- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

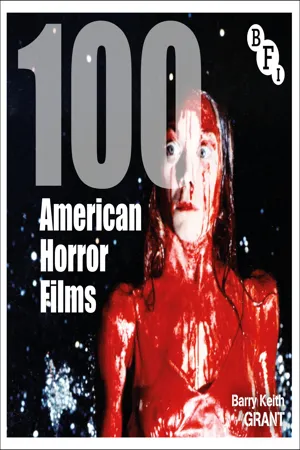

100 American Horror Films

About this book

"[A] well-plotted survey." Total Film In 100 American Horror Films, Barry Keith Grant presents entries on 100 films from one of American cinema's longest-standing, most diverse and most popular genres, representing its rich history from the silent era - D.W. Griffith's The Avenging Conscience of 1915 - to contemporary productions - Jordan Peele's 2017 Get Out. In his introduction, Grant provides an overview of the genre's history, a context for the films addressed in the individual entries, and discusses the specific relations between American culture and horror. All of the entries are informed by the question of what makes the specific film being discussed a horror film, the importance of its place within the history of the genre, and, where relevant, the film is also contextualized within specifically American culture and history. Each entry also considers the film's most salient textual features, provides important insight into its production, and offers both established and original critical insight and interpretation. The 100 films selected for inclusion represent the broadest historical range, and are drawn from every decade of American film-making, movies from major and minor studios, examples of the different types or subgenres of horror, such as psychological thriller, monster terror, gothic horror, home invasion, torture porn, and parody, as well as the different types of horror monsters, including werewolves, vampires, zombies, mummies, mutants, ghosts, and serial killers.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995)

- 2. American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000)

- 3. An American Werewolf in London (John Landis, 1981)

- 4. The Avenging Conscience (D.W. Griffith, 1914)

- 5. The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963)

- 6. Blade (Stephen Norrington, 1998)

- 7. The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick and Eduard Sánchez, 1999)

- 8. Brian Damage (Frank Henenlotter, 1988)

- 9. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (Francis Ford Coppola, 1992)

- 10. The Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935)

- 11. Bubba Ho-Tep (Don Coscorelli, 2002)

- 12. Bud Abbott and Lou Costello Meet Frankenstein (Charles Barton, 1948)

- 13. The Burrowers (J. T. Petty, 2008)

- 14. Candyman (Bernard Rose, 1992)

- 15. Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

- 16. Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976)

- 17. The Cat and the Canary (Paul Leni, 1927)

- 18. Cat People (Jacques Tourneur, 1942)

- 19. Child’s Play (Tom Holland, 1998)

- 20. Colour out of Space (Richard Stanley, 2019)

- 21. Contagion (Steven Soderbergh, 2011)

- 22. The Crazies (George A. Romero, 1973)

- 23. Creature from the Black Lagoon (Jack Arnold, 1954)

- 24. The Dead Zone (David Cronenberg, 1983)

- 25. The Devil’s Rejects (Rob Zombie, 2005)

- 26. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Rouben Mamoulian, 1931)

- 27. Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931)

- 28. Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977)

- 29. The Evil Dead (Sam Raimi, 1981)

- 30. The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973)

- 31. Fall of the House of Usher (James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber, 1928)

- 32. Fallen (Gregory Hoblit, 1998)

- 33. Fatal Attraction (Adrian Lyne, 1987)

- 34. The Fly (Kurt Neumann, 1958)

- 35. Frankenstein (J. Searle Dawley, 1910)

- 36. Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932)

- 37. The Frighteners (Peter Jackson, 1996)

- 38. Funny Games US (Michael Haneke, 2007)

- 39. Ganja and Hess (Bill Gunn, 1973)

- 40. Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017)

- 41. Gremlins (Joe Dante, 1984)

- 42. Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978)

- 43. The Hellstrom Chronicle (Walon Green, 1971)

- 44. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (John McNaughton, 1986)

- 45. The Hills Have Eyes (Wes Craven, 1977)

- 46. Hostel (Eli Roth, 2005)

- 47. House of Wax (André de Toth, 1953)

- 48. The Hunger (Tony Scott, 1983)

- 49. I Walked with a Zombie (Jacques Tourneur, 1943)

- 50. I Was a Teenage Werewolf (Gene Fowler, Jr., 1957)

- 51. In the Mouth of Madness (John Carpenter, 1994)

- 52. Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (Neil Jordan, 1994)

- 53. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Philip Kaufman, 1978)

- 54. It’s Alive (Larry Cohen, 1974)

- 55. Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

- 56. King Kong (Meriam C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933)

- 57. The Last House on the Left (Wes Craven, 1972)

- 58. Let Me In (Matt Reeves, 2010)

- 59. The Little Shop of Horrors (Roger Corman, 1960)

- 60. The Lodger (John Brahm, 1944)

- 61. Mad Love (Karl Freund, 1935)

- 62. The Magician (Rex Ingram, 1926)

- 63. Martin (George A. Romero, 1976)

- 64. The Masque of the Red Death (Roger Corman, 1964)

- 65. Midsommar (Ari Aster, 2019)

- 66. Misery (Rob Reiner, 1990)

- 67. The Mist (Frank Darabont, 2007)

- 68. The Mummy (Karl Freund, 1932)

- 69. Murders in the Rue Morgue (Robert Florey, 1932)

- 70. Near Dark (Kathryn Bigelow, 1987)

- 71. Night of the Living Dead (George A. Romero, 1968)

- 72. Office Killer (Cindy Sherman, 1997)

- 73. The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976)

- 74. Paranormal Activity (Orin Peli, 2007)

- 75. The Phantom of the Opera (Rupert Julien, 1925)

- 76. Phantom of the Paradise (Brian de Palma, 1974)

- 77. Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982)

- 78. Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

- 79. The Purge (James DeMonaco, 2013)

- 80. Race with the Devil (Jack Starrett, 1975)

- 81. Ravenous (Antonia Bird, 1999)

- 82. Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968)

- 83. Saw (James Wan, 2004)

- 84. Scream (Wes Craven, 1996)

- 85. The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

- 86. The Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991)

- 87. Sisters (Brian De Palma, 1972)

- 88. Targets (Peter Bogdanovich, 1968)

- 89. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974)

- 90. The Tingler (William Castle, 1959)

- 91. Twentynine Palms (Bruno Dumont, 2003)

- 92. Two Thousand Maniacs! (Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1964)

- 93. The Unknown (Tod Browning, 1927)

- 94. Weird Woman (Reginald Le Borg, 1944)

- 95. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich, 1962)

- 96. White Zombie (Victor Halperin, 1932)

- 97. The Wind (Emma Tammi, 2019)

- 98. The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015)

- 99. The Wolf Man (George Waggner, 1941)

- 100. Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974)

- Index

- List of Illustrations

- eCopyright