![]()

Put simply, a portfolio is a physical or virtual showcase of work. Depending on the stage a designer or illustrator has reached in their development or career, their portfolio may take one or more different forms. There is, however, one constant: because academics and employers have different concerns, the chances are the size, content and format of a practitioner’s portfolio will change the most when they make the transition from student to professional. In this chapter you will find the basics on what constitutes the best approach for your portfolio according to your chosen market, to make it an effective tool for your needs.

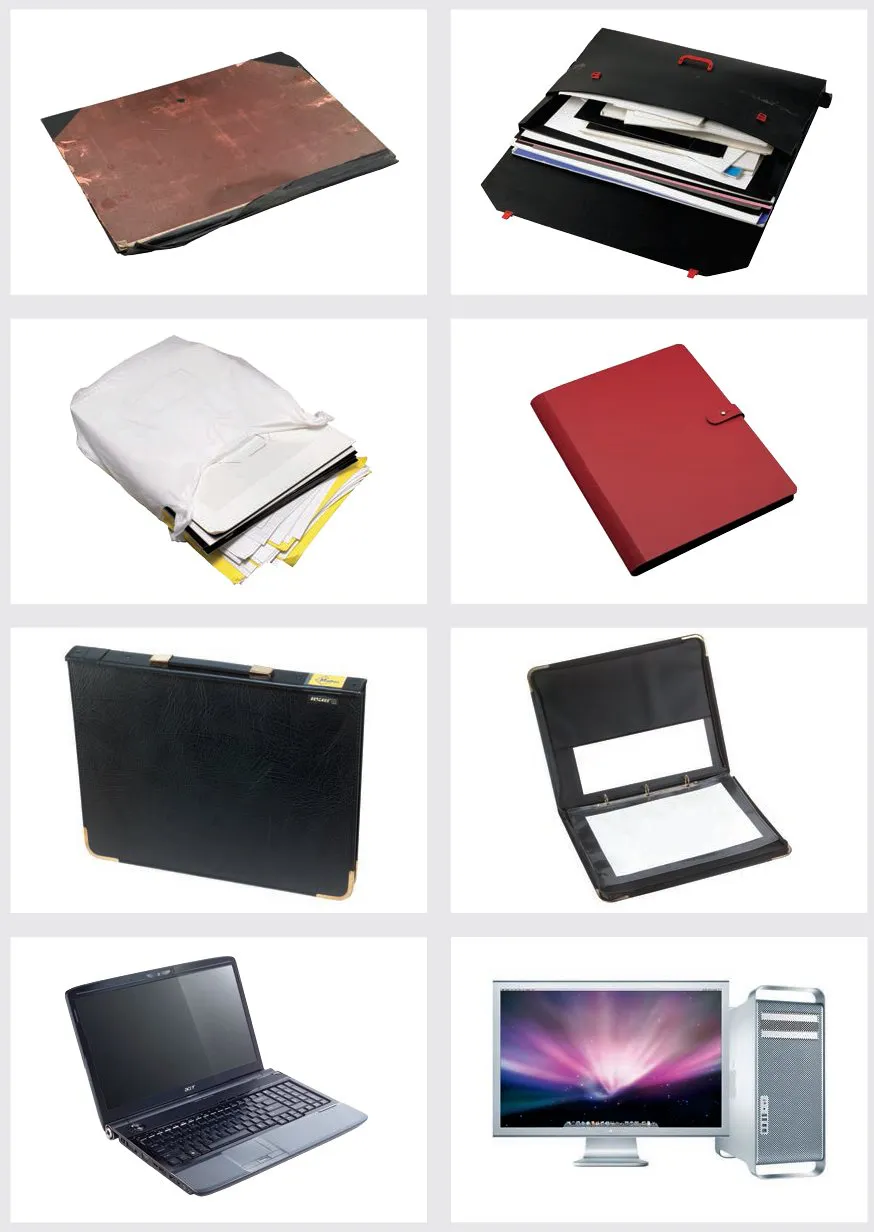

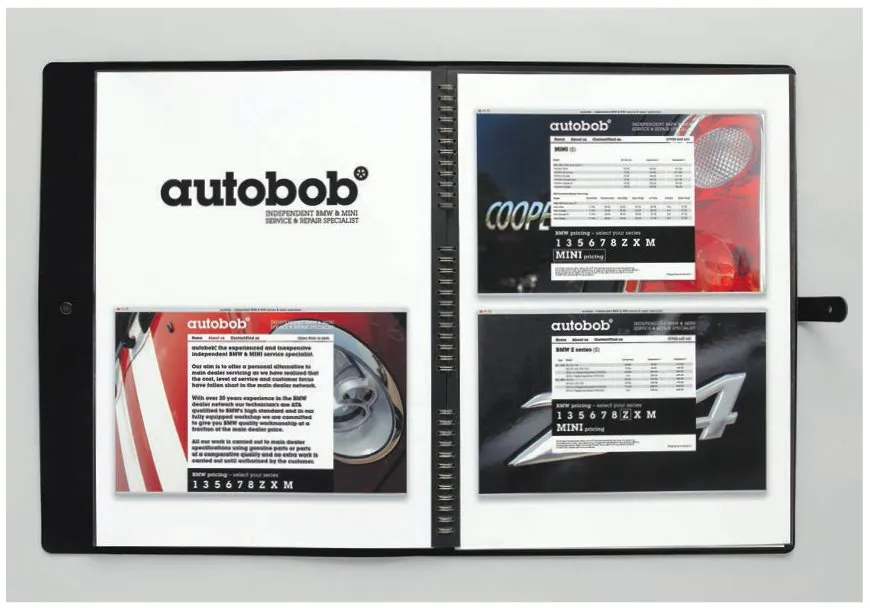

Three classic examples of how not to present work to employers or commissioners; a Pampa Spiral book with polypropylene or polyester sleeves from Prat Paris strikes a more professional note; a Mapac zip-up, ring-bound portfolio with leaves (shown open and closed) is a reliable and smart choice; samples of work, digital and otherwise, can also be accessed online through a PC or Mac, whether transported via a laptop (Acer) or at home and in the studio (Apple Mac Pro).

The Student Portfolio

Initially, regardless of where you choose to study, most art colleges look for similar qualities in the students they enrol. At foundation/undergraduate entry level, interviewing panels want to see a diversity of work including sketchbooks, life-drawing studies and self-initiated endeavours, along with high school projects. Even at this early stage, prospective students who specify an interest in design may be expected to show a flair for the juxtaposition of type and image, while, so far as would-be illustrators are concerned, panels will be on the lookout for strong drawing skills and a keen eye for colour. Experimentation across a wide variety of disciplines, such as painting, photography or printmaking, in both traditional and digital media, is actively encouraged – as is an open mind and a willingness to explore various creative paths. Be aware, though, that there’s a distinct difference between showing the range of your work and blindly including everything bar the kitchen sink in your folder on the off chance that somebody, somewhere, might like something. Your ability to discriminate between your best pieces and your less-than-finer efforts will also be under scrutiny, and will continue to be once you graduate, so it’s worth starting as you mean to go on.

In terms of how many pieces you should include, it is impossible to be prescriptive; however, using your judgement and making sure you show a wide diversity of work are the best guidelines.

At this stage a portfolio is little more than a receptacle in which to transport work. Given that you’ll probably be showing originals, and that some of these will be large, an A1 (24 × 33.9 inch) portfolio, with or without plastic leaves, tends to be the norm. In addition to bearing the hallmark of your creative personality the contents should, where applicable, be mounted up and/or displayed according to individual college guidelines. Some institutions are more prescriptive than others in this respect but meticulously presented samples, put together with obvious pride and in some sort of logical order, always make a favourable impression.

