![]()

1 | THE BEGINNING

1842–77

“WE ARE ENTERING UPON AN EXPERIMENT not before attempted in this seat of learning—an experiment, which touches a variety of interests dear to the University, and dear to the legal profession of the State of Indiana” (McDonald 1843, 5). So began the inaugural address by Judge David McDonald, the first professor of law, on December 5, 1842, marking the birth of the Indiana University School of Law, the first public law school in the Midwest and the ninth-oldest law school in the nation. This event was the official beginning, but the idea for a law school at Indiana University had been conceived many years before.

Indiana University was founded in 1820 as the Indiana Seminary (Laws of Indiana, 1819, 82–83). In the earliest days, only Latin and Ancient Greek were taught. In 1828, the legislature changed the school’s name to Indiana College in order to better reflect its goals to teach youth “American, learned and foreign languages, the useful arts, sciences, and literature” (Laws of Indiana, 1827, 115–19). In 1838, the Indiana legislature once again changed its name, this time to Indiana University, stating that the school’s mission was for the education of youth in the “American, learned and foreign languages, the useful arts, sciences (including law and medicine) and literature” (Laws of Indiana, 1837, 294–98). This was the first mention of the study of law as part of the mission of the university.

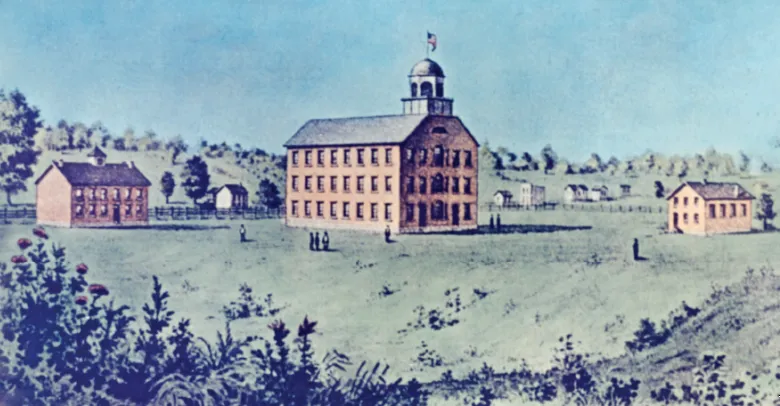

FIG. 1.1. Seminary Square campus as it looked at time of founding of the law department. Left to right: Seminary Building (circa 1825), First College Building (1836), and Laboratory (1840). Artist: William B. Burford. Circa 1850. IU Archives P0022535.

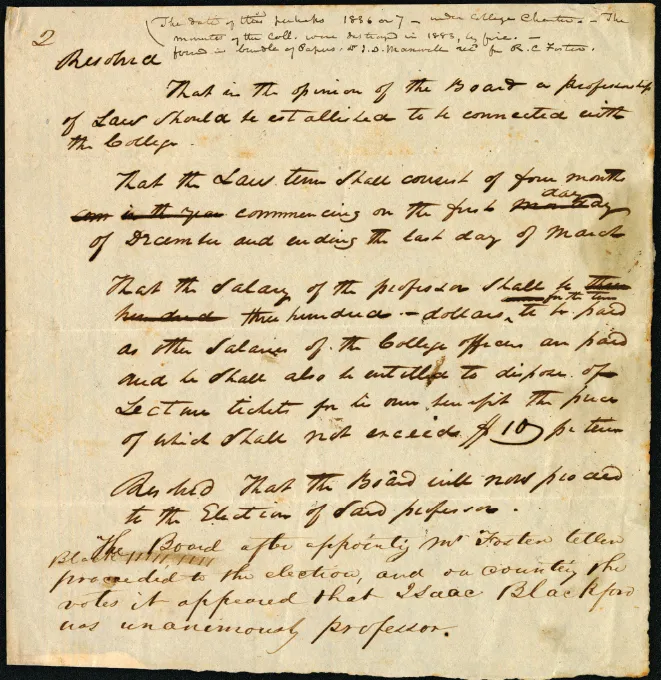

FIG. 1.2. Piece of paper that escaped the fire of 1883, the only evidence that trustees approved the establishment of a law professorship in 1835. Document is dated September 31, 1835 (assume it was actually September 30, 1835). IU Archives.

Although most official university records were destroyed in the fire of 1883, a piece of paper containing a resolution by the trustees from the year 1835 establishing a professorship of law survived, apparently having never been placed with the official records. A notation on the resolution indicated that Judge Isaac Blackford, a member of the board of trustees, was elected to the position, but he declined for unknown reasons. Three years later, after the legislature added the study of law to the university’s mission, the position was offered to Judge Miles G. Eggleston, who also declined for unspecified reasons. No other formal offers were extended until 1841, when the trustees offered the position to General Tilghman A. Howard.

