![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Pre-Railway Age

Earliest Times

Mining for coal in East Shropshire can be traced back at least as far as the thirteenth century, possibly to Roman times. The numerous bell pits and adits were already a feature of the area when the first tentative steps to railway construction were taken. In 1605, a wooden railway carrying coal from Broseley, via Birch Batch* to the River Severn at the Calcutts, was the subject of a dispute between James Clifford, lord of the manor, and his tenants Messrs Wilcox and Wells, who had built the line.

It is not certain when, exactly, the line was constructed. In 1604, the Wollaton Wagonway opened in Nottinghamshire, to carry coal from mines at Strelley to Wollaton, mostly for onwards movement by road to the River Trent. The Wollaton line is generally regarded as the first overland true railway in the world (more primitive wagonways in mines used plain wheels on boards, with pins and slots for guidance). Recently, there have been suggestions that the Broseley line may already have been in existence when the Nottinghamshire line opened – might Shropshire be the home of the world’s first railway?

Without further documentary evidence, that claim may have to remain unfounded. Huntingdon Beaumont, who built the Wollaton line, went on to develop primitive railways in Northumberland, where a horse would haul a single large chaldron wagon. The practice that developed in Shropshire was to haul several small wagons, coupled together – if not the first railway, then perhaps the first trains.

The Broseley dispute, heard in the Court of the Star Chamber, related to ‘A very artificialle Engine or Instrument of Timber … [consisting of] … fframes and Rayles.’ Today, the locomotive is the ‘engine’, but that description of the railway lives on in local memories. The oldest residents of Coalbrookdale may remember the ‘jenny’ or ‘jinnie’ rails’, which ran down the dale into the twentieth century. Several ‘jenny wagons’ have survived to be preserved locally.

Within a year or two of the dispute mentioned above, James Clifford had built his own (shorter) line from mines near Calcutts to the Severn and such railways soon became a feature of local mining. Parts of the original route may have been incorporated into the later line known as the ‘Jackfield Rails’, which also carried coal down to the river at the Calcutts.

In the early years of the eighteenth century, another coal-carrying line was constructed nearby, utilizing the valley of Tarbatch Dingle to descend eastwards to the Severn. In 1757, a westward extension connected the New Willey furnaces to the river, along a line of rails now extending almost 2.5 miles (4km). A junior partner in the furnaces was the notable ‘Iron-Mad’ John Wilkinson, who in 1787 launched the world’s first iron boat from Willey Wharf, the riverside terminus of the line. Much to the amazement of onlookers, it floated.

Just south of the Tarbatch line, the 1780 Caughley Railway connected to the Severn at Bagley’s Rough. Again, fragments of its route can be traced in the vicinity of Caughley Farm and Inett. West of Broseley, the Benthall Rails ran from quarries on Benthall Edge, where a small brick arch and a cutting may be remnants. A branch of this line (perhaps it was the main line) may have provided the New Willey furnaces with an alternative link to the river.

Clearly, there was much early railway activity south of the river during the 250 years prior to the coming of the main lines. Some of their routes (or parts thereof) can be proved, but some are conjectural. The first edition of the Ordnance Survey 1in map shows several ‘Rail Roads’, south of the river, including the Tarbatch line and the Benthall Rails, plus a line from quarries on Gleedon Hill, near Much Wenlock, to a wharf beside the Severn near Buildwas Park.

Early days at Blists Hill: the ‘Open Air Museum’ opened in 1973. In June of that year, wagons stand on the plateway beside Andrew Barclay-built Peter, whose career began at Kinlet Colliery in the south of the county.

North of the Severn

North of the river, on the same map, many more ‘Rail Roads’ are marked, along with the newly constructed main-line railways. (There is a gap between Lightmoor and Buildwas Junction – that stretch of the Wellington to Craven Arms railway had yet to be built.) By the time the OS map was surveyed, many of the wagonways had been and gone. To catalogue them all would be a substantial task, but it is worth outlining the routes of some of the more extensive.

