![]()

Part 1

Synchronistic becomings

Philosopher Gilles Deleuze refers to immanence as a ‘plane of immanence’, a concept that he derives from Spinoza’s ‘substance’. The plane of immanence is composed of forces and intensities that can be understood as more-than-human forces that exist beyond human sensibility, and can be experienced only as felt affects. We can consider our body to be located anywhere within this plane, with immanence stretching infinitely in every direction as a common substance that transverses all bodies. I take the position that the plane of immanence is composed of autonomous affectivities, which, I will argue, with support of contemporary scholarship, are synonymous with both Jung’s archetypes and Spinoza’s essences. Autonomous affectivities can be conceptualized as moving freely across the plane of immanence, passing through the bodies that they encounter. As they pass through our human bodies their affects are creatively expressed (through dreams, awareness and/or phenomena), which can be intuitively apprehended as synchronistic becomings. I will argue that this is consistent with Jung’s position that archetypes can be known to us only as felt affects, and Spinoza’s (via Deleuze’s) idea that intuitive knowledge (or the third type of knowledge) is necessary for the mind’s apprehension of essences. Part 1 ends by arguing that conscious awareness of these autonomous affectivities is synonymous with experiences of synchronicity (via Jung), whereby body and mind resonate to creatively express the new. Archetypes and essences (qua autonomous affectivities) are non-representational and therefore difficult (if not impossible) to define. This is considered a strength in relation to this book, the aim of which is to reveal a pluralistic methodology for artistic research and creation. In Part 1 of this book, I aim to justify these ambitious claims with recent scholarship that connects the works of Spinoza, Deleuze, Guattari and Jung.

Dreamings

I have often wondered about possible links between the plane of immanence and the collective unconscious. But, given my status as artistic researcher and non-professional philosopher, I felt this type of investigation lay outside my research domain. However, while completing a course of Deleuze’s oeuvre with philosopher Jon Roffe, I admitted to him my secret interests. Rather than scorning me for my irrationality, he, instead, introduced me to the extraordinary scholarship of Christian Kerslake (2007), particularly his book Deleuze and the Unconscious, which explores the esoteric influences on Deleuze’s work. Thus began an exploration by which I discovered an undercurrent of scholarly interest exploring connections between Jung and Deleuze (and his work on Spinoza), including studies that consider the philosophy of Deleuze within spiritual frameworks (MacLure 2021; Ramey 2012). I add my voice, as an artistic outlier, to these fascinating studies, and with it hope to entwine this rich scholarship with sound studies, so as to provide a fresh perspective on the drivers of artistic action and the vital importance of intuitive processes in artistic experimentation and discovery. As has been articulated, the qualities of sound, which are transversal, vibratory and affective, lend themselves well to discussions of affect (Cox 2018; Goodman 2012) and, more broadly, to the ideas of more-than-human forces (Voegelin 2018; Schrimshaw 2017). Although the full range of possible sensory experiences will be considered in this book, sound remains the privileged medium, the reasons for which will become clearer in Parts 2 and 3.

I come to these ideas as someone who has long held a personal interest in Jung’s concepts of the collective unconscious and the archetypes (Jung [1954] 1968; [1961] 1989).1 I have always been a vivid dreamer, the adventures of which I continue to find inspiring, terrifying, baffling and enchanting (sometimes all at once), and, like many artists and creative thinkers, I find dreams to be a powerful source of personal transformation and creative possibility. The recent book Ludic Dreaming, which applies a variety of dream-like methods to speculate on the meaning of knowledge, is the only study I know of that has introduced dreams into sound studies. The authors write that ‘dreaming can . . . be understood as a method – the method – for thinking the multiplicity of the singular. If dreaming is anything at all, it’s that it always amounts to more than one thing’ (Cecchetto et al. 2017: 1). Across eight chapters the authors explore connections between sound, affect and dreams, expanding their method into a myriad of speculations. The reader is taken outside a world of certainties into unfolding explorations of the (un)known; just as dreams and sounds unfold unexpectedly, the book’s explorations creatively (and expertly) steer its readers across shifting terrains of dream-inspired studies. It is an important book insofar as it shows how the amorphous and mysterious phenomenon of sounds (and dreams) can inform newly idiosyncratic methodologies.

