![]()

PART ONE

They CAME from the SKY

![]()

1

CASTAWAYS

THE LANDSCAPE OF THE TEXAS PANHANDLE IS CALLED the High Plains for a reason. Even though the elevation in this part of Texas is less than five thousand feet, when you drive north from Amarillo on State Highway 136, the overwhelming flatness of the land creates a top-of-the-world sensation, a feeling that you are rising upon the surface of a brimming, borderless sea. About twenty miles out of town, however, the land takes on texture. Shallow gullies and grassy declivities begin to appear, like ocean swells building under the stir of a gentle wind. Farther on, the change is dramatic. The flat land suddenly disappears entirely, replaced by a beautiful broken country where the Canadian River and its tributaries have sluiced deep below the limestone caprock into red Permian clay.

This is the site of the Alibates Flint Quarries. It is an important place, one of only three locations in Texas to be designated a national monument by the federal government. But a safe guess is that most of the people who find their way to the modest little visitor center at the bottom of a winding canyon road are drawn there less by the site’s beckoning fame than by spur-of-the-moment curiosity. In truth, there isn’t all that much to see, though what you do see you could spend a lifetime thinking about. Scattered over a series of windswept mesas above the Canadian River valley are seven hundred or so pits that were dug into the ground by ancient toolmakers in search of high-quality flint for knives, spear points, and arrow points. The pits were only a few feet deep, and over the millennia most of them have filled up with soil and plant life, so they register only as shallow depressions under a carpet of native prairie grasses and yellow broomweed flowers.

But pieces of the flint that was once quarried from these pits lie all around, flakes of agatized dolomite with intriguing striations and swirling colors, most characteristically a milky, muted shade of oxblood. There are natural outcroppings of this rock as well, big colorful boulders, but the paleo and archaic peoples who lived here appear to have mostly ignored the surface rock and dug with bone axes and hammerstones to get to the unweathered flint beneath the soil. They shaped it into what archaeologists call bifaces or trade blanks, hand-sized blocks of stone that they would carry back to their slab-housed villages or nomadic camps to be chipped and flaked into working implements. These unfinished pieces of flint also served as currency in a trade network that flourished throughout North America for many thousands of years. In Texas, a state whose identity would become fused with the practice and ethos of business, with cotton, cattle, oil, real estate, shipping, aerospace, banking, and high tech, the production and distribution of flint was the first thriving enterprise.

Alibates flint went everywhere, carried along by ancient peddlers through draws and along riverbeds and game trails, traded as far away as Minnesota and the Pacific coast. These quarries along the Canadian date back to the twilight of the last great Ice Age. The people of that time and place shared the grasslands and forested savannas of early Texas with vanished megafauna like bear-sized sloths and camels and saber-toothed cats and gigantic proto-armadillos. The earliest inhabitants shaped Alibates flint into the distinctively styled spear and projectile points that are classified today as Clovis, named for the town in New Mexico near which they were first discovered. Clovis points were long, often three or four inches, and painstakingly flaked to create a groove on either side for fastening the point to a split shaft. Clovis-era hunters used these weapons to kill the great Columbian mammoths—less shaggy than their northern cousins but, at fourteen feet high, even taller—that flourished in the warming landscape below the retreating ice sheets.

The long-held archaeological conviction that Clovis artifacts represent the earliest inhabitants of North America—people who had threaded their way onto the continent when it was joined to Asia by an Ice Age landmass—has been challenged in recent years, the attacks originating from excavations at places like the Gault Site, fifty miles north of Austin, in a rich transition zone between the rocky highlands of the Edwards Plateau and the deep black soil of the coastal prairie. Some of the tools found there—made out of local chert—lie deeper than the Clovis material. And they suggest an older technology that belonged to an earlier people, a people who had not yet developed Clovis innovations like fluted spear points, and who had taken up residence in the Americas several thousand years earlier than archaeologists’ previous estimates of when humans first lived here.