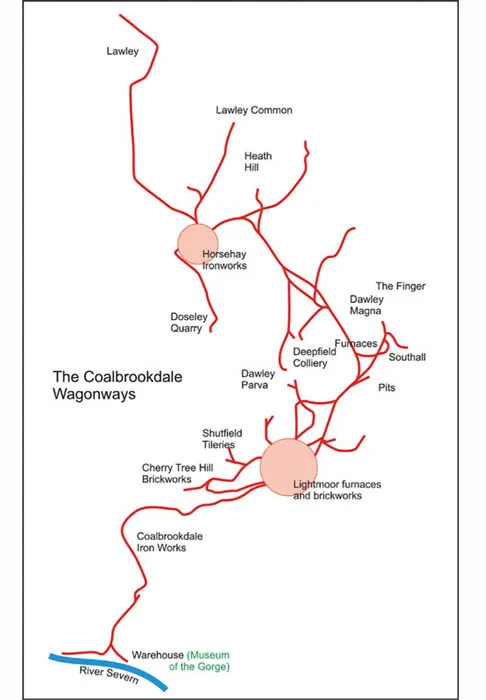

The Coalbrookdale wagonways were perhaps the most extensive and part of the network was still in use into the 1930s. The schematic (and simplified) map shows the lines running from the warehouse (now home to the Museum of the Gorge) and wharves on the Severn near Ironbridge, up Coalbrookdale (via Darby’s ironworks) to Lightmoor furnaces and brickworks, on via the furnaces at Dawley to Horsehay ironworks, to end at Lawley.

The Madeley Wood system linked Bedlam furnaces, beside the Severn near Ironbridge, with Blists Hill ironworks, the company’s mines and other operations. A high wrought iron bridge was built in 1872 to carry the line across the dingle from Blists Hill; a steep incline then took the line up past the All Nations Inn towards Madeley and the Meadow Pit Colliery. Beyond, the rails extended to Styches Colliery and back down to Bedlam, with a branch to brick and tile works above Ironbridge. The grade II listed Lee Dingle Bridge at Blists Hill remains a significant feature of the locality and the incline, now a public footpath, can be walked today.

Further north, early lines predated the railway developed by the Lilleshall Company and some remained for a number of years as feeders to their successor.

The wagonways developed over the years. Like modern railways, the earliest used flanged wheels, but wheels and rails were of wood. As iron-making and associated trades developed and iron became cheaper, wood was gradually replaced. The first iron wheels were used on the wagonway between Little Wenlock and Strethill in 1729. Cheaper to make, their disadvantage was that they wore the rails more quickly. Replaceable strips of hardwood – beech or plane and later iron – were fitted on the top surface of oak (and later softwood) rails. Track of this kind was known as ‘double way’ (not the same as ‘double track’). Typically, the sleepers and the primary rails were buried in the ballast, making a suitable surface for the horses – only the top rail would be visible.

In 1767, at Coalbrookdale, whole rails were cast for the first time; these were rapidly adopted as the new standard. South of the river, John Wilkinson was another early user of iron rails, again to replace wood on tramways in the Tarbach and Benthall areas. Cast deeper in the middle than at either end, the shape led to their description as ‘fishbelly’ rails.

A reversal of early railway practice came about with the development of the plateway, whose flanged or L-shaped rails enabled the use of plain wheels. First used in Shropshire on the Ketley Canal’s inclined plane, which was constructed in 1788, they came to the Coalbrookdale area around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Whilst the flange was generally on the inside, double-flanged or channel-shaped rails were used for crossings and similar – such rails can be seen today, in situ at the riverside warehouse in Ironbridge.

Iron could also be used for the sleepers of these plateways. They were cast with cut-outs for the rails, which could then be secured in place with wooden pegs. Rails were typically around 5ft–5ft 6in (1,500–1,700mm) in length, though the gauge used by the plateways could vary; 28in (710mm) was common and was in effect the wagonway ‘standard gauge’ within Coalbrookdale works.

Of the many plateways in eastern Shropshire, the Coalbrookdale network was possibly the most extensive. Parts of the route depicted are conjectural and it may have extended further north than shown.