According to the minutes of the board of trustees for July 1841, the trustees sent a letter to Howard in which they expressed the desire for “the building up of a Law school that shall be inferior to none west of the mountains. We aim at the establishment of a Law school that shall not only increase the Legal knowledge but elevate the moral & intellectual character of the Profession throughout Indiana.” The letter went on to say, “In a word we wish the Law Students of Indiana University to be so trained, that they shall never, in the attorney forget the scholar and the gentleman.” Howard was offered the fees paid by the law students as well as $400 the first year and $300 annually after that. The trustees anticipated the enrollment of fifteen to twenty students the first year. As an added incentive, the trustees declared that the law professor would be independent, answerable directly to the board.

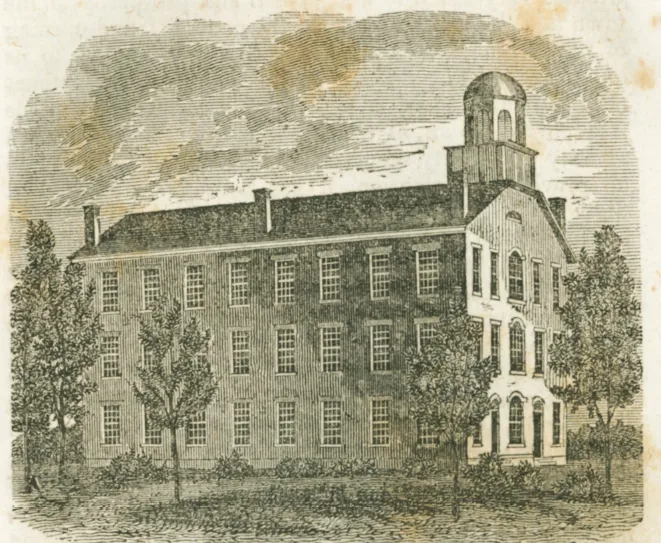

FIG. 1.3. First College Building, site of the inaugural lecture given by David McDonald on December 5, 1842, in the chapel. Law classes were held in this building until it was destroyed by fire in 1854. IU Archives P0022519.

Although Howard was flattered by the offer, he declined, indicating that it would require him to make too many sacrifices. Finally, in June 1842, the board of trustees secured the appointment of Judge David McDonald as the first professor of law, at a salary of $1,000 per year, and all fees paid by law students would go to the university. The trustees were pleased to finally see the law department come to fruition, believing that it would add greatly to the standing of the university.

After years of attempts, the law department was officially launched with the lecture given by McDonald on December 5, 1842. As was the custom, the lecture was open to the public and held in the university’s chapel. There is no record indicating how many new law students attended this lecture, but two years later, five students graduated in the department’s first class. McDonald ended his address with a challenge to the new students of law: “And now, young gentlemen, if you are willing to endure the labor of mastering this noble science; if you are willing to spurn the trifles which engage the time and affections of too many of our youth; if you glow with honorable emulation; if you desire to be distinguished among your fellow citizens, and useful to our beloved country,—here is a field worthy of our labor—a field, in which you may, at once, gratify a laudable ambition, and promote the best interests of society” (McDonald 1843, 22).

Law department applicants were not required to have a high school diploma, the university requirement for admission, but instead needed to produce satisfactory testimonials of good moral character. The trustees originally envisioned that students would complete two years of study with two terms in each year, although it was possible to enter as a senior if the student had made sufficient progress in the study of law elsewhere. The terms were intended to consist of four months each, but the trustees reluctantly agreed, at least temporarily, to reduce the requirement to a single three-month term each year, beginning on the first Monday of December. McDonald suggested this change in order to encourage student enrollment and to accommodate his schedule riding the circuit, which began the first Monday of March and ended on the last day of November. It was understood that if the legislature allowed a change in his court schedule, the term would be increased to four months, beginning on the first Monday of November. With this change, the trustees reduced his salary to $100 per month during time that classes were in session.

Instruction consisted of lectures on various branches of the common law and equity jurisprudence, examinations, and moot courts, which were held every Saturday. There students were given exercises in pleading and arguing legal questions, and the judge also gave an opinion on the questions of law involved in the exercise. Textbooks used were listed in the Catalogue for 1845 as Blackstone’s Commentaries, Story’s Commentaries on the Constitution, Chitty on Contracts, Stephen on Pleading, Kent’s Commentaries, Chitty on Bills, Chitty on Pleading, Greenleaf’s Evidence, and Mitford’s Equity Pleading.

Though there is no existing record of how many students attended the first lecture, in 1843 there were fifteen law students: six seniors and nine juniors. The first graduating class in 1844 consisted of five men: Francis Patrick Bradley, who practiced in Washington, Indiana; Joseph Blair Carnahan, who practiced in southern Indiana; John M. Clark, who practiced in Vincennes, Indiana; Jonathan K. Kenny, who practiced in Terre Haute, Indiana; and Clarendon Davisson, who practiced in Petersburg, Indiana, in addition to being a newspaper editor in Bloomington, Indianapolis, Chicago, and Louisville and appointed consul in Bourdeaux, France (Wylie 1890, 310). By 1847, the department was successful enough to add a second professor, Judge William T. Otto. According to the 1847 Catalogue, its success “exceeded the expectations of its friends” (15).

