- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

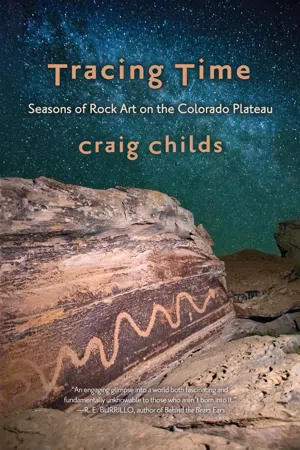

"An engaging glimpse into a world both fascinating and fundamentally unknowable to those who aren't born into it."

—R. E. BURRILLO, author of Behind the Bears Ears

Craig Childs bears witness to rock art of the Colorado Plateau —bighorn sheep pecked behind boulders, tiny spirals in stone, human figures with upraised arms shifting with the desert light, each one a portal to the open mouth of time. With a spirit of generosity, humility, and love of the arid, intricate landscapes of the desert Southwest, Childs sets these ancient communications in context, inviting readers to look and listen deeply.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tracing Time by Craig Childs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Essays on Nature. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

4Conflict

I know a warrior’s shield pecked in stone like a glowing mandala. You can tell a shield figure because of its circle, and often you see the head and legs of a person standing behind it, sometimes with a weapon sticking out. This one is big enough you could swipe it off the wall to deflect a flying projectile. Its surface is intricately decorated with pecked lines and smaller circles, representing the design that would have been painted on the shield.

After you’ve become lost in its detail, your eye will drift to the start of a second shield just next to it. This one was begun with full intention of being completed, but it never was. The first few curves had been added deeply into the rock with a sharp eye, a sharp tool, peck marks so close together you can barely separate them. You can see how a large petroglyph would have been started, a handful of small pecks outlining where the rest of the circle would go. Started with confidence but clearly unfinished, you wonder why the work stopped. Perhaps the maker passed on, or a commission wasn’t paid, protection not given. Or the reason they were putting up shield petroglyphs, conveying a warrior’s stance, a readiness to fight, suddenly came home to roost and no one was left to finish it.

Some villages burned while they were still being lived in. Canyons went empty overnight, their cliff dwellings smoldering. In the Kayenta region of northeast Arizona, where shield figures are common, tree-ring dates from cliff dwellings show that some were built and occupied for only a decade. They had shields painted up high, bright white for all to see, bold circles and weapon-wielders announcing that this place would not be easily taken. With masonry structures and timbered roofs, they seemed to be in for the long haul. Within ten years of final construction, they were gone.

A boulder outside of Moab popularly called the Birthing Scene has an image of a claw-handed woman giving birth, surrounded by an array of other petroglyphs. This has long been talked about as a women’s boulder, a place of fertility, but when Chris Lewis from Zuni traveled to see it with his nephew, it looked more to him like a battle going on. He and his nephew sat at the panel for an hour and a half, picking out its details, talking back and forth. They found images of combat and weaponry hidden in the scene. “I don’t think this is an umbilical cord,” he said. “I think it’s blood flowing from a warrior who is defending the woman giving birth.”

The warrior, he pointed out, standing tall as if protecting the woman, has an atlatl projectile sticking out of his side. Another figure, he noted, has an intentionally severed arm. A third has a raised shield and what might be an axe in one hand.

Whether this depicts a mythic battle, the birth of a hero who then goes to war and is struck by a projectile, or it represents a raid and combat while a woman is giving birth, there’s an argument for shields. Bad things happen and you don’t want to be caught defenseless.

In January, the emptiest time of year, I went to the high shield figure and its unfinished counterpart. The creek below mumbled under ice. Cottonwood trees stood bare. Frigid air roamed downhill, a stillness the canyon seems to be drifting into like a ship through fog. My perch was slickrock, my gloved hands wrapped around binoculars waiting to be used, for the day to come. I was here for dawn and sunrise, watching the last stars drift out and an inkling of light seep into cottonwoods below. I prefer this time of day, or at least this pace of waiting. The rest of the time is so much grind and go, a civilization screaming at you to stay on the ball, while here the light comes as slowly as cold molasses. A crescent moon sliced the glowing sky. Petroglyphs above me, around me, stood out through a thin broth of light, and I didn’t want to lift my binoculars to focus on them. I watched the canyon instead, eyes drawn into a gray frosting of snow and trees. Nothing moved along the snowbound creek, not an owl or fox, no breeze to stir the unfallen leaves.

Most bends of this canyon, less than a hundred miles from the Four Corners into southeast Utah, are marked with rock art. Overlooks and ground-level panels are detailed with handprints, birth mothers, flute players, snakes, hunts, and spirals. The shield above me is an ornate circle inscribed with gridded lines, curves, smaller circles, and dots. This is how shields were once decorated, in colors and patterns. Polly Schaafsma in her study on shields wrote, “The Pueblo war shield was much more than just a material protective device, but was believed to be animated by spirits and to possess magic power derived from its design that was, in turn, transmitted to its owner.”

