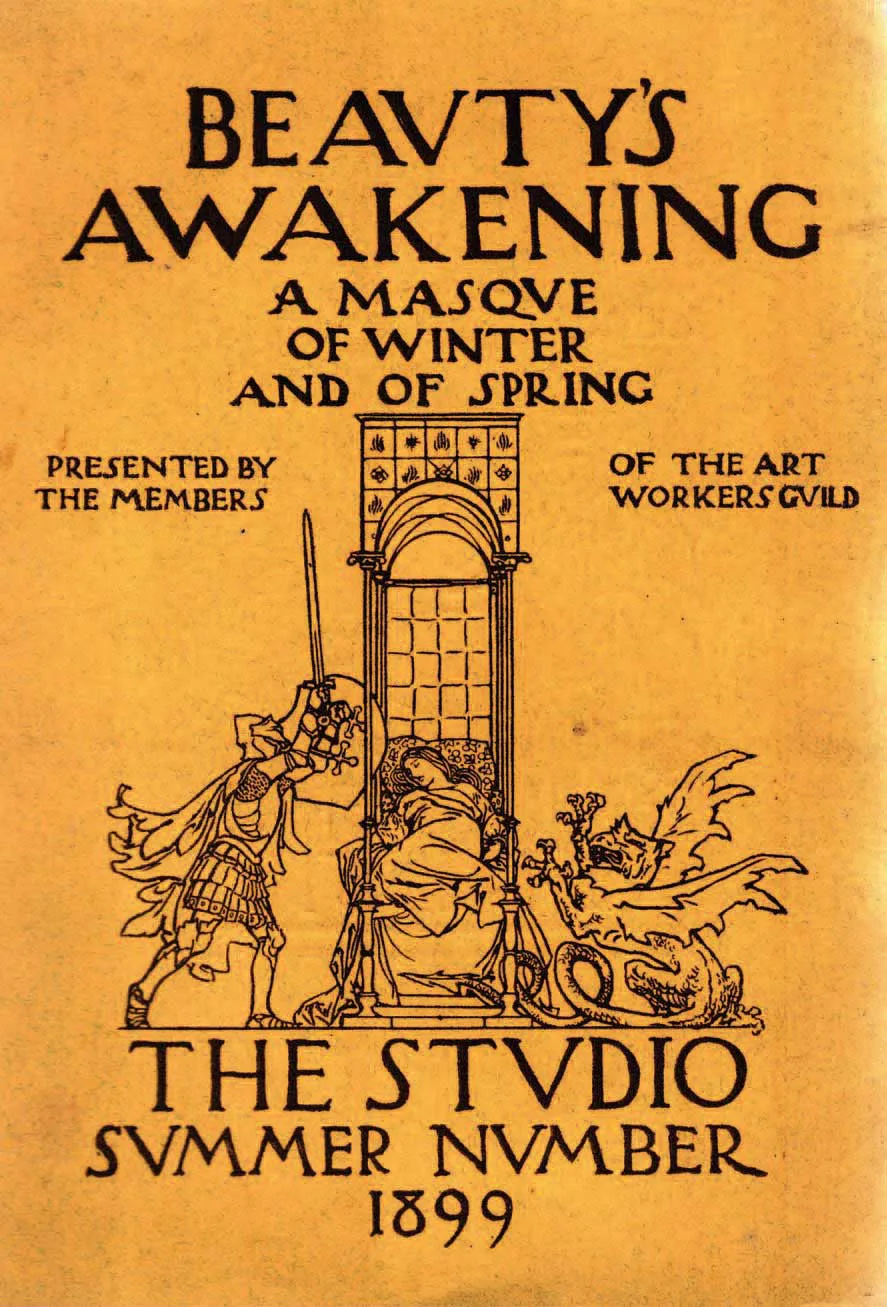

Front cover illustration by Henry Wilson for the programme of Beauty’s Awakening. It shows the knight, Trueheart, fighting with the dragon, Aschemon, over the sleeping Spirit of Beauty. (Author’s collection)

Beauty’s Awakening

Beauty’s Awakening, this book’s subtitle, refers to a type of fairy-story – a masque that was an elaborate and spectacular form of play with music. A mixture of Sleeping Beauty, Beauty and the Beast and similar stories, it was performed by members of the Art Workers’ Guild in 1899 in London. This guild is arguably the key organization of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Founded in 1884, the vast majority of architects and craftsmen discussed in this book were at one time or another members of it and membership is at least one convenient way of defining the movement. Like the medieval guilds it based itself on, it was a form of secret society of like-minded individuals – part trade union, part freemasonry – who shared an interest in reviving the crafts that were dying out in industrial Britain. First noticed in the 1880s, the movement grew to prominence in the 1890s and succeeded in exerting its influence well into the 1920s and even the 1930s. Opposed to the idea of the arts being about style, they created a new approach based upon regenerating society.

