![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Water-Reallocation Challenge in California and the West

“[Between 1995 and 2020,] California’s population is forecast to increase by more than 15 million people, the equivalent of adding the present populations of Arizona, Nevada, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Utah.”

—1998 California Water Plan Update (DWR 1998a, p. ES1–4)

A discussion of water reallocation begins with four questions: How much water is available? Where is it now? Who needs it? How will it get from those who have it to those who need it? In answering these questions for California, our starting point is an overview of the state’s evolving circumstances of hydrology and demography as well as the legal doctrines that define who has water rights and what the rights entail. Historical, political, social, economic, and ecological perspectives are then woven in to develop a fuller picture of the state’s water-supply challenges. After California’s features are discussed, this chapter presents a comparative perspective, describing conditions in four other western states: Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Colorado.

Water Reallocation: A Key Issue in California

Unlike the situation in some parts of the United States and the world, the water challenges facing California do not emerge from a basic scarcity of the resource. An average of 200 million acre-feet (maf) of precipitation is deposited in California annually.1 Some regions receive as little as 4 inches per year, while others receive more than 60 inches. The state also has historically appropriated roughly 7 maf of water from the Colorado River and the Klamath River. Given California’s population of 33 million, this quantity of annually renewing water is more than four times what some analysts believe is a minimum for agricultural self-sufficiency. In fact, California is one of the world’s leading exporters of agricultural commodities, and this performance is fueled in part by the abundance of water.

Of the state’s precipitation, two-thirds is consumed through evaporation and transpiration by plants. The remaining one-third comprises the state’s annual runoff of about 71 maf. The state also takes advantage of vast groundwater reserves, in an average year withdrawing about 14 maf of the estimated 850 maf available. These natural storage basins supplement California’s water during the dry months and during drought years. Since the groundwater reserves are replenished at a rate of 12.5 maf/year, the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) estimates an annual overdraft of 1.5 maf of groundwater. In other words, Californians are mining groundwater faster than it is being recharged by precipitation. A small but growing additional year-round source of water is urban reclaimed water, which is expected to provide a reliable annual supply of almost 600,000 acre-feet (af) for urban and agricultural uses by 2020. A portion of total state supply goes to the maintenance of healthy rivers, estuaries, and wetlands. In average precipitation years, the flow utilized for ecosystem maintenance is 36.9 maf, whereas in drought years the amount used drops as low as 21.2 maf. Thus, in an average year, roughly 42.6 maf is available for agricultural and urban uses. Agricultural production currently uses roughly 80 percent of the available 42.6 maf.

FIGURE 1.1

California’s Average Annual Precipitation

Source: U.S. Geological Survey, National Water Summary 1985-Hydrologic Events and Surface-Water Resources, U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper No. 2300 (Reston,Va.: U.S. Geological Survey, 1986).

As shown in figure 1.1, most of California’s precipitation falls in the eastern and northern parts of the state. A portion of the precipitation, much of which arrives as winter snow, is captured in reservoirs during the spring thaw and then released throughout the dry, hot summer and autumn months. A combination of dams, aqueducts, and pumping stations—constituting the most developed water system in the world—aug—ments natural rivers and delivers water from the mountains to Central Valley agricultural regions and coastal population centers.

Changing Patterns of Water Demand in California

As in most of the western United States, water in California was originally allocated to serve an agrarian economy. The federal government’s primary mission was to “reclaim” wildlands and create opportunities for westward migration, homesteading, expansion of agriculture, and economic growth. As a result of this pattern of expansion, economic and political power came to reside in rural areas, not cities. Irrigation districts and individual farmers locked up the lion’s share of California’s developed water, in the form of either renewable long-term contracts or permanent rights.

As have other western states, California has been undergoing a transition in its use of freshwater resources. Net water use in the early 1990s included 80 percent for agriculture, 16 percent for urban regions, and 4 percent for recreation, wildlife, and power generation (MacDonald 1993). The largest agricultural users in terms of acreage were cotton (1.5 million acres), irrigated pasture and alfalfa (1 million acres each), and rice (0.5 million acres). Water use in the state’s agricultural regions peaked around 1980 and has been slowly declining since then. Statewide demand continues to grow but at a historically low rate, bolstered by demand from urban regions, which is growing at a rate of roughly 64,000 af/year.