Between this earliest-known period of human habitation in Texas and the first encounters with Europeans in the early sixteenth century lies an unimaginable stretch of deep time: fifteen thousand years, five hundred generations of people for whom we have no tangible history, not the name of a single person or even of a tribe. We know them only by buried artifacts in the strata of flood deposits and trash pits, by mementoes or offerings left behind in their graves, by the puzzling imagery they carved or painted on rock walls, and by the traces of illness, old wounds, and lifelong wear visible in their bones and teeth.

Four hundred and fifty miles due south of the Alibates Flint Quarries, in the desert canyon lands where the Pecos River meets the Rio Grande, are hundreds of rock shelters that were carved out of the limestone by Pleistocene rivers. The shelters are sweeping and commodious, natural gathering places for people seeking refuge from harsh weather or perhaps in search of panoramic vistas from which to contemplate their place in creation. Excavations in the soil of the shelter floors have revealed a great deal of information about how these early inhabitants lived. There are sandals and bedding woven from lechuguilla fibers, weapons and implements demonstrating the advances of Stone Age technology, the remains of earth ovens where the fibrous bulbs of sotol plants were baked for days to make them edible. But when you look up at the colorful, faded rock art on the ceilings and walls of the shelters, all you see is something our modern minds must struggle to grasp, the consciousness and cosmology of a people who long ago moved on from these painted canyons.

The pictographs feature strange, provocative forms: elongated, vaguely human shapes with antlers or rabbit ears sprouting from their featureless heads, sometimes rising with outstretched arms in a posture that suggests flight or resurrection from some dark underworld. There are bat-like creatures and headless entities in the shapes of rectangles or gourds, and scattered renderings of dead animals impaled by arrows or atlatl darts. There are waving, serpentine lines and spiky paramecium-shaped blobs that some scholars believe represent the peyote cactus buttons that might have been the means of accessing an archaic mythical or spiritual realm. These tableaux have been degraded in modern times by vandalism and pollution and by the humidity created by the construction of the nearby Amistad Reservoir, but their hallucinogenic vibe is still potent. They were painted around the time when the Egyptian pharaohs were building their tombs in the Valley of the Kings, and they hint at a similarly complex belief system, one of soul journeying and form shifting and travels to and from mysterious otherworlds.

The canyons of the Lower Pecos appear not to have been continuously inhabited. Rock shelters were abandoned when the population moved on, perhaps in response to climate changes and the rise of better hunting and gathering opportunities elsewhere. After stretches of time, other sorts of people would move in, people with different tools and aesthetics, who painted the rock in accordance with a different understanding of humanity’s origins and the soul’s destination. The already ancient designs left behind by the previous occupants might have been as inscrutable to them as the Great Sphinx was to Alexander the Great.

