![]()

Introduction

Carter Sickels

I’m writing this the day after Oregon has legalized gay marriage, and I can’t stop looking at the pictures of people lined up at the courthouse or listening to the interviews of couples who’ve been waiting for this moment for ten, twenty, thirty years. Today, Portland is a city of celebration. Friends who grew up in Oregon or who have lived here longer than me remember all too well the campaign of hate in 2004, when voters amended the state constitution to ban gay marriage. Today their joy for this hard-won fight ripples across the city. This summer, I’ll be attending my first gay wedding, at least the first one that is legally recognized by the state.

Twenty years ago, who would have thought that queer couples would actually be able to legally tie the knot? It’s been a thrilling past three years — DOMA overturned, and nineteen states and counting have granted the freedom to marry to LGBTQ couples. My own feelings about marriage are, like so many in the LGBTQ community, complicated. I’ve been a part of the queer community for most of my adult life, and I never gave marriage much thought. A white transgender male, I’m privileged in ways that so many other queers are not, and yet still I must fight for recognition in both the straight and gay worlds. Over the years, instead of marriage, I’ve had other things on my mind: coming out to myself as trans; coming out to my family as trans and gay; accessing health care and paying for surgery; navigating whether to disclose my trans identity in a variety of situations (some of which are potentially dangerous); finding acceptance in the LGBTQ community which often disregards (or excludes) the T; and being recognized and accepted as a gay man, among other issues.

My roots are queer and feminist, and I understand the critique of marriage as a problematic, patriarchal institution. But I also understand the desire to marry, and one day perhaps my partner and I will. There are the basic legal protections marriage affords, taxes and health care and partnership and visibility — so many of us either lived through or have read the stories from the ’80s about men who were denied hospital visits with their lovers dying of AIDS, who were not allowed to attend their funerals. But the freedom to marry goes beyond the legalities: why not celebrate our love with our friends and family as witnesses? Why not throw a big party? I believe queers can still queer marriage, turn it into something new, glittering with possibility.

Now is an exciting and interesting time to be queer in America. Marriage equality is all over the news, and acceptance of LGBTQ people is on the rise. Queers are more in the public eye. The first out gay NFL player kissed his partner on national TV — and network news channels aired it without batting an eye. Trans activists Laverne Cox and Janet Mock appear on national TV programs, openly discussing their experiences as trans women of color. Pictures of queer couples gloss the pages of major newspapers. Yet while we in the United States are experiencing a growing acceptance of sorts, in contrast to countries that are blatantly persecuting their LGBTQ citizens — Russia and Uganda, for example — we have not achieved full-lived equality. Just read the online comments that follow any LGBTQ news story, and you’ll be depressed and revolted by all the hate. Or look at the pro-discrimination efforts creeping up in places like Arizona and Oregon as well as the attempts to repeal existing antidiscrimination measures, such as in Pocatello, Idaho.

There is still so much work to be done.

Our fight for equality must be multi-issue and intersectional, and we must stand up for the most vulnerable in our community. Issues faced by the LGBTQ community include fear of living openly, lack of job protection, lack of access to equal health care, racial inequality, and poverty. LGBTQ people are far more likely than any other minority group in the United States to be victimized by violent hate crimes — this is especially true for trans women of color. Gay, lesbian, queer, and bi youth are four times more likely to attempt suicide than their straight peers; nearly half of young transgender people have seriously thought about taking their lives, and one-quarter report having made a suicide attempt, according to the Trevor Project. In a report published by the Human Rights Campaign, 92 percent of youth say they hear negative messages about being LGBTQ through school, the internet, and peers. Multiracial transgender and gender nonconforming people often live in extreme poverty, with 23 percent reporting a household income of less than $10,000 per year, which is almost six times the poverty rate of the general US population at 4 percent (The Task Force). There are still no federal laws protecting LGBTQ individuals from employment discrimination. Twenty-nine states still don’t have laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation, and thirty-two states don’t have laws prohibiting discrimination based on gender identity.

There is still so much work to be done.

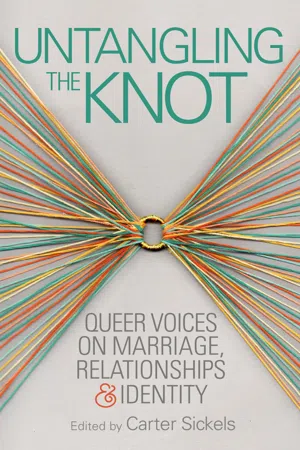

Neither I nor the editors at Ooligan Press had any idea who the authors or what the content would be for this book. Ooligan’s staff, made up of graduate students at Portland State University, intended Untangling the Knot to explore LGBTQ issues that the national marriage conversation left out, and to feature only writers from the Pacific Northwest. I joined the team as the editor, and a few months into the process, we decided to expand rather than to limit the call, and dropped the Pacific Northwest requirement.

The call for submissions was intentionally broad, to “add fresh voices to an ongoing conversation about the barriers to true queer equality. These include, but are not limited to, experiences with health care and employment, definitions of family and partnerships that extend beyond the nuclear or monogamous traditions, definitions of home, explorations of visibility, of equality, and more.” With marriage in the spotlight, what issues get pushed to the back burner? Who falls through the cracks? We didn’t want the book to be a platform for a debate on marriage, but rather to be a rich, open space for a multitude of voices on marriage and beyond. We wanted to know what queer people had on their minds.