Students wishing to pursue a bachelor degree in graphic design or illustration are expected to demonstrate a distinct leaning towards their chosen subject, but not in so rigid a manner that they come across as ‘unteachable’ or unwilling to take risks. Whichever discipline you opt to concentrate on, there will be a strong emphasis on the ability to conceptualize and solve problems through image-making – hence the value placed on sketchbooks and developmental roughs. Likewise, projects you’ve initiated and seen through in your own time will be seen as evidence of commitment and self-motivation.

As a creative practitioner presentations will form a regular part of your working life so, although this is not strictly part of your portfolio, how you write and express yourself verbally can influence your chances of being accepted on a study programme, particularly if the college you choose is a popular one – a factor that is as likely to be influenced by geographical location as by a record of academic excellence. There’s every likelihood, too, that you’ll be expected to be familiar with leading contemporary practitioners within your field of interest. Aside from anything else it pays to be aware of the competition; and, from an interviewer’s perspective, it will prove you’re passionate about your chosen discipline and that your decision to study it is an informed one – again, something that will count in your favour if your institution of choice is overwhelmed with applicants.

Those who elect to study for a master’s degree have to submit a rather different portfolio – in some ways more akin to the kind they might present to a potential employer or commissioner. The contents are expected to reflect a confidence and sophistication borne of a thorough familiarity with the student’s chosen media. However, less is decidedly more at this level, so critical editing skills will once again come into play. The portfolios tend to be significantly smaller in format than the ones produced for initial enrolment in a college and, although the inclusion of sketchbooks and working roughs is equally important, a smaller selection – say 10 or 12 strong, finished pieces – will win out over a larger one that incorporates work you’re less sure of. Try to choose the samples that best reflect your unique approach to visual problem-solving or image-making.

Maturity is the key word here; in fact, in the United States (but not in the United Kingdom) it’s customary for master’s programmes to dictate that students have spent a minimum of a year in the commercial workplace prior to application. Verbal communication skills are of paramount importance. You’ll need to be up-to-date with what’s under critical debate among industry movers and shakers – and, work experience notwithstanding, your portfolio will have to make clear your ability to undertake sustained, practice-based research. You should also have a clear picture of what you hope to achieve, identifying specific areas of interest you believe would benefit from further development and exploration.

‘I would expect to see a set of observational drawings from life; sketchbooks showing the generation and development of ideas as an illustrator; a set of resolved illustrations based on specific texts (with supporting material such as sketchbooks or working sheets). Also some illustration translated into a printed context.’

Jonathan Gibbs, course leader, BA Illustration, Edinburgh College of Art, UK

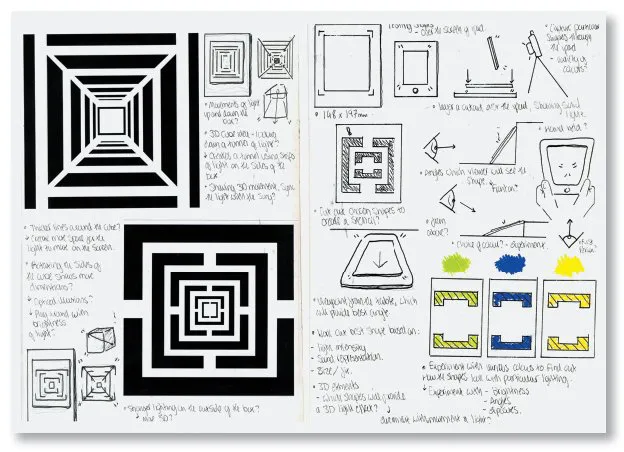

(top) Concept sketches for Loughborough University student Austin Driscoll’s Interactive Light Poster; (below) recent University of Northampton graduate Darren Custance’s online portfolio.

‘If a portfolio is totally disorganized and in a real state, I’d worry about the ability of that person to organize themselves and complete a job on time.’

