![]()

Part 1: Initial Public Offering (IPO) – a theoretical perspective

The first part of this book provides a theoretical framework for the IPO-related concepts addressed during an IPO project.

Chapter 1 outlines the basic corporate finance concepts necessary to understand the significance of an IPO for raising equity capital in financial markets. These include the different financing types and sources: equity vs. debt, internal vs. external. Organizational and conceptual differences between investment and commercial banking are addressed, as well. Moreover, past and current developments in IPO markets are described and put into a practical perspective.

Chapter 2 takes a closer look at investment banking’s internal processes and explains investment banks’ role during an IPO including the individual tasks performed by them. Thus, this chapter addresses the main tasks carried out by investment banks before, during and after an IPO.

Finally, Chapter 3 approaches the difficult task of finding a value for an IPO candidate company from a theoretical perspective. As will be seen, value can differ substantially according to the valuation method used. And there is not one single “correct” valuation method, leaving a lot of room for discussions and arguments in an actual IPO process.

1 Corporate Finance – an overview

1.1 Equity versus debt

This chapter provides a brief outlook on the most common financing means used by companies: equity and debt. It explains the reasons why companies need funding and what financing options companies can choose from. A brief description of the main players in the funding arena will be provided and a brief summary of the current IPO market intends to give a real-life perspective on the theoretical approach.

1.1.1 Why capital is needed

According to widespread economic understanding, only those companies which provide products or services in demand are successful on the long run. Therefore, companies need (innovative) products or services that satisfy customer needs in order to be able to survive in the market. The research and development as well as the production process for these goods and services require resources (also known as “assets”). These assets can either be of tangible (i.e. physical) or intangible nature ranging from machines and buildings to more specific forms like patents. They are acquired through financial activities, commonly referred to as “investments”. However, no predetermined financing formula exists as it is common practice to use a trial-and-error process to determine the company and sector specific investment practice. For example, the pharmaceutical industry is known for long testing procedures and approval processes for the national health agencies (e.g. Federal Drug Administration - USA, European Medicines Agency - Europe) whereas other companies’ main capital need rests on the establishment of production facilities or (international) distribution channels.

1.1.2 Types of capital

Generally, companies have two major financing options: equity or debt.

Equity in accounting terms presents the residual value (i.e. the difference) between assets and liabilities. From a more company-related approach equity describes its monetary “value” for the owner(s) and their claim on future profits of the company. The different concepts of value and price will be discussed in chapter 3. In this sense, the claim on a prospective profit distribution is sliced into a certain number of pieces that can be traded publicly (called stocks or shares). An IPO is an equity financing method as shares (and therefore equity instruments) are offered for the first time to the investing public. Equity investors are usually compensated for their engagement through dividend payments and/ or through an increase in stock value.

Debt capital is based on a contractual relationship between an investor (“creditor”/lender”) and a “debtor” or “borrower” which lacks funding. The debtor compensates the lender for not being able to use the capital himself by paying a certain interest rate on the borrowed capital. In economics, this concept is known as “opportunity cost”. In the personal realm, debt comes in the form of credit card debt or mortgage loans (special type of loan used to finance real estate). However, corporations also approach financial markets in order to issue corporate debt obligations (“corporate bonds”). The respective interest rate is determined by the pre-determined periodic coupon payments and the face value which will be returned at maturity.

There are also funding instruments in the form of a mixture between debt and equity. They are commonly known as “mezzanine” or “hybrid” capital. Depending on the prevalent characteristics, they are clustered into debt-like and equity-like mezzanine instruments. Mezzanine debt instruments often include options, warrants or other rights. Convertible bonds are a typical example for mezzanine instruments.1 They pay a fixed coupon and promise the payback of the face value, while giving the investor the choice to exchange the bonds into shares.

1.1.3 Characteristics of debt and equity capital

Debt and equity financing differ substantially. An IPO is considered to be equity financing since it is the first time that a company offers its shares to the public. This paragraph discusses the main differences between debt and equity funding for both, the investors and the issuing company.

With the purchase of equity instruments (e.g. shares of a company) an investor becomes a partial owner of a company. Therefore, depending on the equity form the shareholder is at least liable with the entire capital invested. In case of a non-public (i.e. private) company with unlimited liability an owner commits also all personal wealth in case of filing for bankruptcy.2 In contrast, debt financing involves no liability and the maximum loss can only amount to the lent capital.

