![]()

![]()

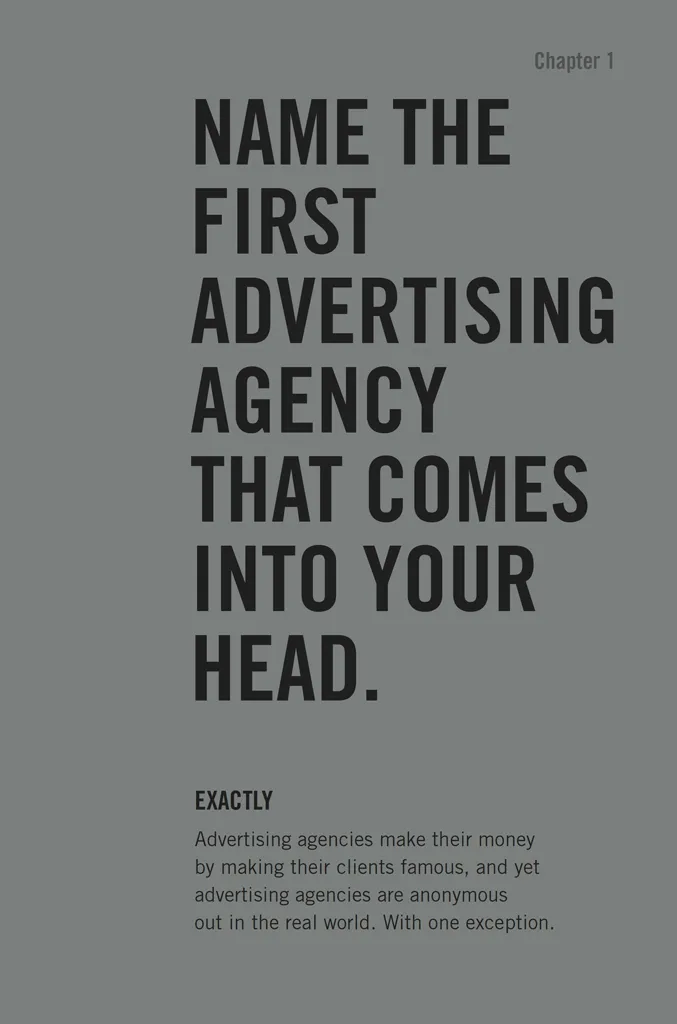

IN 1989, THE OUTDOOR ADVERTISING COMPANY, Maiden, launched a competition inviting agencies to submit ideas to promote themselves on a big Spectacolor screen in Piccadilly Circus, London’s neon light centre. Saatchi & Saatchi’s entry, created by copywriter Adam Keen and art director Antony Easton, came in two parts. The first half of the message read ‘NAME THE FIRST ADVERTISING AGENCY THAT COMES INTO YOUR HEAD’, which was followed, after a brief blank screen, with ‘EXACTLY’.

But how did Saatchi & Saatchi’s unique fame come about? It was almost certainly driven at least by the recognition that fame is priceless and in turn fame begets fortunes. Of course, it’s one thing to recognize the value of something like fame, but it’s quite another to make sure you get more than your fair share of it.

How, for a start, do you make your company interesting enough for it to be constantly written and talked about? How do you step out from the shadows cast by your clients? The good news is you don’t necessarily have to turn yourself into a media tart, attending as many high-profile events as possible and providing gossip columns with their lifeblood. In fact, in Saatchi & Saatchi’s case, the very opposite – being reclusive – paid huge fame dividends.

For Charles Saatchi, being reclusive meant not appearing in public unless it was absolutely necessary. He may not be Howard Hughes but he has gone to great, and occasionally bizarre lengths to avoid meeting people – clients in particular. Many people tell the following story, but Ron Leagas, who would later become managing director of Saatchi & Saatchi before leaving to start up his own agency, saw the action first-hand. It revolves around a significant new business pitch for Singer Sewing Machines:

‘I recall starting the pitch around lunchtime in the basement meeting room [of Saatchi & Saatchi’s original Golden Square offices] and, true to form, found myself distracted from my earnest pitch by the sight of Charlie watching the meeting from the adjacent room through the tiny film projector window. The pitch was going well but it went on and on with Brian Goshawk [marketing director] and Gill Lewis [marketing manager] quizzing and probing us mercilessly. We finally ascended the spiral staircase to see them off at around 7 p.m. By this time, Charlie had deserted his spy post and found himself exposed on the ground floor as the only person there. Fearing he would have to be introduced to this important prospect, he pretended to be a cleaner, screwing up an ad layout and using it as a cleaning cloth.’

It’s a moot point whether Charles’s reclusiveness sprang from his shyness or from his strategic nous, because Charles was certainly no shrinking violet when it came to dealing with the press. He was an expert at publicity management and his sense of how to control information was acute.

John Tylee, a former associate editor of the advertising industry magazine Campaign, recalls Charles’s way of working with the media (or should that be working the media?): ‘Having close links with the trade press was, of course, essential and the agency was adept at cultivating those links. Nobody was better at it than Charles, who kept Campaign supplied with a constant stream of news tips. So many, in fact, that when he announced the formation of Saatchi & Saatchi in September 1970, the magazine splashed with the story. In the light of subsequent events, it was the right decision. But at the time, the news probably merited no more than a modest spot on page three. The reason it got bumped up was because Campaign felt indebted to one of its best sources.’