Jonathan Christie, Art Director, Conran Octopus

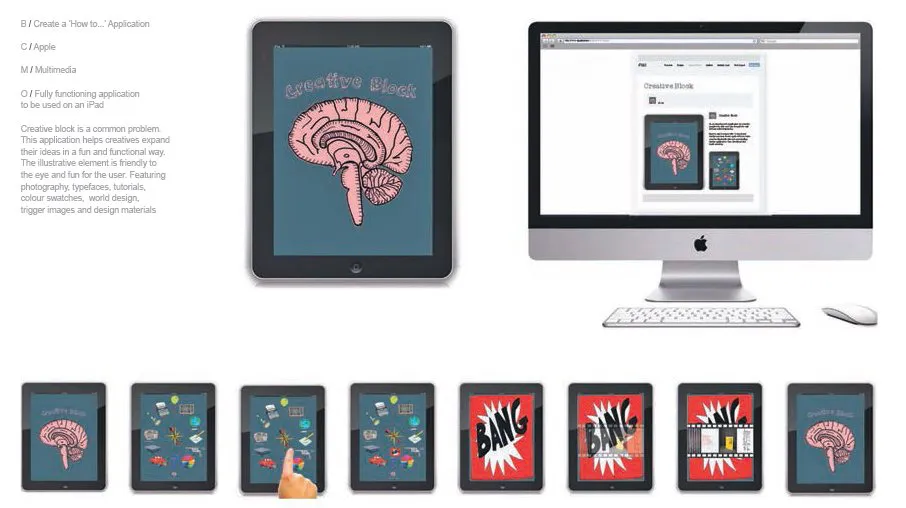

Digital portfolios can be interactive and allow you to showcase your work on a variety of devices, such as the easily portable iPad. Shown here is work from Tonia Ibrahim’s portfolio.

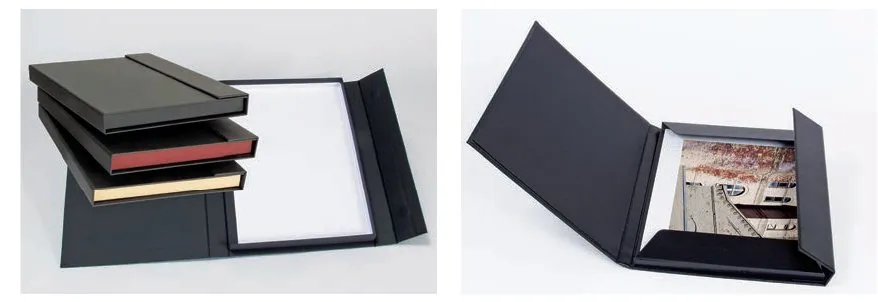

Several examples of the box portfolio format, which is particularly effective for prints that need extra attention. These are produced by US company Archival Methods.

The Professional Portfolio

Even if you graduated with flying colours there’s inevitably further work to be done on your portfolio if it’s to meet with professional requirements. To reiterate, art college lecturers and potential employers have very different agendas when it comes to weighing up the contents of a portfolio. In order to develop your skills and imagination, the college environment will have granted you the freedom to experiment, and your struggles and failures will have played an essential part in discovering where your strengths lie. Those whose job it was to nurture them were concerned primarily with the process of growth, whereas potential employers will be mainly concerned with the finished result. They don’t need to see documentary evidence of the mistakes you learnt from. You are, after all, out to inspire confidence not doubt and a patchy portfolio will do the latter. The commercial world is after quality, consistency, focus and enthusiasm – in other words, employability.

Whether you favour a print or digital approach, when it comes to assembling a professional body of work there is no prescribed industry standard, though some colleges offer guidance regarding size, format, number of samples, inclusion of roughs, mounting procedures and so forth. Others merely make recommendations, while many more prefer to leave such decisions to the personal taste of the graduate-to-be. Do bear in mind that large print portfolios are highly impractical, and there is no necessity to show very large pieces at actual size. Presenting on a laptop is an efficient way of transporting large electronic files of work and gives you personal control of your presentation. You can show your work in a small informal meeting or connect the laptop to a projection system and present it in a larger setting. You may prefer to use an interactive tablet device, which, while having a small screen, allows images to be swiftly resized for those wishing to view samples in more detail. A well-organized digital file will enable you to adjust images for multiple formats almost as easily as leafing through the pages of a print portfolio.