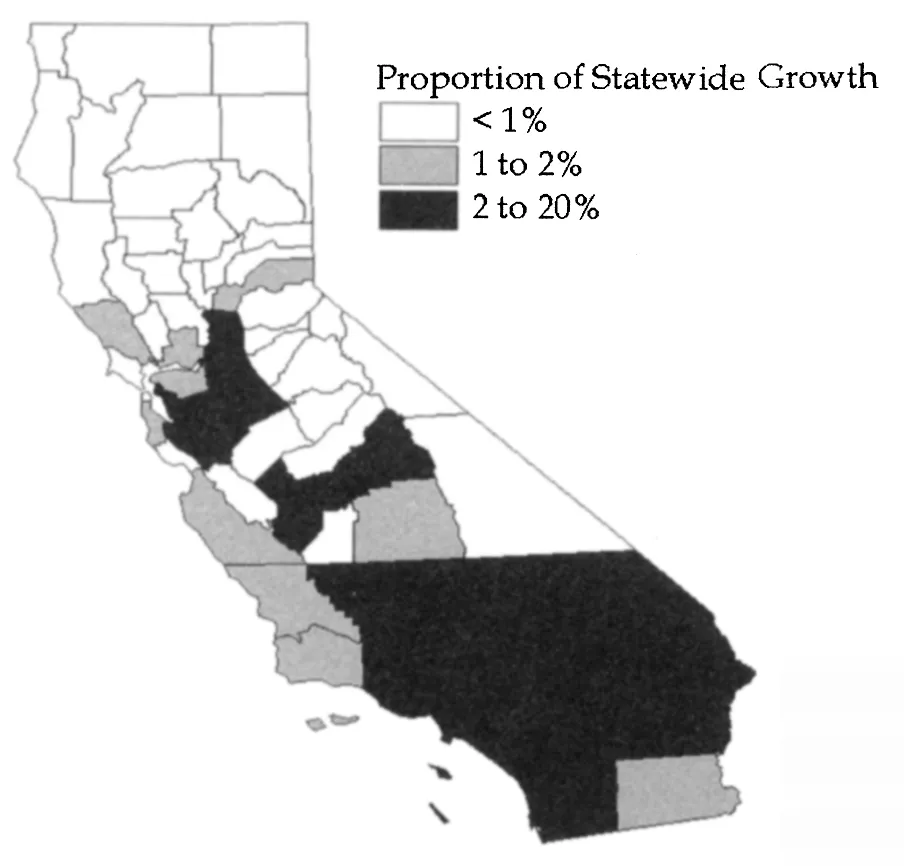

Both aggregate demand and the pattern of use are expected to change in California as population grows from 1995’s roughly 32 million to the 47.5 million projected for 2020 (DWR 1998b). Figure 1.2 highlights projected regional trends in population growth. When these trends are compared with the distribution of rainfall shown in figure 1.1, California’s water-transfer challenge stands out in stark relief.

Underscoring the urban-suburban focus of California’s future water needs, in 1995, 110 new towns and major subdivisions were in the planning stages. These were expected to accommodate 2 million new residents; 30,000 acres of commercial, industrial, and office space; and at least forty-four golf courses (Arax 1995). These projects will require 0.6 maf of water on a long-term basis.

Just as growing populations require long-term rights to water, industry does as well. Industry uses water to cool energy-generation equipment, for cleaning purposes, as inputs to production, and for consumption by employees. A firm evaluating alternative sites for a multimillion-dollar factory may make the certainty that sufficient water will be available over many decades a decision criterion. Long-term rural-to-urban transfers therefore are consistent with the long-term water-use needs of a state’s growing industrial sector (Kay 1994). The fact that industry requires a consistent, reliable year-round supply of water stands in contrast to California’s patterns of seasonal precipitation and runoff and to the changing seasonal demands of much of California’s farming sector.

FIGURE 1.2

Projected Population Growth in California by Region, 1995-2020

Source: California Department of Finance.