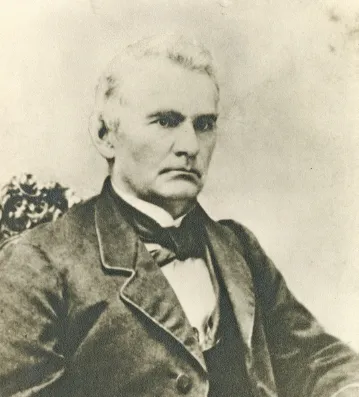

FIG SIDEBAR 1.1. Judge David McDonald, first law professor, 1842–53. IU Archives P0079349.

JUDGE DAVID McDONALD

David McDonald was born in Millersburg, Kentucky, in 1803 and moved to Indiana when he was fourteen years old. He was a school teacher in Washington, Indiana, when he met a lawyer who encouraged him to study law. McDonald read the law, was licensed to practice in 1830, entered private practice in Washington, and was also a member of the Indiana General Assembly from 1833 to 1834. In 1838, he was elected judge of the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Indiana and served in that capacity for fourteen years.

McDonald became the first professor of law at Indiana University in 1842, serving in that role until 1853, when he resigned to return to private practice in Indianapolis. Upon his resignation, the university presented him with an honorary LLD degree. In 1856, he published McDonald’s Treatise, a book designed for justices of the peace and constables, which was reprinted many times. On December 12, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln nominated him to a seat on the US District Court for Indiana. McDonald was confirmed by the US Senate on December 13, 1864, and received his commission the same day, serving until his death on August 25, 1869, in Indianapolis. He is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

LIFE IN BLOOMINGTON IN THE 1800s

The following is an excerpt from a letter published in the Alumnus, written by William Pitt Murray (LLB; 1849), describing travel to Bloomington, the town, and the law department in 1848 (Murray, “The University Fifty Years Ago,” Alumnus, February 1899, 6–10).

Dear Sir:

Bloomington, fifty years ago, was a country village of the Hoosier type, without side-walks or graded streets,—mud, mud everywhere. Its home and business houses were of the most primitive kind—the old State University building, built without regard either to ancient or modern architecture or convenience. The village was off the high-ways and lines of travel—even more inaccessible than New York or San Francisco, if you desired to travel pleasantly.

I remember but as yesterday the bleak, chilly Thursday afternoon in November on which I left my home in Centerville, Ind., for Bloomington, taking my seat in a stage coach. This was then the only means of public travel. There was but one railroad in the State of Indiana, that from Madison to Indianapolis. It is sixty-two miles from Centerville to Indianapolis, yet it was not until nearly noon on Saturday that we were driven up to a small hotel in Indianapolis … and were then told that we would have to remain in Indianapolis until Monday morning, as no stage went out to Bloomington until then. About four o-clock Monday morning a rapping at the door awoke me, when I was told that the stage (that is, if a three-seated open wagon, drawn by two Hoosier ponies could be called a stage) for Bloomington was at the door…. It not only rained but poured that day,—mud and slush everywhere. We were compelled to walk every now and then to assist the ponies. At a log building, a way-side inn, we had breakfast, and near midnight we drove up to Orchards’ Hotel, in the college town…. The next day [Robert H.] Milroy and myself, who had arranged to room together, commenced looking around for winter quarters…. we secured board with the Misses Henderson not far from the college building, where we had a good clean room; good feather beds;… wood furnished in sled lengths, which we had to cut into fire-wood lengths, and carry up to our room,—and all of this for one dollar and twenty-five cents a week….

Society in Bloomington fifty years ago was, no doubt, different from now. Some of the young men wore jeans suits and cow-hide boots. The amusements were not as numerous as now, perhaps—mostly confined to church sociable, and now and then some tramp would come along and deliver a lecture of Phrenology or some kindred subject. The Judge, every two or three weeks, would, at the close of his Friday lecture say, “Young Gentlemen, I will be at home tomorrow evening.” We knew what this meant—a dozen or more village girls would be there. We had fun as a matter-of-course and sometimes turned the house upside down, but it was all right: the Judge never appeared to see what was going on. Some two or three of the young men got caught, and the population of Bloomington was reduced to that extent….

Very respectfully yours,

WILLIAM PITT MURRAY

The law department was successful, but the university had constant financial difficulties. At their October 1846 meeting, the trustees considered closing the department due to insufficient funds. Instead they sent a communication to McDonald asking if he would consider continuing to teach with only the fees paid by law students, as well as a room and firewood, as his sole compensation. Although unhappy with this proposition, McDonald agreed to continue for the time being without his salary.

Financial problems were not the only obstacle to the law department’s success. Indiana approved a new state constitution in 1851, which included Article VII, Section 21, stating “every person of good moral character, being a voter, shall be entitled to admission to practice law in all Courts of justice.” This was likely included to placate Jacksonians, who were concerned that educational requirements would lead to lawyers becoming the ruling clas...