The physical aspects of presentation aside, striking a balance between industry requirements and personal expression is vital. College projects can sometimes cramp a nascent practitioner’s creative flow in an effort to replicate the rigid budgetary and time constraints of real-life jobs. Conversely, lengthy, deeply personal projects that bear little resemblance to anything a designer or illustrator would be asked to produce in the real world can result in a repetitive or highly uncommercial portfolio. Employers are often willing to make concessions for lack of experience or published work, but a selection of wholly inappropriate samples will baffle, bore and irritate them, and invariably jeopardize your chances of getting where you want to be.

In order to succeed in a highly competitive market, your portfolio must adequately reflect the needs of your chosen target(s). Unless your degree was highly specialized (for example, in medical illustration), it’s likely that, whether you are a designer or an illustrator, you graduated with a little bit of everything in your folder. It will be necessary to decide which of the areas you touched on during the course of your studies interest you the most. You will then need to weed out anything that is no longer relevant and replace it with some fresh work that is.

Several factors could influence the precise contents of your portfolio. If, for instance, you’re a designer and are intent on a rural or small town existence, the design companies serving the locale will probably be thin on the ground and therefore more general in nature – ergo, your portfolio must demonstrate adaptability by showing you can apply your skills in a wide variety of contexts. On the other hand, if you are planning to live in a city there’ll be far more creative outfits and, consequently, more chance that some of them will be specialist in nature. And speaking of specialization, if you have one in mind – you’d like to be a packaging designer, for example, or a children’s book illustrator – you’ll need more than a couple of relevant samples to make this perfectly clear.

When it comes to teaching students to promote themselves effectively after they graduate, some art colleges are more up-to-date than others. For instance, given society’s increasing reliance on digital technology it is surprising that not all bachelor-degree courses necessarily incorporate building a professional website in their professional studies programmes. As the world grows smaller and employers ever busier, a website is a must. It allows those in other geographical locations and time zones instant access to your work and, for some practitioners, is in effect their portfolio. Even if you choose to go an alternative or more traditional route, your website should be considered an extension of your portfolio and working practice. These methods include your CV, which should be approached as you would any other creative conundrum. You won’t convince a much-admired art director of your unparalleled typographic genius with a badly spaced, unspellchecked résumé hastily printed out on photocopy paper. It must be grammatically perfect, typographically matchless and printed out on good-quality stock.

