- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

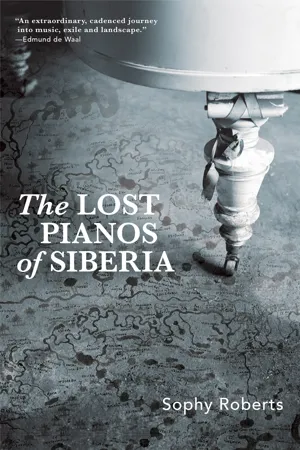

The Lost Pianos of Siberia

About this book

This "melodious" mix of music, history, and travelogue "reveals a story inextricably linked to the drama of Russia itself . . . These pages sing like a symphony." —

The Wall Street Journal

Siberia's story is traditionally one of exiles, penal colonies, and unmarked graves. Yet there is another tale to tell. Dotted throughout this remote land are pianos—grand instruments created during the boom years of the nineteenth century, as well as humble Soviet-made uprights that found their way into equally modest homes. They tell the story of how, ever since entering Russian culture under the westernizing influence of Catherine the Great, piano music has run through the country like blood.

How these pianos traveled into this snowbound wilderness in the first place is testament to noble acts of fortitude by governors, adventurers, and exiles. Siberian pianos have accomplished extraordinary feats, from the instrument that Maria Volkonsky, wife of an exiled Decembrist revolutionary, used to spread music east of the Urals, to those that brought reprieve to the Soviet Gulag. That these instruments might still exist in such a hostile landscape is remarkable. That they are still capable of making music in far-flung villages is nothing less than a miracle.

The Lost Pianos of Siberia follows Roberts on a three-year adventure as she tracks a number of instruments to find one whose history is definitively Siberian. Her journey reveals a desolate land inhabited by wild tigers and deeply shaped by its dark history, yet one that is also profoundly beautiful—and peppered with pianos.

"An elegant and nuanced journey through literature, through history, through music, murder and incarceration and revolution, through snow and ice and remoteness, to discover the human face of Siberia. I loved this book." —Paul Theroux

Siberia's story is traditionally one of exiles, penal colonies, and unmarked graves. Yet there is another tale to tell. Dotted throughout this remote land are pianos—grand instruments created during the boom years of the nineteenth century, as well as humble Soviet-made uprights that found their way into equally modest homes. They tell the story of how, ever since entering Russian culture under the westernizing influence of Catherine the Great, piano music has run through the country like blood.

How these pianos traveled into this snowbound wilderness in the first place is testament to noble acts of fortitude by governors, adventurers, and exiles. Siberian pianos have accomplished extraordinary feats, from the instrument that Maria Volkonsky, wife of an exiled Decembrist revolutionary, used to spread music east of the Urals, to those that brought reprieve to the Soviet Gulag. That these instruments might still exist in such a hostile landscape is remarkable. That they are still capable of making music in far-flung villages is nothing less than a miracle.

The Lost Pianos of Siberia follows Roberts on a three-year adventure as she tracks a number of instruments to find one whose history is definitively Siberian. Her journey reveals a desolate land inhabited by wild tigers and deeply shaped by its dark history, yet one that is also profoundly beautiful—and peppered with pianos.

"An elegant and nuanced journey through literature, through history, through music, murder and incarceration and revolution, through snow and ice and remoteness, to discover the human face of Siberia. I loved this book." —Paul Theroux

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Pianomania

1762–1917

‘Liszt. It is only noon. Where are those brilliant carriages travelling from every direction going with such speed at this unusual hour? Probably to some celebration? Not at all. But what is the reason for such haste? A very small notice, brief and simple. Here’s what it says. A virtuoso announces that on a certain day, at two o’clock, in the Hall of the Assembly of the Nobles, he will play on his piano, without the accompaniment of the orchestra, without the usual prestige of a concert . . . five or six pieces. Upon hearing this news, the entire city rushed. Look! An immense crowd gathers, people squeeze together, elbow each other and enter.’

– Journal de St-Pétersbourg, August 1842

1

Music in a Sleeping Land: Sibir

EARLY ON IN MY travels in Siberia, I was sent a photograph from a musician living in Kamchatka, a remote peninsula which juts out of the eastern edge of Russia into the fog of the North Pacific. In the photograph, volcanoes rise out of the flatness, the scoops and hollows dominated by an A-shaped cone. Ice loiters in pockets of the landscape. In the foreground stands an upright piano. The focus belongs to the music, which has attracted an audience of ten.

A young man wearing an American ice-hockey shirt crouches at the pianist’s feet. With his face turned from the camera, it is difficult to tell what he is thinking, if it is the pianist’s music he finds engaging or the strangeness of the location where the instrument has appeared. The young man listens as if he might belong to an intimate gathering around a drawing-room piano, a scene that pops up like a motif in Russia’s nineteenth-century literature, rather than a common upright marooned in a lava field in one of the world’s most savage landscapes. There is no supporting dialogue to the photograph, no thickening romance, as happens around the instruments in Leo Tolstoy’s epic novels. Nor is there any explanation about how or why the piano ended up here in the first place. The image has arrived with no mention of what is being played, which is music the picture can’t capture anyway. Yet all sorts of intonations fill the word ‘Siberia’ written in the subject line of the email.

