![]()

Chapter 1

Defining Digital Portfolios

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better."

—Maya Angelou

Too much assessment in schools today is done to students instead of with students. Even when the assessment reveals more than a score, the student or teacher does not have much say in the process. That said, within the context of the classroom, teachers still have considerable authority over how they can guide their students to improve daily. For example, through thoughtful language choices that are focused on a growth mindset, students can develop agency—the belief that things such as our intelligence and life's outcomes are changeable (Johnston, 2012). These teacher-student conversations bring students to focus on what they are doing instead of just how they are doing. In such a context, numbers and grades no longer direct these discussions.

In this chapter, we explore how digital portfolios can help students and teachers make this shift toward a partnership approach to assessment. A working definition, along with types and examples of digital portfolios, is offered to build a common understanding. We also look at the history of portfolio assessment in education, including why it seemed to disappear—along with reasons for its resurgence. The chapter ends with a framework for thinking about digital portfolio assessment through the lens of good pedagogy. Though technology is here to stay and has brought a lot of good into our world, the tenets of strong instruction are timeless.

Defining Digital Portfolios

Using technology to aid teaching and learning is not a new concept. Interactive whiteboards, the Internet, and wireless access are commonplace in schools. Recent technology, such as learning management systems like Edmodo and Schoology, has provided teachers with the ability to facilitate some classroom activities online. What is new is how technology can and should be leveraged to transform teaching and learning—instead of just enhancing it. This requires a shift in practice. Both teachers and students can improve in their work with the inclusion of digital tools when they are thoughtfully integrated with instruction.

Digital portfolio assessment is one such approach that could build a learning partnership. David Niguidula (2010) coined the term digital student portfolios, defined as "a multimedia collection of student work that provides evidence of a student's skills and knowledge" (p. 154). I've expanded on this definition and consider digital student portfolios to be dynamic, digital collections of information from many sources, in many forms, and with many purposes that better represent a student's understanding and learning experiences.

How we define digital student portfolios, though, is secondary to how we use the related technology in the classroom. Strong instruction with technology embedded as a necessary resource is preferable. For example, implementing a 1:1 program (i.e., one digital device per student) without any type of forethought, research, or planning does not lead to significant learning outcomes. In fact, such an approach could exacerbate achievement gaps for at-risk students who are not familiar with the technology (Toyoma, 2015). The change we want to see in schools—and that we hope technology will help facilitate—requires more than just a financial investment.

Three Types of Portfolios

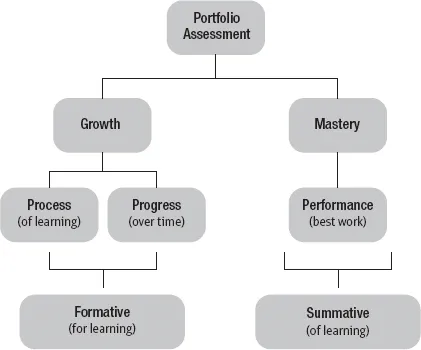

Let's take a deeper look at the purposes of portfolios and the different types of portfolios that have been used in schools (Figure 1.1). Literacy professors Richard Allington and Patricia Cunningham (2006) offer clear definitions for this assessment tool and process (p. 179):

Figure 1.1. Different Types of Portfolios

- Performance portfolios are collections of a student's best work, with the student taking the lead in the selection of the work and providing an explanation as to why they should be included.

- Process portfolios contain several versions of a selected work. Such a portfolio might hold early drafts of a paper or poem to show how the piece developed over time.

- Progress portfolios are often managed by teachers. They hold collections of work intended to illustrate children's development over time.

Bear in mind that regarding the different types of student portfolios, "few pure examples of any of these types exist" (Allington & Cunningham, 2006, p. 179). The vignette that follows is a good example. A teacher and a student celebrate a piece of published writing (a performance), yet it also serves as a point of instruction (progress). This combination of a showcase portfolio that is student driven and a benchmark portfolio that is teacher directed can be referred to as a "collaborative portfolio" (Jenkins, 1996).

In my experience, I have found it helpful when getting started with digital portfolios to categorize them based on purpose. We can refer to the three types of portfolios in terms of "best work" or "growth." Students, families, and colleagues typically understand this terminology better. Best-work portfolios are student driven and include collections of students' best work. Growth portfolios are teacher directed and represent students' development over time. Regardless of the type of portfolio, opportunities for documenting and sharing student learning can happen at any time. Teachers need to take advantage of these situations and worry about how to categorize them later, if at all.

To provide some context for digital portfolios, the following passage describes a small moment in which a teacher (Janice) is conferencing with a student (Calleigh). Janice video-recorded her writing conference using an application called FreshGrade. This conference was eventually shared with Calleigh's family through the application. Each piece selected by Calleigh throughout the school year is also saved within FreshGrade to show growth over time. Previously, Janice had provided instruction through minilessons on writing strategies. She was already aware of her students' writing abilities through a fall schoolwide writing assessment. The results of that assessment were quantitative (i.e., numerical) and based on one rubric. However, Janice's success in the writing conference was measured through Calleigh's ability to monitor her own growth in writing and take more responsibility for the results.

In the Classroom with Janice and Calleigh

Calleigh, a 2nd grader, sits down with her teacher, Janice Heyroth, to prepare for an assessment. This is a regularly scheduled conference during the middle of the school year; Janice meets with each student six times a year to reflect on a piece of writing in their digital portfolios. At the beginning of the year, students completed a reading and writing survey, which was uploaded and shared with students' families via FreshGrade. The information gleaned from that survey gave Janice information about each student's dispositions toward reading and writing. Questions such as "What types of books does your child enjoy reading on this/her own?" and "Does your child enjoy writing? Why or why not?" gave insights into how students approached literacy in their lives. It also informed her future instruction, such as generating writing ideas and topics students could choose to explore if they needed more support.