‘We want no style. . .’

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, one of the world’s first conservation bodies and a key organization of the Arts and Crafts Movement, put this issue of style well in its Manifesto of 1877 claiming that, ‘. . . the civilized world of the nineteenth century has no style of its own amidst its wide knowledge of the styles of other centuries’.2. For many, the burning issue of the day was what was this style to be?

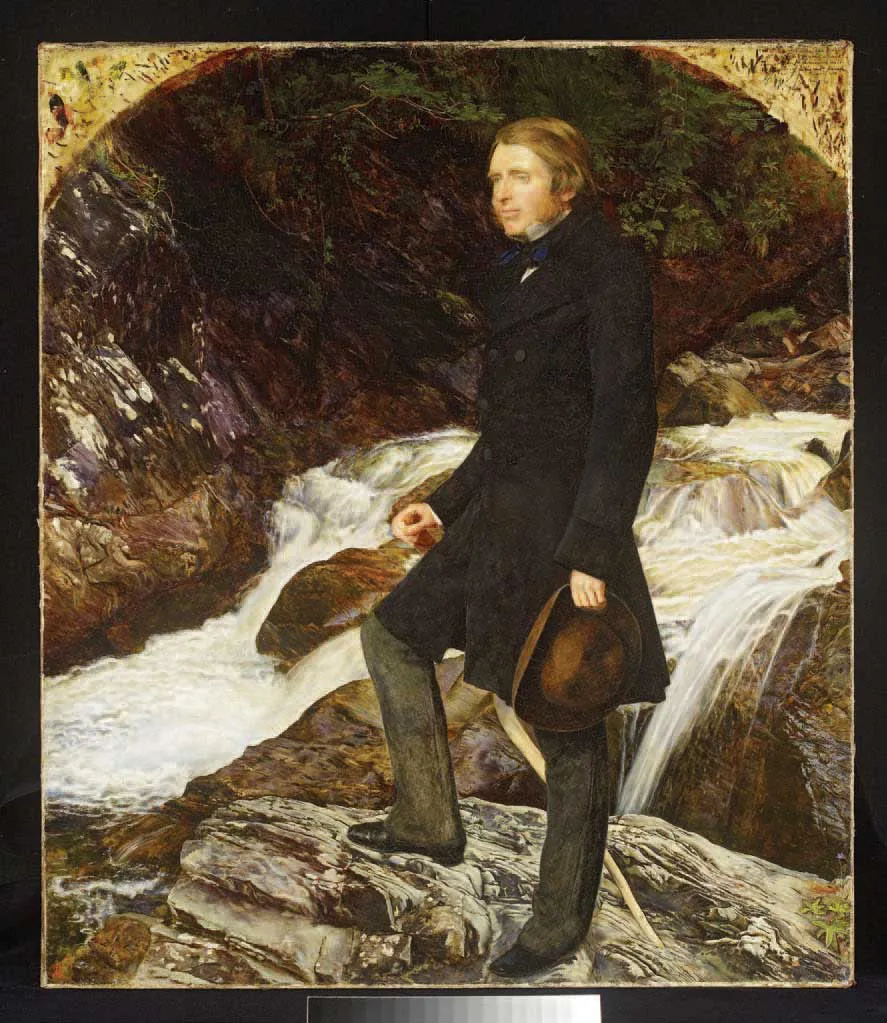

John Ruskin, the chief intellectual guide for the movement, painted in a vivid Pre-Raphaelite manner by John Everett Millais. (© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford)

However, the critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), the originator of so many Arts and Crafts ideals, argued against the whole idea of pursuing a style as the basis of architecture. ‘We want no style,’ he wrote, ‘. . . it does not matter one marble splinter whether we have an old or a new architecture, but it matters everything whether we have an architecture truly so called or not’.3 The architect E.S. Prior (1857–1932) was even more adamant: ‘Surely no style can help us,’ he wrote.4 To such men the search seemed pointless. Looking back shortly after the century ended, and to the succession of revivalist styles, another member of the movement, the architect Reginald Blomfield (1856–1942), lamented that, ‘Modern architecture seems incapable of progress except in a circle.’5

The Egyptian House, Penzance, demonstrates the extent of the British Empire and the wealth of styles available to copy.