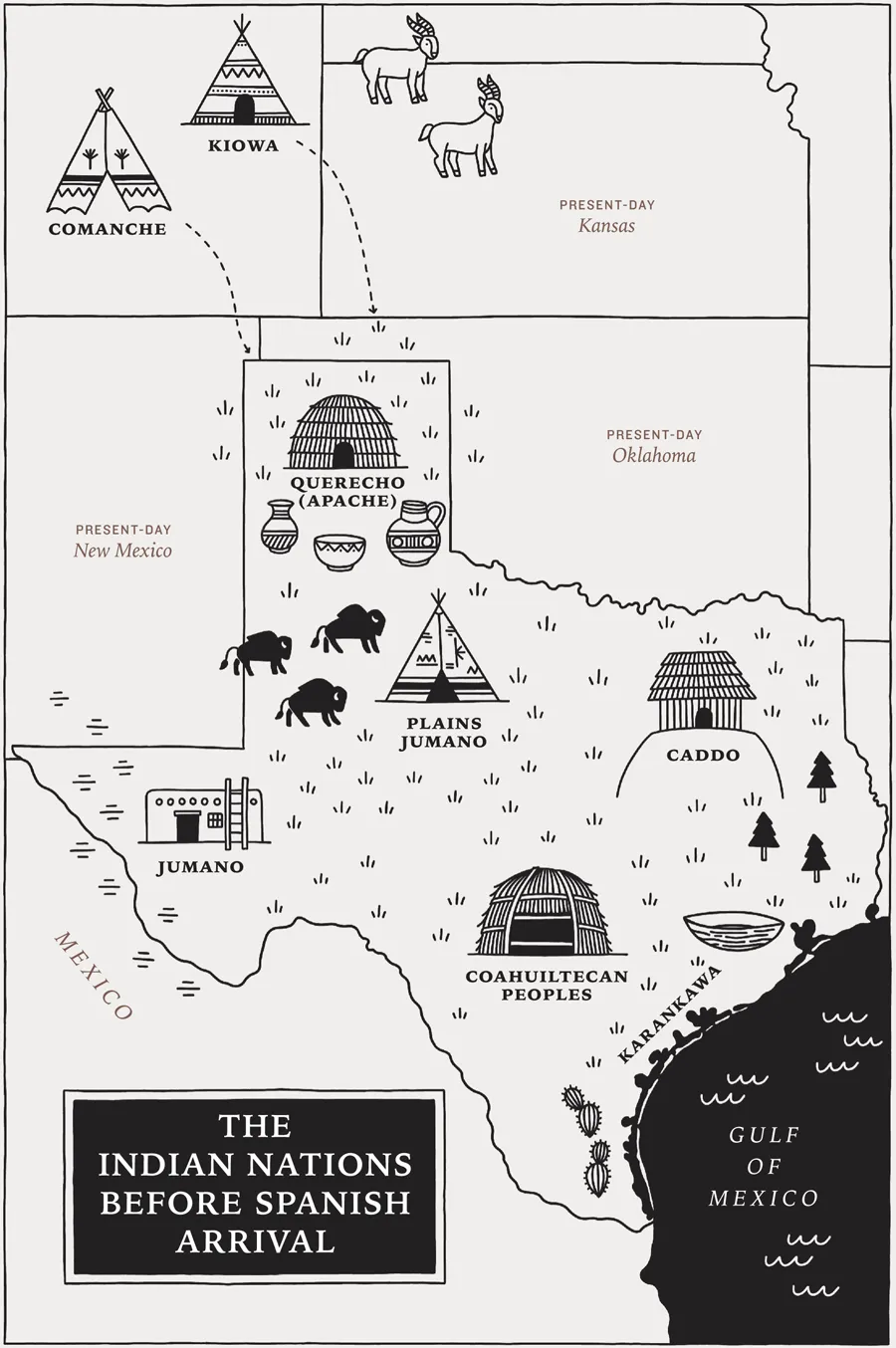

All over the region that would become Texas, throughout the unchronicled centuries, populations shifted as resources surged or dwindled, or as one tribe or band violently displaced another. (At the Harrell Site in north-central Texas, mass graves contain human bones with embedded arrow points, along with skulls whose missing mandibles were probably carried away as war trophies.) The nomadic people of the plains followed the mammoth migrations, and when the mammoths were gone—casualties of climate change, human predation, or both—these people hunted an ancestral species of big-boned, big-horned ruminant that dominated the grasslands and eventually evolved into modern bison. The expressions of human culture evolved as well, from simple thrusting spears to atlatls to bows and arrows, from designs scratched onto pebbles to intricate ornamental pottery. In the forests and deep-soiled prairies to the east, far from the deserts and drought-prone plains that lie above the great rampart of uplifted limestone known as the Balcones Escarpment, a settled farming and village life began to take hold. This part of Texas lay at the western edge of the Mississippian culture that arose in the southeastern woodlands of the continent in the centuries before the arrival of Europeans. The Caddoan-speaking people here built great ceremonial centers whose elaborate earthen temples and burial mounds can still be traced in the hummocky contours of the East Texas landscape.

By the beginning of the sixteenth century, Texas was well populated with indigenous peoples living in nomadic family groups or in settled villages that, according to one early Spanish estimate, might have had populations of up to ten thousand. They spoke a bewildering spectrum of languages, and were splintered into so many tribes and bands that Juan Domínguez de Mendoza, exploring Texas in 1684, counted sixty-four “nations” in attendance at some sort of rendezvous or trading fair on the Colorado River near present-day Ballinger.