My intention here is not to present my research as a dream-inspired methodology, but, rather, to use theory and practice to explore relationships between archetypal affect and artistic practice. Rather than being driven by dreams, this book looks to the possibilities of the collective unconscious (considered here to be synonymous with Spinoza’s ‘substance’ and Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘plane of immanence’ – more on that later), particularly the creative possibilities that dwell therein. In particular, I want to mount an argument for Jung’s acausal principle of synchronicity as a method for the artist to subvert the controlling systems of signs that govern everyday life, by manifesting a-signifying events and experiences that rupture our normative associations. I consider this to be a political act that expands the possible experiences of the social body, and the individual artist. As Part 1 of this book unfolds, the reader should keep in mind that the driving force of this book is urban transformation via the intuitive processes of artistic experimentation. Guattari argued that we should pay attention to all three ecosophical registers – environmental, social and mental – in our struggle to diversify life. It is crucial, he tells us, that we should expand the expressive capacities of each ecosophical register in our struggle against the reductive/destructive forces of capitalist exploitation. Indeed, to begin to understand how we might intuitively apprehend autonomous affectivities in an everyday urban context (the topic of Part 3 of this book), we must first bring attention to those systems of signs that subsume our conscious life, thereby obscuring any lines of flight that might propel us into other possible worlds. And to understand this, we need to study Guattari.

Guattarian beginnings

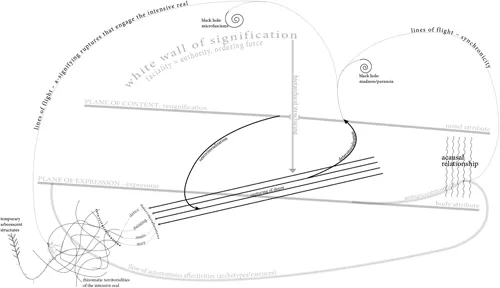

Although I have opened this chapter with a discussion of autonomous affectivities, the bulk of this chapter is focused on a diagram that I developed from a detailed reading of Guattari’s Lines of Flight: For Another World of Possibilities, his concept of ecosophy in The Three Ecologies and, to a lesser extent, Chaosmosis (I do not tackle Schizoanalytic Cartographies in this text). I owe a special debt to Guattari for his concept of the a-signifying rupture, which was the catalyst for my previous book that applied new ways of thinking about acoustic ecology practices in an urban context. As discussed in its Introduction, I proposed a sonic rupture model as an additional tool for acoustic ecologists, and soundscape designers in general, wanting to transform the noisy environments of city spaces. The book attempted to absorb Guattari’s ecosophical project – that mental and social ecologies are just as important as environmental ecologies – into acoustic ecology practices, via a broad application of affect theory. I expand these ideas in this book, by suggesting that the soundscape artist must have an understanding – even if only a rudimentary one – of Guattari’s insights into the dictatorship of the signifier and its capacity to determine relationships between humans and cities, thus grasping the deeper possibilities of Guattari’s activism. Using his thought, my diagram attempts to locate possibilities for artistic actions that aim towards ecosophical urban transformations. It is my intention to use the ‘lines of flight’ concept as I used the idea of the a-signifying rupture: to discover methods by which the artist might challenge the dictatorship of the signifier as encountered in the contemporary city, with the intention of opening new experiential worlds for humans. (This is not to devalue the non-human, but to be clear that the interventions proposed here are designed to cut across human consciousness.)

Two transversal therapeutic tools

In this section, I want to briefly describe a similarity between Guattari’s and Jung’s distinct psychotherapeutic practices, to explain why Jung’s archetypes appear in Figure 1 as an essential feature of my Guattarian diagram.2 The process of diagramming has a specific purpose for Guattari, which is directly connected to his broader schizoanalysis project. I am indebted to two Guattarian theorists for my understanding, to whom the reader should turn for a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between diagramming and schizoanalysis: Janell Watson (2011) and Gary Genosko (1996). In Guattari’s Diagrammatic Thought, Watson (11–13) provides a welcomingly clear description of diagramming, writing that Guattari’s ‘diagram produces and creates, bringing new entities into existence and thereby serving an ontological function. . . . In other words, diagrams do not represent thought; rather, they generate thought.’ Accordingly, the diagram I have produced (Figure 1) does not try to represent the concepts or ideas explored in Guattari’s book. Rather, it attempts to map key concepts into a diagram to generate new thought and action. Guattari’s diagrams have a strongly pragmatic dimension, in that they present openings for the possibility of action rather than merely representing systems and formulations that pre-determine action. As he writes, ‘pragmatic (symbolic and diagrammatic) transformations . . . each in their own way, overthrows the dominant system of redundancies [to] reorder . . . the vision of the world’ (2016, 162). These dominant systems of redundancies can be found in language, systems, institutions and so on, anything that, in its repeated infiltration into our lives, causes flows of desire to be captured into fixed (and thereby controlling) assemblages. The pragmatics of a schizoanalysis enables the rerouting of desire, via open and experimental practices, such that these fixed assemblages might be transformed. Hence a Guattarian diagram does not respond to but, rather, actively transforms power relations, particularly, as we will see, by subverting those semiotic structures that control perception. In keeping with Guattari’s project, my diagram too is intended to be pragmatic, to help generate new artistic thinking and creation in the context of the urban environment.