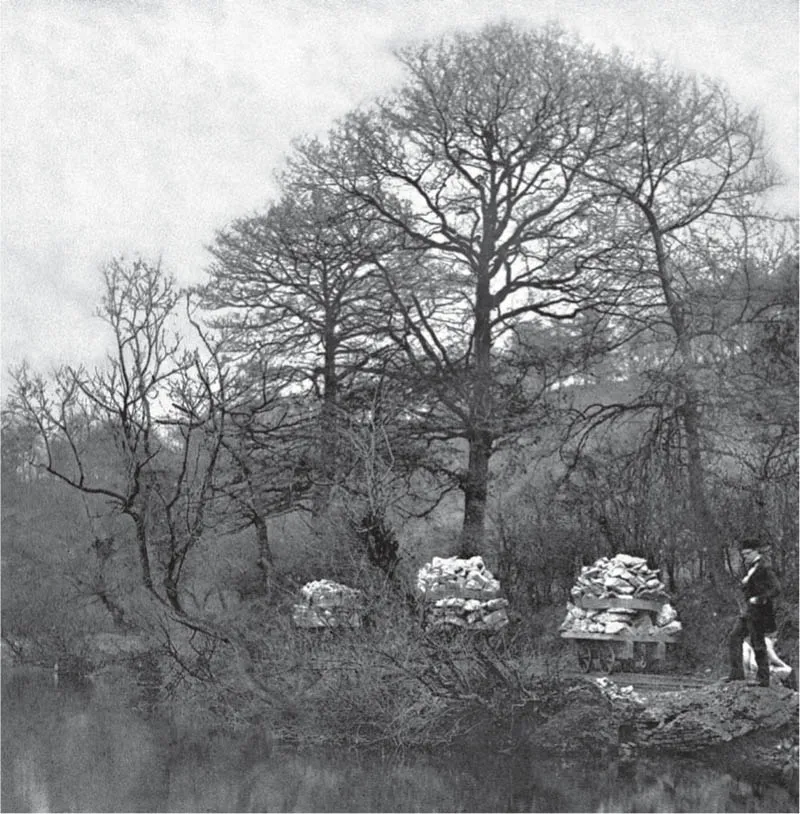

An early photograph showing a Shropshire ‘train’ – three wagons loaded with limestone stand on the plateway beside New Pool, Coalbrookdale. IRONBRIDGE GORGE MUSEUM TRUST