* * *

ON THE GULF OF MEXICO LIVED A PEOPLE THAT CAME TO BE known as the Karankawas. They were divided into bands spread out along the margins of the Texas coast. Karankawas moved with the seasons. They spent the summers hunting and harvesting on the mainland prairies, and in the fall and winter they set up camp along the bay shores or paddled their dugout canoes across the lagoons to the string of low-lying barrier islands that protected the inland waters from the open Gulf. They moved seaward to take advantage of the spawning seasons of drum and redfish and speckled trout, catching the fish in weirs and nets or through the deadly accurate use of their distinctively long bows. Karankawas were famously tall; everyone who encountered them remarked on it. They were tattooed and mostly naked, their lower lips sometimes pierced with short lengths of cane, their skin glistening with the alligator grease they employed to ward off mosquitoes. They made pottery and painted designs on it with black beach tar. They lived in willow-framed huts that could be gathered up and moved quickly as they followed the food sources from season to season.

On a freezing November day in 1528, on some narrow windswept stretch of the Texas coast (most likely Galveston Island or nearby Follett’s Island), a hunting party of three Karankawa men encountered a shocking apparition. It was a man, or at least something like a man, carrying a pot he had stolen from their camp while all the people were away. He had taken some fish as well, and was either carrying or being followed by one of the village dogs. The stranger was starving and haggard. His skin was oddly pale, his hair and beard matted. His emaciated body shivered beneath the few loose rags that covered it. He looked back at the Karankawas but ignored their attempts to communicate with him and kept walking toward the desolate ocean beach. When he reached it, the Karankawas held back a little, staring in amazement. There were forty other men there, sprawled in the sand around a driftwood fire. Near them, half buried in the sand where it had been violently driven in by the waves, was some sort of crude vessel, a thirty-foot-long raft of lashed pine logs, with a rough-hewn mast and spars and a disintegrating sail made out of sewn-together shirts.

Within a half hour, another hundred or so Karankawa warriors had arrived to gawk at the castaways. The newcomers did not seem to be a threat, since they had no weapons and most of them were too weak to stand. Finally two of the men rose from the sand and staggered over to the Indians. The one who seemed to be the leader did his best to communicate by signs that they meant no harm, and he presented them with trading goods, some beads and bells that had somehow survived as cargo during whatever disastrous voyage had just taken place.

The Karankawas, who lived along the coast, were the first inhabitants of Texas to encounter Europeans. The meeting did not go well.

The Karankawas made signs that they intended to return the next morning with food. They made good on their promise, bringing fish and cattail roots, and kept coming back to feed the men for several days. One evening they returned to find the strange visitors in even more desperate shape. During the day, they had tried to resume their ocean journey, digging their raft out of the sand, stowing their clothes on board, and paddling out toward the open Gulf. Not far from shore, they had been hit by a wave, and the raft had capsized and been pounded apart against the sandbars that run parallel to the Texas shoreline. Three men had drowned, and the survivors were all now naked and so close to death from exposure that the Karankawas broke out into loud ritualistic lamentations. Then, realizing that the men would not survive the night, they got to work, some of them running off to build a series of bonfires to warm the castaways en route to their camps, others bodily picking up the starving, freezing men and carrying them to shelter.

* * *

THE KARANKAWAS WERE NOT A SEAFARING PEOPLE. THEY probed the bays and lagoons and paddled back and forth from the mainland to the barrier islands, but the open Gulf of Mexico remained a mysterious immensity beyond the reach of their dugout canoes. And far to the east, beyond the Straits of Florida, there was a much greater sea of whose existence they might only have heard through stories passed along by other native peoples. It was from the far side of this unknown ocean that the ghostlike men trying to revive themselves around the fires in the natives’ willow-framed lodges had come. They were adventurers from Spain, part of a great wave of expansion and exploration generated by the completion of a struggle that had lasted almost eight centuries, the Christian reconquest of the Muslim-dominated Iberian Peninsula. By 1492, King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella, whose marriage had allied the Catholic kingdoms of Aragon and Castile, had conquered Granada, the last stronghold of al-Andalus, the name by which Muslim Iberia had long been known. That same year, Isabella financed Columbus’s first voyage of discovery, and his landfall in the West Indies gave Spain a new horizon toward which to direct its surging national confidence, and a new world to exploit.