Over a period of several months, as I read through the submissions, I began to see trends and themes, and slowly, a book began to take shape. I was struck by how many of the writers at least touched on the pain they’ve experienced in regards to their biological families; despite cultural and social shifts in acceptance of LGBTQ people, parental silence, denial, and rejection are still real and significant causes of pain for so many. Even as we create new families and find acceptance in so many aspects of our lives, we still carry with us our parents’ shame. Many of the writers also remind us that despite the legalization of marriage, homophobia is still deeply entrenched in our culture. There are many queer couples who are legally married and yet are afraid to walk down the streets holding hands.

There is still so much work to be done.

Untangling the Knot examines and celebrates the complexities of queer lives. Most of these essays are personal essays about lived experiences. These twenty-six writers reflect on marriage and relationships and identities. They explore the complexities of what it means to be queer and to be married. They write about trans identities. Queer children who are bullied. Health care and battling cancer. Surviving parental or spousal abuse. They write about lack of resources and legal protections. They give testament to our LGBTQ history and ancestors, and to the power of activism. They explore the beautiful varieties of queer relationships and families. Many of the authors are married, while others hope to be, and still others have created relationships that challenge traditional definitions of marriage. What the writers in this book have in common is their desire for recognition of all aspects of their lives, and to tell the complex stories of their lived experiences.

I wanted to publish new voices and include a diversity of perspectives. The majority of the essays were unsolicited, and for at least a quarter of our writers, this is their first published work. I’m also proud to include many writers who live in rural, conservative areas of the United States — important voices the national LGBTQ conversations often leave out. And yet, there are too many gaps, too many voices and perspectives that are not in these pages — for example, the voices of people of color are underrepresented here, and I also wish we had heard from more trans women, not only for the sake of diversity, but in order to examine the experiences of people from our communities that shed light on the issues that we should be focusing on and giving energy to.

Still, I see this book as one small step in the conversations we must have, an invitation to others to tell their stories and write about the struggles, celebrations, and issues we will continue to face long after marriage is legalized in all fifty states.

Perhaps this book is not about untangling the knot but, instead, about tangling it. And that’s a good thing: queerness is about contradictions, possibilities, and challenging the old and new. Now, it’s time to celebrate in Oregon, and also to continue the hard work. As US district judge Michael McShane wrote in his opinion striking down the marriage equality ban in Oregon, “Let us look less to the sky to see what might fall; rather, let us look to each other…and rise.”

— Carter Sickels May 20, 2014

We Are Not “Just Like Everyone Else”

How the Gay Marriage Movement Fails Queer Families

Ben Anderson-Nathe

I recently attended an annual fundraiser for a high-profile LGBT nonprofit organization. Since they run multiple programs, some of which I support, I had no idea until I arrived that the entire event was dedicated to raising funds for what was billed as “marriage equality” (a term I loathe for many reasons). An hour into the event, sitting at a round table full of well-intentioned, middle-aged, upper-income, white gay men, I’d had my fill of the marriage movement’s rhetoric, which positioned queer people’s claim to equality in the context of sameness. Based almost solely on the assertion that our relationships are no different from straight people’s, the movement contends that we therefore deserve what others have. “Our love is just like your love,” “Our family is just like your family,” “We’re committed and monogamous, just like you.” These and other refrains echoed throughout the room, resulting in applause and bidding paddles being raised to donate money toward the final frontier of gay equality: marriage. Contemporary arguments for legalizing same-sex marriage are predicated on a narrative that says our relationships are just like yours. Therefore, to recognize yours but not ours is discriminatory and perpetuates inequality. And here is my struggle with that rhetoric: I am one of those well-intentioned, middle-aged, upper-income, white men, but my queer family is most certainly not “just like any other.”

I do not want equality, with its demand that those of us on the margins must assimilate to norms that remain unquestioned, rather than transforming those norms altogether. I do not want to achieve social recognition for my family if that recognition hinges on my willingness to restructure my relationships according to the narratives and norms presented to me through conventional legal marriage. I do not support the further fracturing of queer communities such that only two-person monogamous relationships are granted validation (because those relationships are familiar enough to a dominant norm that the oddity of their same-sex-ness can be excused). I certainly do not want the pressing concerns of the most vulnerable members of my community (employment, housing, access to physical and mental health care, immigration protections, and so much more) to be sidelined in pursuit of the much more luxurious interests of people like me. Equity? I’m on board. But equality, and specifically equality signaled by access to marriage? Not so fast.

Much as I sometimes resist admitting it, I am an academic. I have been an activist (I hope in some ways I still am through my writing and my teaching). I am also just another queer person living with my queer family in the Pacific Northwest. From all three vantage points, I am concerned about the agenda my community seems bent on pursuing. This essay presents my attempt to tell my story, pulling all three parts of myself into alignment and adding my voice to a chorus of others in resistance to the mainstream gay rights movement’s focus on “marriage equality.”

Let me be clear at the outset: I am not ...