She said that the painting on a shield, designed to blind and confuse the enemy, was more about the supernatural assistance, “deemed more important than the shield’s physical protective qualities.”

The disk above me hid the body of a standing person, two legs and feet showing, a head adorned in two pointed triangles for ears, what looks like a mountain lion head. What could be a billy club or a stone hand ax is wielded from behind. At the same time, what I call a weapon could have been a feathered prayer stick raised in a dance. Being a shield figure doesn’t automatically mean it was used in combat. A famed red, white, and blue shield was painted inside a sandstone declivity maybe fifteen miles from here, named All-American Man for its coloration. Carol Patterson told me it is not necessarily a war image, but is a cloud figure in the form of a shield. Patterson says the pictograph is a rain figure called Sun Youth, known in Acoma as Oshach Paiyatiuma, the one who carries the sun shield across the sky and arouses clouds from four directions, bringing them together to make rain. In that sense, it is not a war figure, but one with a more particular and storied past.

It’s no small thing to come to a shield panel. Even if the image were magical or narrative, not about combat, somewhere in its history, this object was wielded in conflict. I stuffed my gloved hands into my coat pockets, feeling in one pocket a wadded-up mask, a sign of the times. Two days before, a mob had stormed the US Capitol to stop the presidential election and five were dead. Shields had been shattered. Tensions in my own country were as high as I’d ever felt in my life. People and violence are not easily parted.

The shield above me seemed proud, pecked into a panel of patina as dark as burnt toast. The figure’s feet were spread as if standing on solid ground, not hanging like ghosts, but firmly planted. This was a real person in my mind, not a particular god, but someone ready to kill, ready to die.

Shields like this show up in rock art as far north of here as Montana, and out to the Great Plains where these sorts of warrior figures extend into Kansas and Oklahoma, and north to Canada. They are circles, often with a head sticking up, a pair of legs out from under, maybe showing a spear or ax. On the Colorado Plateau, the range of their designs in pictographs and petroglyphs suggests that they were painted in spirals, crosses, polka-dots, moons, suns, split-levels, and animals. Everyone had their own shield art and style of manufacture. Some may have been made of skin, while many that have surfaced from diggings around the Four Corners suggest they were woven like tight baskets, stiffer and stronger than framed leather, fair protection against an atlatl whistling at you. A basketry shield was excavated from an eleventh-century great house in northwest New Mexico, its front painted in blue-green concentric circles. Another woven shield came out of Canyon de Chelly, decorated with the painting of a frog-like figure, the center of the woven coil meeting the center of the figure’s body.

The shield petroglyph above me this morning is part of a cluster of figures pecked onto different facets of a broken-up cliff, some high above, some far below. Petroglyphs are well dressed in head ornaments and baubles hanging around their necks. They all look over arable land below as if watching for their people. They are best viewed not from up close but several rows back, down at the bottom of these staggered cliffs where you can take them all in. I’d come up to be part of the grouping, joining the gallery waiting for sunrise.

Who was behind the shield? Was it the idea of a person or an actual warrior, someone feared or relied upon? I sent pictures back and forth over email with Laurie Webster, a textiles specialist working with archaeological collections from around the Four Corners. She sent a black-and-white taken in the late 1800s of what she called a mountain lion cap, a sewn skin skullcap that would have descended down near the shoulders, once stitched with a fringe. The head had two pointed skin ears sewn onto it, and Webster believed it was made to look like a mountain lion’s head, a decoration worn in battle or for the hunt. In turn, I sent a picture I took of this shield figure, the head sticking up behind it sporting a distinctive pair of pointed cat ears. We had a match. Webster’s skin cap came from an excavation in the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde in Colorado and my shield petroglyph came from this canyon in southeast Utah, the two about eighty miles apart, a distance that could be crossed on foot in a few days. The dates she had were from around the 1200s, a time of drought, migration, and widespread conflict. She thought it might be akin to skin jaguar masks with heads and ears she’s seen in collections from southern Mexico, warrior garb. The petroglyph was probably from the same period. I take it as a fighter’s uniform, what you’d put on to either intimidate an enemy or take on powers, the countenance of the most effective predator in the land. This, to me, is the sign of an actual person. Behind this shield stood a figure in a mountain lion cap, a physical item that may have ended up in a cave at Mesa Verde.

The only other combat imagery I know in the vicinity is miles upstream at the head of this canyon. A Fremont figure with a trapezoidal body and stick-figure antenna, perhaps antlers, stands high on a busy petroglyph panel. Its one arm is outstretched, holding up a long weapon, what looks to be a leaf-shaped stone, a blade of some sort. Beside it is a petroglyph of what appears to be a severed head or a human scalp. There’s no question that this is a firm statement to watch your step. Below the figure is an engrossing congregation of rock art spanning two thousand years. Its position, higher than the other images numbering more than six hundred, by far the highest on the wall where a ladder would have been needed to reach it, suggests this is the one you pay attention to most. More darkly patinated than the rest, it is likely one of the oldest, if not the first. You wouldn’t have been able to pass through this canyon without seeing it, as if it were saying, You can enter, but don’t expect welcome.