The men who had washed up naked on this forsaken Gulf beach were, in all likelihood, the first Europeans to set foot in Texas. (A Spanish expedition led by Alonso Álvarez de Pineda had sailed along this coast in 1519 and produced a map of it, but there is no record of them going ashore.) They came thirty-six years after Columbus, when the Spanish colonization and conquest of the Caribbean basin and Mexico were well under way, and when the invasion of the Inca Empire in Peru was about to begin. The doorway to two great continents had been breached, and it was crowded with men of rampant ambition trying to beat each other through it. Some of these men were adelantados, licensed by the Crown to risk their own fortunes in order to find and subjugate new lands. If their ships didn’t go down in a hurricane or run aground on uncharted shoals, if they didn’t starve or die of disease or get killed by the native inhabitants they had come to conquer, they would be granted titles and far-reaching administrative powers and inexhaustible wealth.

Others, like Hernán Cortés, lacked that official sanction, but they made up for it in bravado. In 1518, Cortés was commissioned by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the governor of Cuba, to explore the newly discovered coast of the Yucatán, from which two previous expeditions had returned with reports of sophisticated cities with towering stone temples and a casual abundance of gold. Velázquez had never really trusted Cortés, and as he began to suspect his commander of being a competitor and not a subordinate partner, he withdrew the commission and even ordered his arrest. But Cortés was too fast and too crafty, and the order came too late. By late February 1519 his fleet of eleven ships had sailed, heading westward across the Yucatán channel toward the Mexican Gulf Coast. There Cortés and his men encountered the unimaginable and proceeded to accomplish the unthinkable. Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec Empire, was as proud and populous as any city in Europe. To the Spaniards who beheld it after fighting their way inland from the coast, it was a sprawling, glittering, dreamlike metropolis, a place whose temple pyramids and strange sculptures and frescoes were startling in their alien beauty, and whose culture of human sacrifice—of ripped-out hearts and priests with blood-caked hair—struck their fervently Catholic minds as a devil’s pageant of horror. In only a little over two years, with a fighting force that began with fewer than six hundred men and sixteen horses but was exponentially increased by Cortés’s dynamic diplomacy among subjugated tribes primed to rebel against Aztec domination, the Spaniards had conquered Tenochtitlán and begun the work of tearing down its temples, determined to erase this wondrous abomination of a city from human memory.

There was no Aztec grandeur on the Texas coast, over seven hundred miles north of Tenochtitlán, where the Karankawa bands pieced together a subsistence existence by following the cycles of spawning fish and ripening fruits and nuts. And they could hardly have considered the desperate wraiths they had taken into their village to be conquerors. Unlike Cortés, these Spaniards had no ships, no armor, no weapons, no intimidating beasts like the never-before-seen horses. But a year and a half earlier, these men had sailed pridefully out of the harbor in Seville and down the Guadalquivir River into the open Atlantic, part of an expedition made up of five ships and six hundred people. The expedition had a grant from King Ferdinand’s grandson Charles, now king of Spain and Holy Roman emperor, to conquer and populate all the land from the northern border of Cortés’s Mexican possessions to the Florida Peninsula.

The voyage was led by a ruthless soldier and tireless schemer named Pánfilo de Narváez. Narváez had been Diego Velázquez’s sword arm in the conquest of Cuba, where he watched impassively from horseback as his men butchered the inhabitants of a village on the Caonao River. In 1520, Velázquez, still fuming over Cortés’s usurpation of the Yucatán mission, put together a powerful fleet of nineteen ships to intercept Cortés, throw him in irons, and neutralize any claim he tried to make on the plundered wealth of Mexico. Narváez, who had served Velázquez cruelly well in Cuba, commanded the expedition. When Narváez’s armada landed, Cortés had ...