![]()

CHAPTER 1

Astronomy and Cosmology: A Scientific View of the Universe

SINCE ANCIENT TIMES, humans have tried to make sense of the universe by observing objects beyond our world – the sun, moon, stars and planets. Babylonian and Egyptian civilizations, realizing that astronomical events are repeated and have cycles, charted star positions and predicted celestial events such as eclipses, comets and the motions of the moon and the brightest stars. Their records formed the basis for timekeeping and navigation.

Adopting centuries of observations before them, the ancient Greeks named groups of stars, or constellations, after mythological figures like Orion, the hunter, and Gemini, the twins Castor and Pollux. The forty-eight Western constellations listed by Ptolemy in the first century are among the eighty-eight constellations used to navigate the night skies today. Likewise, the Romans gave us the names for some of our planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Reflecting the sun, these were seen as bright ‘stars’ in the sky.

The invention of the optical telescope in the seventeenth century changed forever the idea of an earth-centred universe. It was soon clear that the universe was much larger than ever imagined. Searching deeper into space, astronomers found more planets of our solar system (Uranus and Neptune), minor planets or asteroids, satellites (moons), dwarf planets (like Pluto), gas clouds, cosmic dust and whole new galaxies.

Today’s astronomical instruments include satellite-borne telescopes that detect radiation from faraway cosmic objects, and space probes that can bring back information from other planets. Armed with these tools, astronomers are discovering more about the particles and forces that make up the universe, the processes by which stars, planets and galaxies evolve, and how the universe began. They have also discovered a large part of the universe that cannot be seen with any type of telescope. This ‘dark matter’ is proving to be one of astronomy’s greatest mysteries.

Early Star Catalogues: Gan De

Chinese astronomer Gan De (c. 400 to c. 340 BCE) and his contemporary Shi Shen are believed to be the first named astronomers in history to compile a list of stars, or star catalogue. Gan De lived during the turbulent Warring States period of ancient China, when the regular twelve-year passage across the skies of the bright, visible light of Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, was used to count years, so it was the focus of concentrated observations and predictions. Without telescopes, Gan De and his colleagues had to rely on the naked eye, but they made acute calculations to guide them as to the best times to make celestial observations.

In the night sky above mainland China, Gan De saw and catalogued more than a thousand stars, and he recognized at least a hundred Chinese constellations. His star catalogue was more comprehensive than the first-known Western star catalogue, drawn up 200 years later by the Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who listed about 800 stars.

Gan De’s observation of what was almost certainly one of Jupiter’s four large moons was the first-known record in the world of seeing a satellite of Jupiter – long before Galileo Galilei officially ‘discovered’ the satellites in 1610 using his newly developed telescope.

Shi Shen and Gan De were among the first astronomers to approach an accurate measurement of a year, at 365¼ days. In 46 BCE the Greek astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria would be employed by Julius Caesar to realign the Roman calendar to this more accurate measurement. The resulting Julian calendar remained in use across Europe and Northern Africa until 1582 and the introduction of the Gregorian calendar that is still in operation today.

Geocentric View of the Cosmos: Aristotle

In the fourth century BCE, while the ancient Chinese states battled for supremacy, classical Greek culture was spreading to numerous colonies around the eastern Mediterranean, laying the foundation stone that would underpin Western thought into the modern era.

The Greeks felt they were at the centre of the cosmos, and the night skies added to their belief. Stars appeared to rise and then set, as if on a journey around the earth. (The illusion is a result of the earth spinning on its axis: stars appear to move westwards across the sky simply because the earth rotates eastwards.)

They identified ‘wandering stars’, whose positions move in relation to the ‘fixed stars’ that twinkle in the background. The wanderers were the sun and moon and five then-known planets of our solar system: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. The Greeks concluded that the cosmos, or universe, consisted of the earth, a perfect sphere (not flat as archaic cultures had thought) that was stationary at the centre of everything, with heavenly bodies – the sun and visible planets – orbiting in uniform motions and perfect circles around the earth. The ‘fixed stars’ were located in the outer celestial sphere – astronomers didn’t notice the actual movements of these faraway stars until the nineteenth century.

To this ‘geocentric theory’ the great natural philosopher and scientist Aristotle added his own ideas. The earth and heavens, he theorized, were made up of five elements: four earthly elements (earth, air, fire and water) and a fifth element, a material filling the heavens and arranged in concentric shells around the earth, called aether. Each concentric shell of aether contained one of the heavenly bodies, orbiting around the earth at a uniform pace and in a perfect circle. In the outermost shell the stars were all fixed. The earthly elements came into being, decayed and died, but the heavens were perfect and unchanging.

Aristotle’s cosmological ideas were accepted in the Arab world and reintroduced into Christian Europe during the Middle Ages.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

Aristotle was a giant of the classical Greek intellectual world and his ideas had a lasting influence in the West. Born to a Macedonian medical family, he was one of the stars of Plato’s school in Athens.

He left Athens possibly because he was not appointed head of the Academy after Plato’s death, and perhaps also because Philip of Macedon’s expansionist wars had made Macedonians unpopular. But he returned to the city in 335/34 BCE after Alexander the Great – Philip’s son and Aristotle’s pupil – had conquered all of Greece.