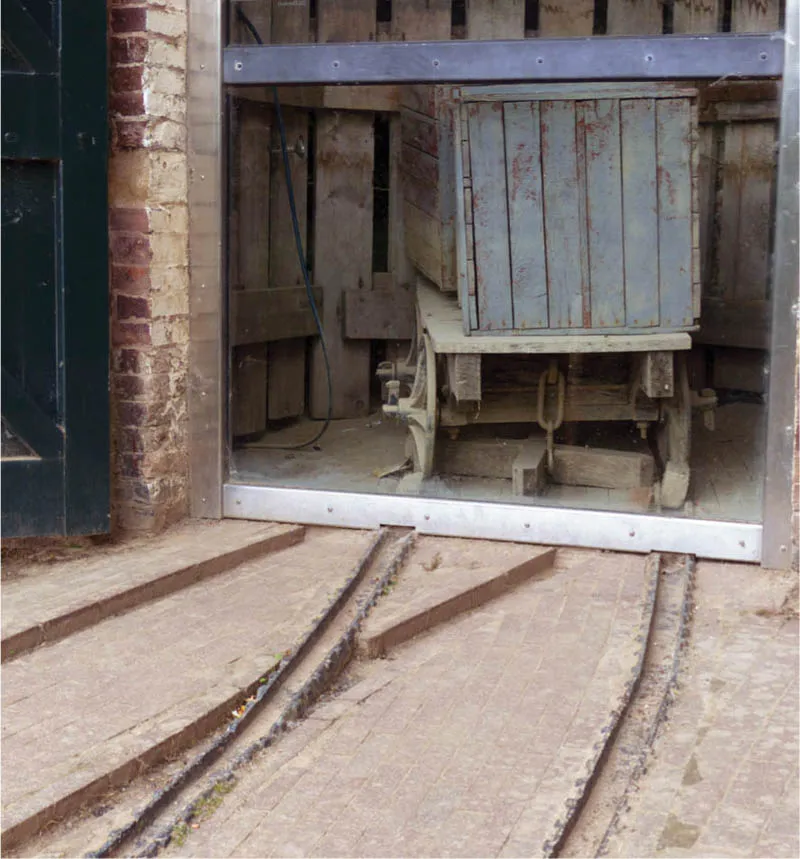

The Coalbrookdale plateway ran to the Severn near Ironbridge – its former warehouse is now the Museum of the River. A plateway wagon stands on the trough-type rails used where the L-shaped rail might cause problems. Photograph taken in June 2013.

North-West Shropshire

East Shropshire was not the only area to make use of early railways. On the western side of the county, where the border hills begin to rise, minerals have been exploited over a long period. Copper, lead, zinc and silver were extracted from Llanymynech Ogof, the mine on Llanymynech Hill, as long ago as the Bronze Age; the mine was last worked in the nineteenth century. More obvious to the casual visitor is the evidence of stone quarrying, again on Llanymynech Hill, and in the hills just to the north at Porthywaen, Blodwell, Whitehaven, Llynclys and Nantmawr. Despite their names, the quarries are, or were, mostly in Shropshire. The mine on Llanymynech Hill was in Wales (in the middle of what is now Llanymynech golf course), surrounded on three sides by Shropshire. Llanymynech itself neatly straddles the border – such is the nature of the border country.

In 1796, the Llanymynech branch of the Ellesmere Canal opened for traffic, tapping the output of the quarries and lime kilns. Means of transporting goods to the canal were now required. At Llanymynech, inclined planes and associated tramways were constructed from the ‘Welsh Quarry’ and the ‘English Quarry’ in 1806 and 1810 respectively, to lime kilns near the canal. A large Hoffman kiln was built here around 1900; nevertheless, quarrying and lime-burning ended in 1914. The kiln remains, within the care of Shropshire County Council, as part of the Llanymynech Heritage Area.

The narrow-gauge Crickheath Tramway opened in the 1820s, connecting Porthywaen quarries to a wharf on the canal. It closed in 1913, but traces remain, in particular the abutments of the bridge built to carry the tramway over the Cambrian Railways. These are on the site of the new Llynclys station opened by the Cambrian Railways Trust at the northern end of its short line to Pant and preservation of their remains seems assured. At Crickheath Wharf on the canal, the Waterway Recovery Group is restoring the tramway wharf area.

The Morda Tramway operated between 1813 and 1879, connecting Coed-y-Go Pit, near Morda, to Gronwen Wharf on the canal. When the Drill Colliery opened in 1836, it too was connected to the tramway and the tramway was upgraded for heavier loads. Later, railway engineer Thomas Savin constructed a narrow-gauge railway to connect Coed-y-Go to the Cambrian Railways near Whitehaven. Its life was short – it had gone by the time the tramway ceased operations.

In the extreme north-west of the county, the Quinta Tramway connected mines to the Shropshire Canal. For a short time, it also connected to the Glyn Valley Tramway. The latter, a roadside tramway, was for most of its life operated by steam tram engines, running from the (mostly) slate workings higher up the valley to Chirk station, on the Shrewsbury and Chester line, and ran entirely within Wales. However, when built, it connected not to the railway, but to the Shropshire Canal, and it did so within Shropshire.

Built around 1759, this bridge at Newdale carried the plateway between Horsehay and Ketley and is a rare survivor from those early days; 27 February 2013.

In this 1920s view looking towards the Severn warehouse (out of sight a little way along the road), are the disused remains of the ‘jinnie rails’ at Dale End, Coalbrookdale. The building on the left is in use today as a shop, but the buildings in the middle of the picture have long since gone. IRONBRIDGE GORGE MUSEUM TRUST

The End of an Era

The coming of the main-line railways marked the end of an era for the plateways, though perhaps not quite as rapidly as might be expected. The earliest wagonways had been constructed to provide links to the river; when the canals came, new plateways were developed as feeders. When the railways opened, pl...