An age of revivals

Architecture had reached the point that the only way it was thought of was as historicist, in other words copying the architecture of the past in an archaeologically accurate way. Archaeology, a relatively new discipline, was regularly accused of creating the conditions for revivalism by its desire to accurately record the remains of the past. The conflict, principally between the supporters of the Gothic Revival and those who favoured various forms of Classicism, came to the fore over the design of the new Foreign Office. George Gilbert Scott (1811–78) won in a Gothic Revival style – not dissimilar to the fantasy palace of railway hotels at St Pancras he built later – but the government, in the shape of Lord Palmerston, wanted Classical. Government won but not until a heated debate lasting many years gave the profession a bloody nose. We can perhaps get an insight into what it was like by reading the recollections of Charles Voysey (1857–1941), ironically the architect most associated in the public imagination with a recognizable Arts and Crafts ‘style’. Describing the average nineteenth-century architect, he recalled: ‘When a client called for a design the first questions asked were: What style do you want? Next: What period of that particular style? Given the style and the period, books were drawn from the library shelves and approved examples of details were chosen; a chimneypiece or chimney, an oriel, a door, or a window from several books. Such things as these were copied and welded together and like the ingredients of a Christmas pudding equally hard to digest.’6

The grand staircase of the Foreign Office by George Gilbert Scott. The key building in the ‘Battle of the Styles’, its Italianate appearance was a long way from his preferred Gothic. (Open Government Licence version 1.0, courtesy HM Foreign Office)

Accordingly, typical Victorian architecture might look Egyptian, medieval, Elizabethan, Italian, Greek, Spanish and so on but never modern, of its own age. Certain architects specialized in certain styles from the past; others were adept at moving from one to another without any sense of a style as something personal. Even architects who were supporters of the aims of the Arts and Crafts Movement, such as T.G. Jackson (1835–1924), built a career out of reviving past styles such as the Elizabethan and Jacobean.

The attractive gable end of Trinity College, Oxford, designed by T.G. Jackson. Looking every inch an old Jacobean building it was actually completed in 1885.

Situated in leafy Kensington, Webb’s London house for George Howard, the 9th Earl of Carlisle, and a great patron of the movement, was attacked for not conforming to a recognizable style. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Little wonder then that when Philip Webb (1831–1915) was designing No.1 Palace Gate, Kensington, for his wealthy patron George Howard (1843–1911), the 9th Earl of Carlisle, its design proved to be controversial as it was on Crown land and required special permission. Sir James Pennethorne (1801–71), the Crown’s advisor, sought advice from experts and was exasperated to find that none of them could tell what style the building was designed in! For Webb, the most important architect of the movement, that was a measure of success, and reminds us that our idea of originality is a very modern idea that would have not troubled most of our Victorian and Edwardian predecessors.

So it is important to state right at the start that the Arts and Crafts Movement, at its best, was not a style like others of the day, based on an archaeologically accurate understanding of their forms and decorative details and then copying them for modern buildings, but an approach, a collection of radical, progressive, utopian ideals that its followers – disciples even – adhered to.

In search of tradition . . . the timeless way of building

If these architects weren’t copying the famous styles of the past, how were they thinking of architecture? As a broadly based movement there was no agreed philosophy and no common document or manifesto that sets out its approach. Rather these ideals were concerned with creating a more humane, functional, simple, satisfying, and beautiful architecture based on examples found in the countryside built out of traditional materials by traditional methods. It was idealistic in seeing this as a way of combating the worst excesses of modern urban life in Victorian Britain, and maybe solving them by looking to a seemingly timeless vernacular architecture created by skilled local craftsmen – not professional architects.

Photograph of cottages at Chedworth, Gloucestershire taken from Old Cottages, Farm-houses, and other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber, published in 1905 by Batsford. Batsford were one of the new wave of publishers successfully exploiting the use of photography to popularize traditional architecture such as these attractive cottages.

The critic Lawrence Weaver (1876–1930), describing Ernest Gimson’s Stoneywell Cottage, said of it that it was ‘Roughly, even rudely, built… no tool has been lifted to mark a false impression of age. If it has the air of being old, it is only because old ways have been followed not because the least effort has been made to impart a false air of antiquity.’7 When a local returned to the area after many years away he was confused, as he didn’t remember the building – it looked as if it had always been there. This was a further measure of success for an Arts and Crafts Movement architect. M.H. Baillie Scott (1865–1945) was another of the architects who designed ‘. . . in different plac...