Environmental needs for new water resources are also growing. Efforts to restore salmon runs on the San Joaquin River and other rivers require dedicated instream flows, even when the state is experiencing a drought. Efforts to restore wetlands require new appropriations for proposed wetland regions, and efforts to restore the historical seawater—freshwater balance in the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento—San Joaquin Delta (Bay-Delta) region require new dedicated flows of freshwater as well.

The 2000–2020 scenario that emerges is one of California’s agriculture giving up water (losing 2.3 maf, or 7 percent of current annual usage), urban areas acquiring water (gaining 3.2 maf, or 36 percent over current annual usage), and environmental uses increasing by about 100,000 af/year (a 0.1 percent increase) (DWR 1998b). The resulting anticipated annual shortage of 1.0 maf may be compounded by the loss of as much as 900,000 af/year of Colorado River water, by the possibility of additional water being dedicated to the Bay-Delta ecosystem, and by efforts to end the overdrafting of California’s aquifers. If current patterns of demand and use continue in California, with its existing facilities, by 2020 the state could fall short of meeting its water needs by 2.4 maf in normal years and by 6.2 maf in drought years (DWR 1998a).

Location of water use is expected to shift from northern and central agricultural regions to the southern coast, consistent with projected regional demographic growth. Transfers of water from north to south are not new to California. Millions of acre-feet of water are already transferred from the northern and eastern mountains, where water arrives as rainfall and snow, to the central and coastal areas. Growth in demand is expected to be highest in the southern coastal region (0.9 maf, or a 17 percent increase over current annual usage), and the neighboring South Lahontan region (0.3 maf, or a 45 percent increase over current usage). This scenario of change is consistent with demographic growth in which urban population density grows and new suburbs are attached to existing urban areas on the southern coast.

One indicator of how demographic change in the twentieth century favored California’s urban sector over its rural sector is the number of state legislative representatives representing rural versus urban regions. In 1902, roughly 25 percent of California’s forty state senators represented primarily urban districts. By 1990, that figure had grown to roughly 67 percent. Similarly, between 1902 and 1990, the percentage of state assembly members representing primarily urban districts rose from 35 percent to 70 percent. This long-term trend toward urban concentration seems to be continuing in California. Out of fifty-eight counties, the five largest in terms of population, all urbanized and located along or near the Pacific coast, absorbed 2.9 million new residents between 1980 and 1990, or 47 percent of the state’s total population growth.2 Los Angeles and Orange Counties alone grew by nearly 2 million people.With the trend shifting toward more support for urban interests in legislative bodies, the farm sector is that much further challenged to maintain its historical control over the bulk of the state’s developed water.

The Legal Context of Water Reallocation

Legally, there do not appear to be strong barriers to changes in current patterns of water ownership and use. California’s system of water law is more complicated than those of most states because it recognizes the water rights of both riparian users (owners of land adjacent to waterways) and appropriators (parties who have built conveyance structures from waterways to the place of use). Most states recognize only one type of right. Under either doctrine, the easiest way to transfer water rights is to transfer land rights and include the water rights in the deal. This is, in fact, the only way in which riparian water rights can be transferred, since riparian rights are considered to be appurtenant to, or inseparable from, the land. Appropriators, however, usually have the option of transferring ownership and changing the point of diversion from the waterway, the timing of diversion, the point of return flow, and the use of the water. Long-distance transfers from one water basin to another also are permitted. That means that a water market in California could include agricultural-to-urban transfers, but it would be a market among appropriators or those who contract with appropriators for water deliveries.3 It would not involve riparian rights.

The two key principles of the appropriative doctrine are “first in time is first in right” and “no harm.” The earliest appropriators get to satisfy their established use patterns first, even in a drought year, while those who began appropriating later wait their turn.4 During a drought, the most junior (most recently established) appropriators may not be able to divert any water at all. When a water right is transferred, it retains its ranking in comparison with those of other appropriators on the same waterway. But any action taken must not harm the established rights of other appropriators (as well, in California, as riparian users). That means that new diversions are not allowed on waterways that are fully appropriated, and a water transfer would not be allowed if it harmed the ability of other appropriators to utilize their rights.

The “no-harm” portion of the appropriative doctrine protects only those parties who hold water rights. The rights of other interests—environmental protection, rural towns, recreation, farmland, or open-space preservation—are protected by other statutes, such as that requiring a...