Figure 1 A diagram of artistic flights.

At the bottom of Figure 1 are two possible pathways for the activation of autonomous affectivities (also called archetypes and essences) – one that is directed towards the rhizomatic and another that is directed towards the ‘inner’ world of personal experience. It may appear odd that I add archetypes to a Guattarian diagram. I have certainly not come across any mention of archetypes by him (although there are some in Deleuze, as discussed later). However, this is perhaps less surprising when we consider that both the archetype and the diagram depend on the concept of the transversal, and this is the crucial link I wish to explore. In Guattari, the idea of the transversal is to be found in schizoanalysis, while in Jung it is integral to his archetypes and to his concept of the collective unconscious.

Guattari’s practice was informed by Jacques Lacan, who advanced Sigmund Freud’s understanding of the personal unconscious through a synthesis of linguistics and anthropology with unconscious processes. Guattari challenged Lacan’s methods by proposing a schizoanalysis, which, in its simplest formation, understands desire to be transversal rather than contained to isolated, individual bodies. The term ‘transversal’ has mathematical roots: it is a line that simultaneously crosses multiple points. As applied by Guattari, it describes desire occurring simultaneously across all bodies – not only humans, but all living and non-living bodies. As such, any form of ‘therapy’ is understood as relational and social, in that it deals with flows (and the rerouting) of desire across and between bodies. Gary Genosko (1996: 18) writes: ‘Schizoanalysis will avoid the pitfalls of personological and developmental psychologies . . . by establishing, on a case to case basis, “a map of the unconscious”. . . [T]his cartographer will not, like a psychoanalyst, close and reduce, but rather, open and produce. Such mapping opens onto experimentation.’ So, rather than desire being interpreted as a function of the patient’s own history of trauma, the patient is, instead, encouraged to explore their desire through experimental practices that connect them with other bodies. In keeping with this, the diagram I provide intends to offer a vital connection with other bodies (such as the reader) by encouraging, at the very least, a consideration of how the flows of desire with which we are connected are determined, or captured, by social and political systems. The diagram is not intended to provide answers or to represent a solution, but is, rather, offered as a tool to evoke creative and intellectual experimentation, discovery and flight.

In the case of Jung, his proposition that a collective unconscious exists beneath the personal unconscious (Jung [1954] 1968: 3) upset Freud, who located desire in the personal unconscious of each individual, which in his view was the proper focus of analysis. By encouraging us to encounter archetypes and the collective unconscious, Jung, instead, invites us to experiment with our own psyche as part of a process of self-transformation. In so doing, he created an approach to psychotherapy in which the patient drove their own process of transformation by submerging themselves in the deeper layers and mysteries of the collective unconscious, a process that can be described as bringing the personal and collective unconscious to consciousness (qua individuation).

It is interesting to note that it was the application of transversality, in the unconscious (Jung) and in desire (Guattari), that contributed to the break that both clinicians/thinkers had with their mentors/colleagues. By attending to the transversal, both challenged the all-powerful position of the therapist who uses transference (a process wherein the analysand (patient) transfers their power to the therapist) as a means to guide the individual patient through their traumas. Rather, the patient controls their own transformation in a shared (or collaborative) journey with the therapist. It is likely true that encounters with the collective unconscious, and the practice of schizoanalysis, are best supported and/or guided by therapists and clinicians; however, in both cases, power is retained by the patient. Thus, rather than power being transferred to the analyst who then directs the analytic process, the experimental/creative practice of the patient (both in and out of therapeutic sessions) becomes the driver of transformation.

To return to the issue of what connects Guattari and Jung: in the simplest sense, we might understand Guattari’s schizoanalysis as encouraging the patient to become aware of their interrelationship with transversal flows of desire, and Jung’s collective unconscious as enabling the patient to encounter and resolve challenges presented by the archetypes that reside in the transversal collective unconscious. With Guattari’s interests rooted in semiotic systems and the body as a nodal point for flows of desire, and Jung’s interests based in dream analysis and the symbology of the collective unconscious in relationship to the psyche, there is probably little else that connects these clinicians/thinkers. However, the claim that they both transversalized desire is a safe one, the effect of which was to empower the patient to discover their own pathways of development. But this is not a book of therapy! Rather, this simplified discussion is to point out that both Guattari and Jung were driven by their...