Siberia. The word makes everything it touches vibrate at a different pitch. Early Arab traders called Siberia Ibis-Shibir, Sibir-i-Abir and Abir-i-Sabir. Modern etymology suggests its roots lie in the Tatar word sibir, meaning ‘the sleeping land’. Others contend that ‘Siberia’ is derived from the mythical mountain Sumbyr found in Siberian-Turkic folklore. Sumbyr, like ‘slumber’. Or Wissibur, like ‘whisper’, which was the name the Bavarian traveller Johann Schiltberger bestowed upon this enigmatic hole in fifteenth-century cartography. Whatever the word’s ancestry, the sound is right. ‘Siberia’ rolls off the tongue with a sibilant chill. It is a word full of poetry and alliterative suggestion. But by inferring sleep, the etymology also undersells Siberia’s scope, both real and imagined.

Siberia is far more significant than a place on the map: it is a feeling which sticks like a burr, a temperature, the sound of sleepy flakes falling on snowy pillows and the crunch of uneven footsteps coming from behind. Siberia is a wardrobe problem – too cold in winter, and too hot in summer – with wooden cabins and chimney stacks belching corpse-grey smoke into wide white skies. It is a melancholy, a cinematic romance dipped in limpid moonshine, unhurried train journeys, pipes wrapped in sackcloth, and a broken swing hanging from a squeaky chain. You can hear Siberia in the big, soft chords in Russian music that evoke the hush of silver birch trees and the billowing winter snows.

Covering an eleventh of the world’s landmass, Siberia is bordered by the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Mongolian steppe in the south. The Urals mark Siberia’s western edge, and the Pacific its eastern rim. It is the ultimate land beyond ‘The Rock’, as the Urals used to be described, an unwritten register of the missing and the uprooted, an almost-country perceived to be so far from Moscow that when some kind of falling star destroyed a patch of forest twice the size of the Russian capital in the famed ‘Tunguska Event’ of 1908, no one bothered to investigate for twenty years. Before air travel reduced distances, Siberia was too remote for anyone to go and look.

In the seventeenth century, wilderness was therefore ideal for banishing criminals and dissidents when the Tsars first transformed Siberia into the most feared penal colony on Earth. Some exiles had their nostrils split to mark them as outcasts. Others had their tongues removed. One half of their head was shaved to reveal smooth, blue-tinged skin. Among them were ordinary, innocent people labelled ‘convicts’ on the European side of the Urals, and ‘unfortunates’ in Siberia. Hence the habit among fellow exiles of leaving free bread on windowsills to help bedraggled newcomers. Empathy, it seems, has been seared into the Siberian psyche from the start, with these small acts of kindness the difference between life and death in an unimaginably vast realm. Siberia’s size also stands as testimony to our human capacity for indifference. We find it difficult to identify with places that are too far removed. That’s what happens with boundless scale. The effects are dizzying until it is hard to tell truth from fact, whether Siberia is a nightmare or a myth full of impenetrable forests and limitless plains, its murderous proportions strung with groaning oil derricks and sagging wires. Siberia is all these things, and more as well.

It is a modern economic miracle, with natural oil and gas reserves driving powerful shifts in the geopolitics of North Asia and the Arctic Ocean. It is the taste of wild strawberries sweet as sugar cubes, and tiny pine cones stewed in jam. It is home-made pike-and-mushroom pie, clean air and pure nature, the stinging slap of waves on Lake Baikal, and winter light spangled with powdered ice. It is land layered with a rich history of indigenous culture where a kind of magical belief-system still prevails. Despite widespread ecological destruction, including ‘black snow’ from coal mining, toxic lakes, and forest fires contributing to smoke clouds bigger than the EU, Siberia’s abundant nature still persuades you to believe in all sorts of mysteries carved into its petroglyphs and caves. But Siberia’s deep history also makes you realize how short our human story is, given the landscape’s raw tectonic scale.