By all accounts, Charles was little short of hyperactive when it came to publicity. According to Saatchi & Saatchi’s first ever account executive, John Honsinger, the amount of publicity that Saatchis got throughout its early years was ‘largely down to Charlie or inspired by him, which demonstrates his sheer inventiveness. He would regularly phone Campaign to place stories and rumours. The effect of which was to get the industry talking and, in turn, Campaign would tip him off when an account was about to move. A story might be that a company was unhappy with its agency, which would cause them to issue a denial and sometimes result in a review of the business.’

Ron Leagas remembers Charles’s calls to Campaign, ‘Garnering favour by telling of rumours he’d picked up. In reality, the rumours initially were recycled stories he’d plucked from the columns of The Grocer magazine.’ At least two people recall Charles using a different name when ‘placing’ stories; holding his nose to create a nasal-sounding anonymity, he became Jack Robinson.

Sean O’Connor joined Saatchi & Saatchi as an account handler in summer 1974: ‘Charles had one overriding objective for the agency in those days and that was to make it famous. His ambition each week was to be the lead story on the cover of Campaign. A friend of mine had once added up all the new business wins they (Saatchis) had announced in their first two years and it came to over £30 million. This was in the days when that would be the total billings for a decent top-five agency. They’d announce anything. Their great friends, the Green brothers, once had the idea of selling on the dresses that catwalk models wore. They opened a small shop in London’s Bond Street and gave the “account” to the Saatchis. The story duly ran on Campaign’s front page as “Saatchis in £3m retail win”. This was when the agency’s entire billings were about that number.’

An early employee of Saatchi & Saatchi was the then art director (later Sir) John Hegarty, co-founder of Bartle Bogle Hegarty. In his book, Hegarty on Advertising, he recalls some publicity creation from his time at Saatchi & Saatchi:

‘Charles could invent stories out of nothing as well: there was an occasion when there wasn’t much to report, no news stories to keep the agency at the front of the trade media’s mind…On this particular occasion Charles wanted to create a story that underlined the value of his creative department, so he contacted a friend in the insurance business and agreed with this associate that he’d “insure” the Saatchi & Saatchi creative department for £1,000,000, a vast sum of money in the early seventies. On top of that, Charles decided he’d take a leaf out of the world of football and institute a transfer fee if any other agency wanted to poach one of his highly valuable creatives. The story was complete fiction. But a few days later there we all were, the creative department of Saatchi & Saatchi, on the back page of The Sunday Times business section, photographed on a bench in Golden Square posing like a football team.’

It was (designer of this book) Nick Darke’s very first week at Saatchis when the photograph was taken. For some reason (and it’s still a mystery to Darke) Charles told him he’d decided to give him the name ‘Philip James’ in the caption to the photograph.

Nick Crean became Charles and Maurice’s PA in the late 1970s. He was no stranger to the importance Charles placed on managing stories about Saatchis in the media. According to Nick, one of Maurice and Charles’s legendary exchanges of views – complete with office trashing – was caused by a front cover of Marketing Week, headed ‘A Tale of Two Saatchis’. The story in the magazine was critical of the two brothers. Charles blamed Maurice for talking to a journalist without asking him. Nick says, ‘Not only had I been summoned into the office at dawn to make sure that all copies of that week’s Marketing Week were removed from everyone’s desk and from reception, I was dispatched to buy up all the copies from all the newsagents in the Charlotte Street area.’

John Tylee joined Campaign in the mid-1980s and was amazed at how far the Saatchis would take story management: ‘The swashbuckling way in which Saatchi & Saatchi went about building its reputation was in sharp contrast to the control freakery that kicked in when it came to maintaining its desired image. While most agencies allowed you free access to almost anybody you wished to talk to, Saatchis had pulled the wagons into a circle. Only a small group of senior executives – and nobody else – were allowed to be quoted. The result was often utter farce. I once phoned a bright young Charlotte Street manager called Paul Bainsfair with the news that he was to be a Campaign “Face to Watch” and could he help me with a few career details. Sorry, he replied, he wasn’t allowed to. Only the top brass could do that.’

However, media management wasn’t the only weapon in Saatchi & Saatchi’s armoury. The fame of the agency had something of a head start. The surname the brothers were born with was a brilliant brand name. It was unusual but it wasn’t difficult to remember. One could even view it as an object lesson when it comes to naming a product, a service or a company. In short, be different, be brave. Using the name twice also hinted at a highly respectable profession, such as a company of lawyers or accountants, thus making it more client-friendly. The brothers shrewdly avoided a made-up name that might have had temporary appeal before it would quickly begin to seem dated.

The ‘establishment’ feel of the chosen name was enhanced by basing the logo on the clever choice of a classic, conservative, but elegant typeface, Goudy Old Style. The logo appeared in a number of random variations until Nick Darke formalized it and set the rules for the logo’s usage.

Ultimately, though, no one would dispute the greatest catalyst of Saatchi & Saatchi’s unparalleled household fame was winning the Conservative Party account in 1978. The style of political advertising created by Saatchi & Saatchi for the Conservative Party had never been seen before in the UK. Until then, political advertising amounted to polite or pompous, but always meaningless slogans. It was the birth of a new brand of political advertising that attacked other parties. It was aggressive, but it was also thought-provoking. Leading the charge was a poster, written by Andrew Rutherford and art directed by Martyn Walsh, showing a long queue of people outside an employment office. The headline, aimed directly at the governing political party, simply stated: ‘LABOUR ISN’T WORKING’.

It caused a sensation. Naturally, accusations of dirty tricks flew around. For instance, it was claimed that the people in the queue were agency employees, which was denied. Importantly, the creators of this controversial work didn’t remain anonymously in the shadows. Saatchi & Saatchi shared the spotlight with their client. The agency began to be mentioned by name on television and in all the press, broadsheet and tabloid alike. This was too high profile an opportunity to be missed and the moment was seized with all...