Shareholders, thus partial owners of the company (i.e. equity investors) have also claims on the company’s profits (and liabilities in case of losses). Therefore, there is no pre-determined compensation ceiling or floor limiting compensation. Debt is compensated by a fixed interest rate or quasi-fixed interest rate, known as “floating interest rate” (the reference points depend on the specific debt financing instruments e.g. mortgage loans are usually LIBOR or EURIBOR based). Hence, no claims on profits exist for debt instruments. However, in contrast to equity, the pre-determined conditions specified in the contract (“loan agreement”) limit the claims on debtors.

In case of a bankruptcy, shareholders can only make a claim on the residual (i.e. remaining) assets after all other third-party liabilities have been compensated. Debtors hold a superior position as their claims are served before those of the shareholders and therefore often retrieve at least part of their invested money. Usually, there is a certain hierarchy when serving debtors according to the issuing date and certain clauses in the issuance contract. Therefore, debt securities are classified as senior and junior-ranked securities.

To a partial owner, equity instruments give (at least theoretically) the right to administrate the company. Therefore, public companies hold annual shareholder meetings, chaired by the company’s management board, where each shareholder can exercise his voting rights. As debtors have only a contractual relationship with the company, no direct involvement in corporate matters is sought.

Another differentiating factor relates to time. Equity financing is unlimited as ownership does not terminate at a certain point in time. Clearly, that relationship ends with the sale of the shares or bankruptcy of the company. The debt agreement forms the legal basis of a debt instrument and specifies special features. In its purest form, it spells out a framework with the most basic conditions including the repayment schedule, time horizon, interest rate and calculation form (e.g. annuity, bullet loan, etc.).

The tax treatment of debt and equity differs, as well: Whereas payouts for equity instruments (i.e. dividends) are subject to taxation (the precise rates vary by national jurisdiction), interest payments are tax deductible for the company.

1.2 Where the money comes from

1.2.1 Internal and external financing and sources of capital

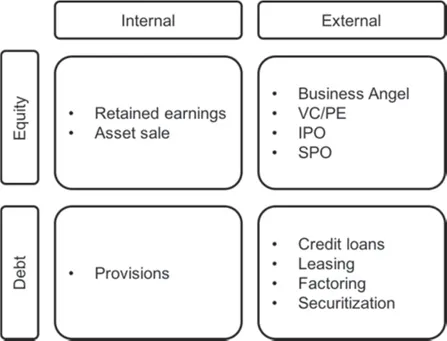

In the previous chapter, financial instruments were grouped according to legal differences (equity and debt). Another criterion how funding opportunities can be clustered is the origin of the capital: A company can finance its investment activities internally or it can approach external (third) parties for financing. Therefore, the entirety of financing options open to companies follows a 2x2 matrix which is presented below.

Exhibit 1: Illustration of the main financing options

Source: Own presentation

In “internal” financing, no capital flows from external third parties to the company, and funding is therefore generated by the company’s activities itself. The most intuitive form is the sale of assets at a profit (e.g. sale of produced goods, buildings or company cars etc.). Other more sophisticated forms include reserves. Reserves can be hidden (not reflecting the asset’s value on the balance sheet) and detectable according to some Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (e.g. German GAAP – HGB and to a lesser extent IFRS). Even though IFRS is based on a “fair value” approach meaning that balance sheet positions are recorded at market values, there exist a myriad of balance sheet positions where hidden reserves are possible.

The most prominent example for observable reserves are retained earnings which result from previous years’ profits that have not been distributed to shareholders.

Provisions are another form of self-financing (debt in this case). Provisions are booked when a given periods business activities can be expected to cause a future cash outflow with the exact timing and/ or the amount of the outflow unknown.

As noted before, companies generally cannot finance their entire investment activities through internal sources. Therefore, third parties providing capital are needed. External financing refers to the fact that money flows from external parties to the company. Main players in a company’s early life include private investors such as family and friends, business angels or high net worth individuals. “Family and friends” financing is often used for start-up companies that have no access to more sophisticated forms of finance or bank loans (due to the high risk associated with the repayment or the lack of collateral). Often, Business Angels are former start-up founders who have turned into wealthy individuals.3 They acquire stakes of companies and often take on an advising role in a specific sector (usually based on experience and interest). High net worth individuals tend to manage their investments through so-called “family-offices”, in which sometimes an entire family-clan is represented.

A...