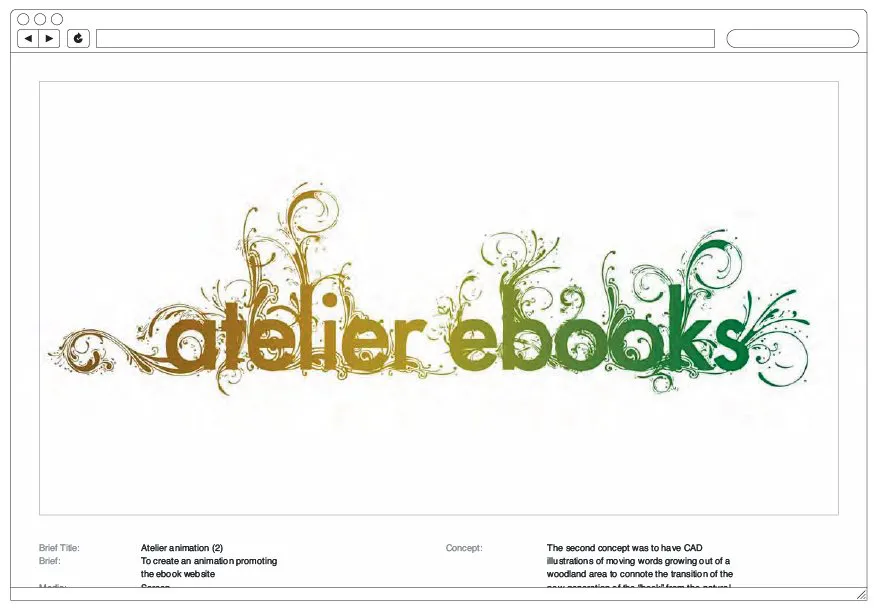

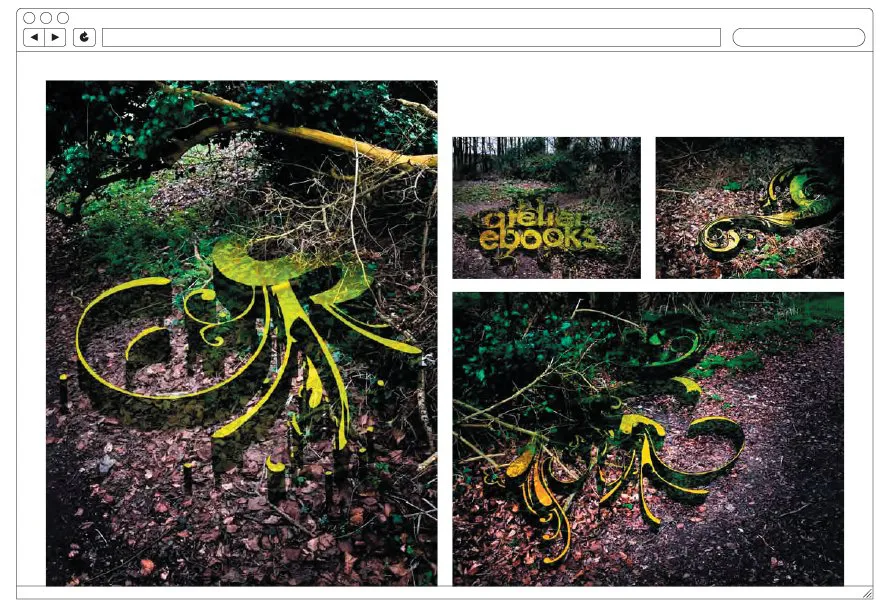

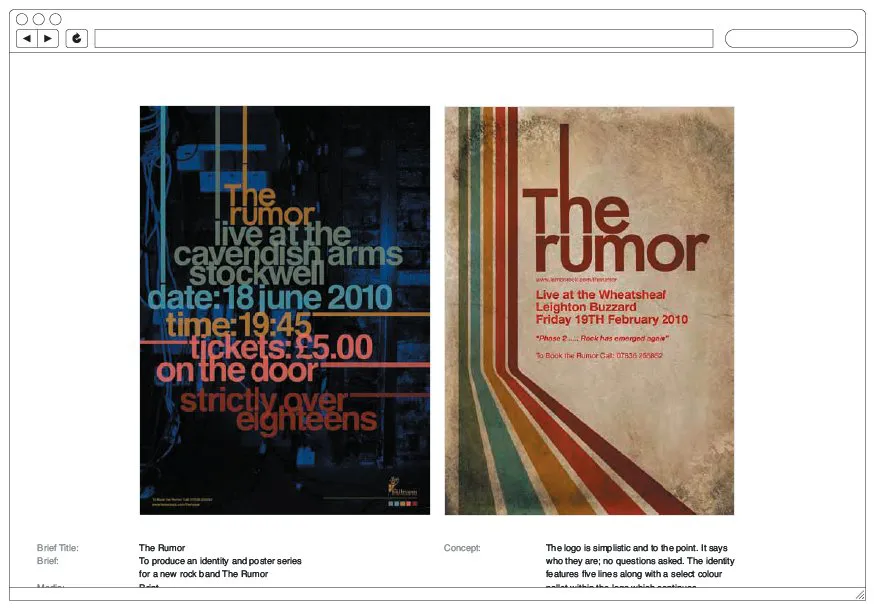

Darren Custance’s online portfolio is bold and simple in keeping with his design aesthetic and ethos. Page 14 features stills from an animation promoting an ePublishing website, while the facing page shows the development and application of a rock band’s identity in print and moving image.