Depictions of warriors with weapons and detached human heads or scalps are found across the plateau, one of the more common motifs. They appear as if from a collective legend like Perseus holding up Medusa’s head, or they are from domestic killings that happened often enough to record with grisly frequency and detail. One panel in Utah shows two pecked people holding up shields and projectiles, what look like spears. One of the spears is midair, flying toward a shielded person wearing horns and standing on the other side of a dotted line. The spear is about to strike the person in the shoulder or neck. Another Utah petroglyph shows someone wearing a skirt, a Pueblo kilt, standing on a rock ledge with a large, shell-like pendant on the chest. In one hand is what appears to be a severed head and the other holds a long sharp blade, the dagger that assumably did the cutting. Decapitated heads in rock art are shown with loops on top for carrying or hanging. These were trophies, fodder for ritual, the destruction of an enemy.

None of this do I find shocking. Which human society has not drawn blood, and plenty of it? The fact that it is so well represented in the art is par for the rest of the world. However much we may hold hands and sing kumbaya, other forces are rumbling.

A reservoir built in southwest Colorado inundated a valley of ninth-century AD occupation, at the time one of the largest human aggregations on the plateau. Archaeologists and diggers were sent in for reclamation before waters rose. They removed ancient burials for repatriation and mapped what sites they had time for. Work intensified when they uncovered a couple buried pit houses full of dead people. These weren’t funerary circumstances, no fine wares laid to rest with them, no jewelry spread out on their chests. They’d been cut to pieces, butchered like game animals, thirty-three people chopped into more than 14,880 bone fragments. The bloody mess had been heaved into what were once residential chambers and covered over. Victims ranged from eighteen months to fifty years old, what looks like an entire community including four neatly dismembered dogs. From what could be pieced together, researchers found evidence of weapon use on skulls, ax blows and scalping marks, and blows to the forearms indicative of people defending themselves, covering their heads as they were bludgeoned.

When dust devils blow through this valley, you pause and take stock. Some of the spirits here are deeply unsettled. You lower your head and let them pass.

Anna Osterholtz, a bioarchaeologist out of Mississippi State University, led the lab work for this site, calling what her team found “extreme processing.” She and I visited the inundated valley together, serene with water and sun, so calm and pastoral you’d never guess its history. “The actual violence would have been over quickly,” Osterholtz said. “The processing took far, far longer. There was a formula, how you take apart a shoulder joint, how you disassemble a skull.”

She’d found no remains of hands or feet from the thirty-three people. Those had been picked out and taken elsewhere, their aim unknown.

Osterholtz saw skeletons from this assemblage cut up in the same way every time, jaw bones sawed loose from one side of the face and wrenched out by hand. She calls this “performative violence,” which is violence that takes place in front of an audience. That audience may have been survivors of the massacre singled out to witness the butchering so they could return and tell what they saw, and I can only imagine their stuttering, sobbing voices. Those are the ones I pray for, even twelve centuries later. This kind of pain does not quickly depart.

“This creates in-group and out-group identity,” Osterholtz said. “These people were definitely out-group.”

Osterholtz spoke of violence with a scientific calm I found both alluring and troubling. She called violence a means of control, a functioning part of a social structure, a way of keeping order. “It is essentially a leveling mechanism,” she said. I asked her about the children and the horror of what that must have been. She said I should pay attention to the other forms of violence and conflict represented in the archaeological record, evidence on skeletons, often females of low burial status, that bear repeat injuries to the head and upper body, healed fractures, signs of domestic abuse. She pointed to what is known as Cave 7 in Utah with ninety dead Basketmaker people buried inside, many showing violent ends, signs of hand-to-hand combat with broken limbs and skulls stoved in, and weapons lodged in bones, stone points, bone awls, and the tips or blades of obsidian knives. They weren’t buried all at once, not a mass killing, but had been interred over time, a sign of ongoing deaths at the hands of others.

With this kind of violence on the table, you can see why shields would go up. No one wants to be controlled in such a way. The question I’ve often heard is who was perpetrating the violence, but this is moot. Marauding invaders or next-door neighbors, does it matter?

Shield imagery is common along a boundary that crosses Utah between Pueblo groups in the south and the more northern Fremont culture, evidence of friction between the two. We like to think it’s someone else, and no corn-loving Anasazi would ever do such a thing, but violence routinely comes from within. When one group ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction

- Handprints

- Floating People

- Spirals & Concentric Circles

- Conflict

- Horses

- Adornment

- Birth

- The Hunt

- Joined Hands

- Rain

- Galleries

- Symbols

- Processions

- Crookneck Staffs

- Ducks on Heads

- Desecration

- Children

- Sundial

- About the Author

- About the Art