Elbows on the table, Calleigh props her head on her hands as her teacher spreads out some of her own writing. Because it is the middle of the school year, Calleigh's folder already contains multiple compositions. Janice encourages Calleigh to locate a recently published piece she is proud of. She selects one, and then Janice starts off their assessment with a question: "So, what are some things you are doing well?"

Calleigh doesn't hesitate. She states, "Handwriting." Calleigh pulls an older piece of writing from her folder and compares it with a more recent entry to show the difference. Janice listens and smiles while she writes down Calleigh's response in her conferring notebook.

Janice prompts, "What else?" and then silently waits and allows Calleigh the time she needs to look back at her writing and find other points to highlight. After a few seconds, she responds, "I don't know."

Janice acknowledges Calleigh's honesty and follows up with more specific language. She says, "Well, I have noticed a lot of areas where I think you're doing well in your writing. First, you stayed organized with your writing. Did you notice that?"

Calleigh tentatively nods.

Janice then says, "Do you know what I mean by staying organized in your writing?"

Calleigh hesitates and then smiles as she responds, "No."

"Okay … did you stay on topic?"

"Yeah"

"What is your topic about?"

"Going to Florida."

"Right. It's all about going to Florida. Did you tell me about what you did first and go all the way through to the end?"

"Yes."

The conversation continues, and while this assessment is taking place, the rest of the students in the classroom are busy independently reading and writing, working on self-guided vocabulary activities, or using computers to listen to narrated digital stories. At one point in the assessment, Janice starts to make a suggestion ("Would it have made sense …"), stops herself, and then restarts her inquiry: "Why did you start your real narrative in this way?" Calleigh shares that she started her story by describing an important scene during her visit to Florida. This is a strategy for developing a lead that she learned during whole-group writing instruction. Janice makes sure to note this connection between teaching and learning in her notebook.

The assessment closes with Janice asking Calleigh what she would like to continue working on with her writing. This time, she waits 15 seconds for a response.

Finally, Calleigh says, "Spaces."

Janice pauses and then responds, "Actually, your spacing is fine. The same with your spelling and handwriting—everything looks great. Let's take a look at your ending, though. 'Our trip to Florida was fun and exciting.' How could you have spiced things up and made your ending more memorable?"

Calleigh struggles with how to respond. Janice reminds her that endings can often resemble leads. With this information in hand, Janice makes a note to prepare future minilessons that address endings. Janice finishes up her time with Calleigh by showing her how to upload her writing to FreshGrade so her parents can see her work.

Assessment in Context

To understand how digital portfolio assessment can inform teaching and learning, let's unpack the conference scenario between Janice and Calleigh.

Relationships as a Foundation for Learning

Relationships are the cornerstone of all teaching and learning. Consider the initial interaction between Janice and her students. When Calleigh stated "I don't know" to Janice, she was being honest. She was willing to reveal her lack of knowledge about what good writing might resemble. Janice responded professionally, instead of "What do you mean you don't know? We covered this yesterday." She saw this admission as an opportunity for celebration and for instruction. Janice pointed out Calleigh's strengths in organization and how her conventions and presentation made her writing more readable. This opened the door for feedback and growth, especially when they started talking about her ending.

It is hard to learn from someone whom we do not respect or particularly care for. Learners must have trust in their teachers. Making mistakes puts us in a vulnerable position, and when we're forced to admit that we don't know something, we open ourselves up to potential criticism. This can be good situation if a high level of trust and a positive relationship have been developed between student and teacher. Students need to see their teachers as credible and reliable to be able to accept feedback about their performance.

Janice understood this. She maintained her relationship with Calleigh as a way to help her student grow as a writer. This trust was developed through genuine celebration and thoughtful interaction. In addition, it allowed Janice to document this assessment through a digital portfolio tool.

Assessment and Agency

As the writing conference transitioned from celebration to observation and feedback, Janice caught herself about to make a suggestion. This would not have been the end of the world, but it also would not have given Calleigh enough credit for her potential. By rephrasing her suggestion into a question, Janice allowed for Calleigh to take more ownership of her writing. Asking a question that begins, "Would it have made sense …" is leading and teacher directed. Unfortunately, this is much too typical in classrooms today. The alternative approach ("Why did you start your narrative …") casts the student in the position of expert and requires them to justify their decisions. Calleigh was asked to support her own writing decisions, which were the result of strategies previously taught in the classroom. Calleigh was the lead assessor in this situation, and Janice was acting as a coach looking to build independence with her student. Bringing an authentic audience into this conference heightened the importance of Calleigh's work.

Clear Criteria for Success

Near the end of the writing conference, it became clear to Janice that Calleigh lacked the knowledge to develop informed writing goals for the next time they met. At that point, she recognized the need to be more prescriptive in her feedback. Her suggestion was brief and built on prior knowledge (using leads to build endings), yet she didn't spend a lot of time on it. Using this gap in knowledge as information to drive her instruction, Janice began to plan a future minilesson (or two) on endings. Chances are high that if Calleigh, who happened to be one of the stronger 2nd grade writers, needed more instruction in this area, then so did her classmates.

It's hard for students to meet expectations in any discipline if the criteria for success are unclear. Assessment is effective when teachers can provide instruction during the process of learning. The function of the conference was for Calleigh to identify her best writing within the context of current work and the standards of excellence conveyed by Janice. Their conversation was about celebrating success and moving forward as a writer. Calleigh was therefore positioned to consider improvement instead of simply being evaluated. With this in mind, assessments should focus on teachers and students workin...