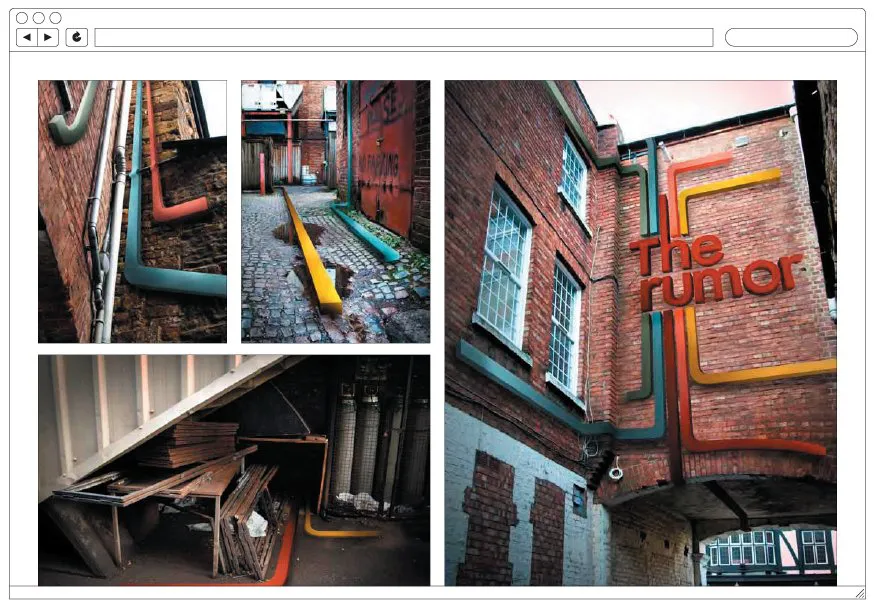

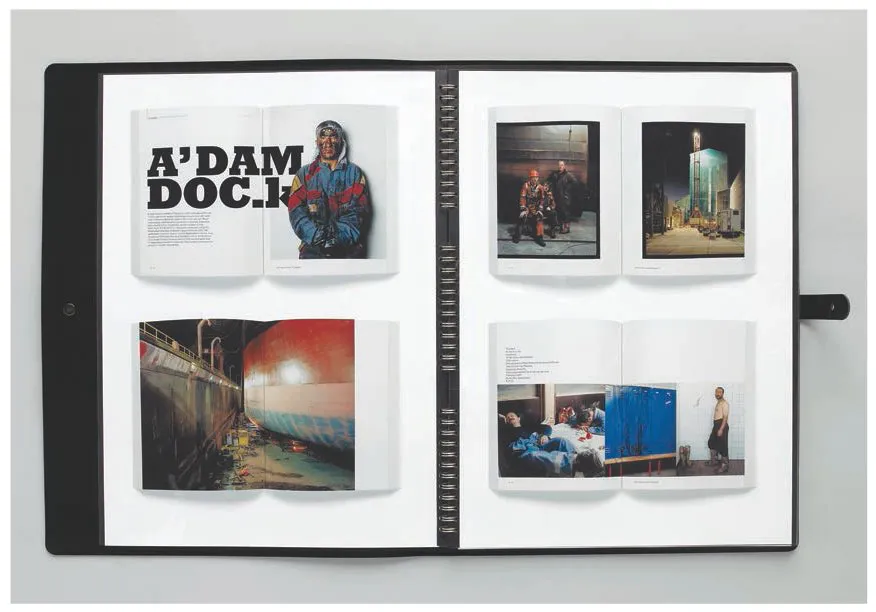

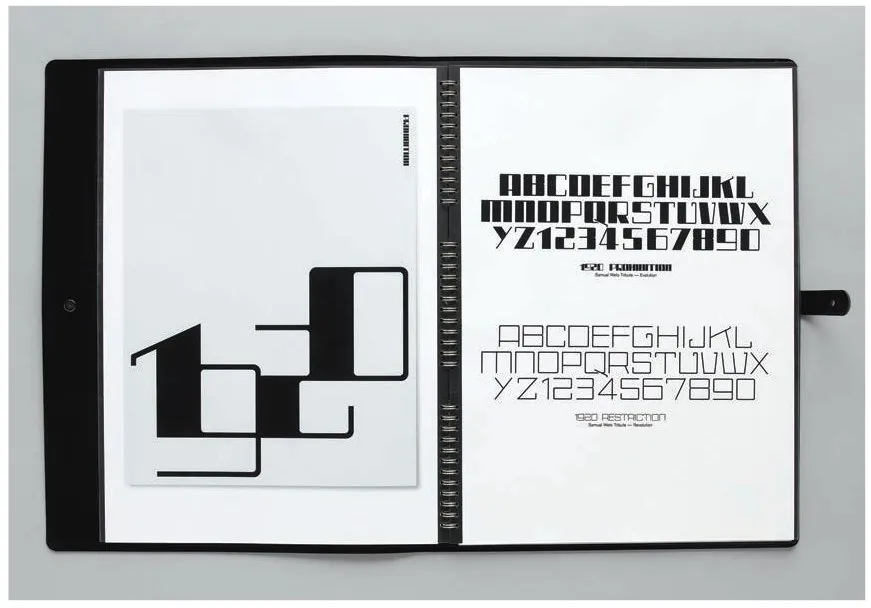

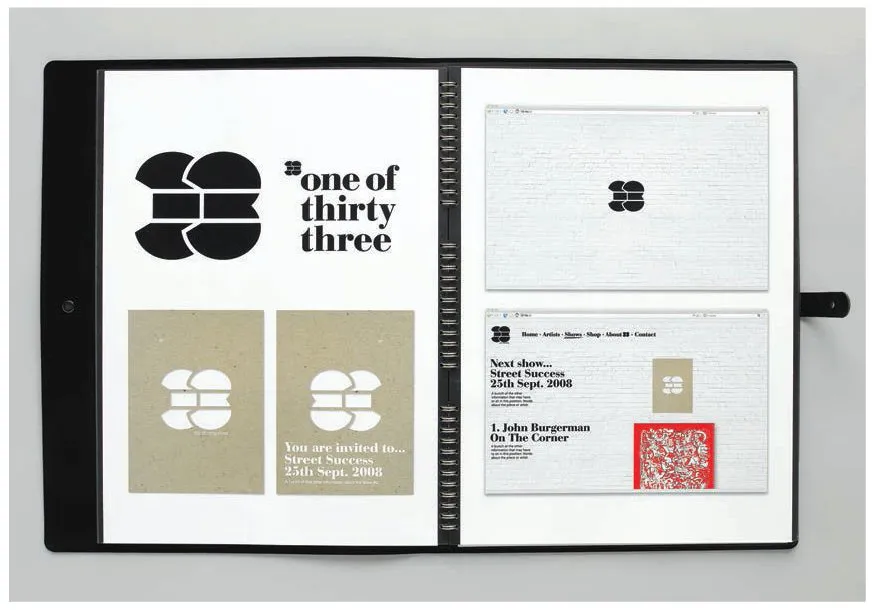

Samples from the portfolio of London-based graphic designer Matt West whose solo enterprise is called Two Seventy. As clearly evident from his portfolio, freelancer Matt works across a wide variety of disciplines, including branding, editorial, web and font design.

The Graphic Design Portfolio

A student on the verge of graduation once told me she was torn between a career in advertising and one in magazine design. Unfortunately, she had preci...