While running his own school in Athens, the Lyceum, Aristotle continued extensive studies into almost every subject then defined. His method of teaching and debate was to walk around discussing topics, which is why Aristotelians are often called Peripatetics.

Following Alexander’s death, ill feeling towards Macedonians flared up again and Aristotle fled, supposedly stating in a reference to the execution of the philosopher Socrates seventy years earlier: ‘I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy.’

Precession of the Equinoxes: Hipparchus

Classical Greek culture flowed eastwards in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests, inspiring scholars like Hipparchus (c. 190 to c. 120 BCE) of Nicaea (in what is now Turkey).

While compiling a star catalogue, Hipparchus noticed that the positions of stars did not match earlier records: there was an unexpected systematic shift. He concluded that the earth itself had moved, rather than the stars. He had detected the earth’s ‘wobble’ as it rotates around its axis – imagine the slow wobble of a spinning top, with its axis tracing a circular path. One such circuit caused by the earth’s wobble takes about 26,000 years – a figure calculated very accurately by Hipparchus.

He named the wobble the precession of the equinoxes because it causes the equinoxes (the two dates each year, in March and September, when day and night are of equal length) to occur slightly earlier than expected with reference to the ‘fixed stars’.

Over time this discrepancy caused the seasons to occur at different times in the ancient calendar systems. These were based on the solar measurement for a year (the ‘sidereal year’), which is the time it takes for the sun to revolve from a position in the sky marked by a fixed star to the same position again, as viewed from the earth (or, as we now know, the time it takes for the earth to orbit once around the sun). Hipparchus solved the problem by inventing a new measurement for a year, the ‘tropical year’, or the time it takes for the sun’s apparent revolution from an equinox to the same equinox again. About twenty minutes shorter than the sidereal year, the tropical year is the basis for our modern Gregorian calendar. It ensures that the seasons occur in the same calendar months each year.

Hipparchus used Babylonian data to calculate the lengths of the sidereal and tropical years with great accuracy: indeed, far more accurately than Ptolemy, who came about 250 years later, showing just how far Hipparchus was ahead of his time.

A Mathematical Cosmos: Ptolemy

Ptolemy, born towards the end of the first century, and the last of the great ancient Greek astronomers, also adopted the geocentric view of the earth at the centre of the cosmos. His contribution was to create the first model of the universe that would explain and predict the movements of the sun and planets in mathematical terms. His model appeared to answer a question that had puzzled the Greeks for some 1,400 years: why, if a planet was orbiting around the earth at the centre of the universe, did it sometimes appear to move backwards with respect to the positions of the ‘fixed stars’ behind it?

Despite Ptolemy’s fundamental beliefs, in order to explain mathematically the movements of heavenly bodies he had to violate his own rules by assuming that the earth was not at the exact centre of the planetary orbits. Pragmatically, he and his followers accepted this displacement, known as the ‘eccentric’, as just a minor blip in the essential geocentric theory.

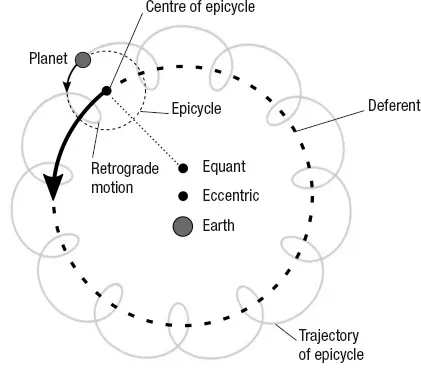

Ptolemy used a combination of three geometric constructs. The first, the eccentric, was not new, nor was his second construct, the epicycle. This proposed that planets do not simply orbit the earth in large circles, but instead move around small circles, or epicycles, which in turn revolve around the circumference of a larger circle (the deferent) focused (eccentrically) on the earth. Progress along the epicycle explained why planets sometimes appear to move backwards, or in ‘retrograde motion’ (see diagram, here).

His third construction – the equant – was revolutionary, and Ptolemy invented it to explain why the planets sometimes seemed to move faster or slower, rather than uniformly, as viewed from earth. He suggested that the epicycle’s centre of motion on the circumference of its larger circle (the deferent) is not aligned with either the earth or the eccentric centre of this larger circle, but with a third point, the equant, which is situated opposite the earth and at the same distance from the centre of the larger circle as is the earth. It is only from the point of view of the equant that the planet appears to be in uniform motion.

These three mathematical constructions – epicycle, eccentric and equant – were complex and unsatisfactory to purists, but they seemed to explain some puzzling aspects of astronomy, such as the retrograde motion of planets and why planets appear brighter, and therefore closer to earth, at different times. Together they allowed predictions of planetary positions that approximated those of a modern heliocentric view of the universe, in which the planets orbit the sun in elliptical paths.

Ptolemy’s geocentric model was first followed in the Middle East and then in Western Europe. It aligned with religious belief, and scholars who dared dispute it faced a death sentence from the rigid and repressive Catholic Church. But by 1008, Arab astronomers w...