In Siberia’s centre, a geographical fault, the Baikal Rift Zone, runs vertically through Russia to the Arctic Ocean. Every year the shores around Lake Baikal – the deepest lake on Earth, holding a fifth of the world’s fresh water – move another two centimetres apart, the lake holding the kinetic energy of an immense living landscape about to split. It is a crouched violence, a gathering strain, a power that sits just beneath the visible. The black iris of Russia’s ‘Sacred Sea’ is opening up, the rift so significant that when this eye of water blinks sometime in the far future, Baikal could mark the line where the Eurasian landmass splits in two: Europe on one side, Asia on the other, in one final cataclysmic divorce. Above all, Baikal’s magnificence reasserts the vulnerability of man. Beneath the lake’s quilt of snow in winter lies a mosaic of icy sheets, each fractured vein serving as a reminder that the lake’s surface might give way at any moment. Fissures in the ice look like the surface of a shattered mirror. Other cracks penetrate more deeply, like diamond necklaces suspended in the watery blues. The ice tricks you with its fixity when in fact Baikal can be deadly. Just look at how it devours the drowned. In Baikal there is a little omnivorous crustacean smaller than a grain of rice, with a staggering appetite. These greedy creatures are the reason why Baikal’s water is so clear: they filter the top fifty metres of the lake up to three times a year – another strange endemic aberration like Baikal’s bug-eyed nerpa seals, shaped like rugby balls, whose predecessors got trapped in the lake some two million years ago when the continental plates made their last big shift. Either that or the nerpa are an evolution of ringed seal that swam down from the Arctic into Siberia’s river systems and got stuck – like so much else in Siberia, unable to return to their homeland, re-learning how to survive.

Because Siberia isn’t sleeping. Its resources are under immense pressure from a ravenous economy. Climate change is also hitting Siberia hard. In the Far North, the permafrost is melting. More than half of Russia balances on this unstable layer of frozen ground, Siberia’s mutability revealed in cracks that slice through forlorn buildings, and giant plugs of tundra collapsing without a grunt of warning. Bubbles formed of methane explode then fall in like soufflés. But no one much notices – including Russians who have never visited, whose quality of life owes a debt to Siberia’s wealth – because even with modern air travel there are Siberians living in towns who still refer to European Russia as ‘the mainland’. They might as well be marooned on islands. Take Kolyma in Russia’s remote north-east, flanking an icy cul de sac of water called the Sea of Okhotsk. This chilling territory, where some of the worst of the twentieth-century forced-labour camps, or Gulags, were located, used to be almost impossible to access except by air or boat. Even today, the twelve hundred miles of highway linking Kolyma to Yakutsk, which is among the coldest cities on Earth, are often impassable. In his unflinching record of what occurred in the camps, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s choice of words – The Gulag Archipelago – is therefore rooted in fact, even if the phrase carries an immense metaphorical weight.

The Soviet Gulag – scattered throughout Russia, not just Siberia – was different from the Tsarist penal exile system which came before the 1917 Revolution, although the two are often confused. The Tsars could banish people to permanent settlement in Siberia, as well as condemn them to hard labour. Under the Soviets, the emphasis was on hard-labour camps only, wound together with curious methods of ‘cultural education’. Once your sentence was up (assuming you survived it), you could usually return home, though there were exceptions. Both systems had a great deal of brutality in common, with the Tsarist exile system turning Siberia into a prodigious breeding ground for revolutionary thought. Trotsky, Lenin, Stalin – they all spent time in Siberia as political exiles before the Revolution. So did some of Russia’s greatest writers, including Fyodor Dostoevsky, who in the mid-nineteenth century described convicts chained to the prison wall, unable to move more than a couple of metres for up to ten years. ‘Here was our own peculiar world, unlike anything else at all,’ he wrote – ‘a house of the living dead.’

Yet under winter’s spell, stories about the state’s history of repression slip away. Siberia’s summer bogs are turned into frosted doilies and pine needles into ruffs of Flemish lace. The snow dusts and coats the ground, swirling into mist whenever the surface is caught by wind, concealing the bones of not only Russians but also Italians, French, Spaniards, Poles, Swedes and many more besides who perished in this place of exile, their graves unmarked. In Siberia, everything feels ambiguous, even darkly ironic, given the words used to describe its extremes. Among nineteenth-century prisoners, shackles were called ‘music’, presumably from the jingle of the exiles’ chains. In Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, to ‘play the piano’ meant having your fingerprints taken when you first arrived in camp.

But there is also another story to Siberia. Dotted throughout this land are pianos, like the humble, Soviet-made upright in the photograph of a Kamchatka lava field, and a few modern imported instruments. There is an abundance of beautiful grand pianos in a bitterly cold town called Mirny – a fifties Soviet settlement enriched by the largest open-cast diamond mine in the world – and more than fifty Steinway pianos in a school for gifted children in Khanty-Mansiysk at the heart of Western Siberia’s oil fields. Such extravagances, however, are few and far between. What is more remarkable are the pianos dating from the boom years of the Empire’s nineteenth-century pianomania. Lost symbols of Western culture in an Asiatic realm, these instruments arrived in Siberia carrying the me...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map of Russia

- Author’s Note

- Part One: Pianomania · 1762–1917

- Part Two: Broken Chords · 1917–1991

- Part Three: Goodness Knows Where · 1992–Present Day

- Epilogue

- A Brief Historical Chronology

- Selected Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Picture Acknowledgements

- Source Notes

- Index

- About the Author