![]()

Part I

A Background of Inaction and Complexity

![]()

1

The Need for a New Model of Educational Leadership

Introduction

The first draft of this chapter was written in early spring 2020, when life across the globe was undergoing extraordinary changes. Areas of China and European countries like Italy, Spain and France were in complete lockdown. The UK was starting to enter the same situation, whilst North America, Russia, the Indian subcontinent, South America and Africa still had to experience this threat. Many governments affected by Covid-19 began ordering their citizens to self-isolate for weeks and sometimes months at a time, either because they displayed coronavirus symptoms or simply to stop them from catching and spreading it. Covid-19 didn’t seem to have the virulence of the Spanish flu of 1918–19 (Spinney, 2017), but it seemed at least as infectious, and with a mortality rate of somewhere between 1 and 5 per cent, and much higher for the elderly, and those with underlying medical conditions it needed to be taken extraordinarily seriously, even if tragically for many, it wasn’t. Now, two years on, most countries have felt its effects, many have gone through a number of waves of the disease, and new variants have added to global anxieties. Even as vaccines have come on stream, conspiracy theories about the non-existence of the virus, and of the supposed hidden intentions behind vaccine provision, have all added to the confusion, concern and uncertainty.

Yet in the years before the outbreak, warnings by epidemiologists about the development of similar diseases were ignored or downplayed in many countries, as either preparations were made for an influenza epidemic or other issues distracted politicians’ attention (e.g. Guardian, 22/10/20). Yet concerns over some kind of outbreak were very real and for extremely good reasons. First has been the extraordinary rise in the global population over the last century, from one billion to nearly eight billion, which has increased people’s proximity to one another, so facilitating the disease’s transmission. Second, the globalization of trade has meant that businesses have become producers of individual parts of consumables like cars and televisions, which are then assembled elsewhere, and so more travel and greater connectivity have increased. Finally, as more exotic holiday destinations have become possible, so the globalization of leisure has promoted diseases from being parochial to becoming, like their human hosts, international travellers. The spread of Covid has then largely been an effect of globalization, even if a covert one.

The effects of globalization upon educational leadership are reasonably similar, even if educational leaders have given them much less attention. This is perhaps unsurprising: many school leaders began as class teachers focused on student care and instruction, and a great many still experience an ethical compulsion to make a difference to their students’ prospects (Bottery, et al. 2018). So when Covid-19 arrived, Thornton(2021) suggested that educational leaders’ responses were going through three different phases – an immediate crisis phase, a phase of adaptation and a final ‘opportunity’ phase. In the UK, the picture was one which Beauchamp et al. (2021) described as headteachers spending much time providing clear information and communication to teachers, parents and students on a variety of change and response issues. These included things like the best strategies for avoiding the disease, understanding the latest and often confused and contradictory government directives and working out how best to apply these to their institutions and its members. They also needed to work out how to accommodate socially distanced students, teachers and other school employees. In addition, there were interesting affective and strategic responses. Beauchamp et al. (2021) then also describe the perceived need by many headteachers to develop greater personal resilience, and to develop flatter and more distributed forms of management and leadership, with greater levels of care, trust and staff collaboration. In similar manner, Thornton (2020) in New Zealand also described how secondary principals quickly prioritized individual well-being over learning issues.

Now if Thornton’s three-phase model is correct the leadership role will probably continue to change. Immediate responses followed by periods of adaptation are then likely to be followed by reflection upon longer-term changes. Such movement has also been seen more broadly, as new Covid variants have produced a number of different second and third waves, and there has been much societal concern that new vaccines might need creating if variants of Covid-19 become more resistant than earlier versions. If populations then did gain greater immunity, some thought that the disease might come to resemble influenza – as potentially life-threatening to the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions and as requiring a vaccine variant probably every year. Such adaptations, however, are still largely second-phase responses and perhaps the most important question long term is how any third ‘opportunity’ phase will be used, both societally and educationally. At this moment in time, such developments are still largely speculation, but it seems quite possible that this third phase may only be seen as the opportunity to relaunch the economy or to stockpile more vaccines, and then attempt to return to the previously existing state of affairs, with the educational leadership role reflecting the same very limited degree of change.

However, this would be a seriously wasted opportunity, as Covid-19 is not the only crisis to which societies and its educational institutions will have to respond in the next few years. Globally, many people are having to adapt to environmental conditions which were previously thought as ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ events but which are occurring on a much more regular basis. Global increases in the regularity and severity of storms have led to the flooding of homes and properties, mudslides and the stripping of topsoil from agricultural lands; higher temperatures are also leading to more regular episodes of drought, wildfires and creeping desertification (Wallace-Wells, 2019). Such events not only decrease food production but also pose serious health risks for many people, particularly the elderly, as well as threatening the extinction of many land-based and aquatic species. There is also increasing concern that pandemics caused by other zoonotic diseases – those which can jump from one species to another – may swamp health systems and then threaten a society’s very foundations. If such events were to occur, the educational leadership role would need to expand beyond such traditional duties as staff management, curriculum development, financial administration and policy implementation, and their role in a crisis would need to transcend that of low-level communicators of government instructions, managers of institutional social distancing measures, organizers of online teaching and of school closures and their reopening.

The need for educational leaders as macro-level stewards

In such circumstances there are a number of ways in which the role of an educational leader may need to change. If pandemics, local flooding or heat waves become more frequent, their role will likely need to evolve into one of developing a better understanding of such events before they recur and also of helping communities, parents and students to respond in ways appropriate to the local context. Some of this is already implicit in the role, as educational leaders are – by definition – stewards of their students’ welfare. So in better understanding damaging events and their causes, and in helping to inform and better prepare both present and future populations in their schools and communities for the emergence of such threats, their stewardship role will need to expand.

Such a notion of stewardship – in not only taking on but also educating others into a stewardship role – whilst currently not a central function, has certainly been discussed in the business and educational leadership literature. Hernandez (2008, p. 121), for example, talks of stewardship as ‘an outcome of leadership behaviour that promotes a sense of personal responsibility in followers for the long-term well-being of the organisation and society’. Similarly, April (2013) talks of the need for a form of leadership which ‘focuses on others, the community and society at large, rather than the self’. This is an idea which links well with the kind of magnanimous leadership which Aristotle (1976) talked about in leaders working for the good of others, whilst Sergiovanni (1996) and Greenleaf (1997) have both advocated a stewardship element in their discussions of servant leadership, in which the leadership role is viewed as serving the needs of members not only of their own institution but of their community as well.

Such writers then take the concerns of a ‘steward’ leadership beyond that of leading others in institutions and develop it into one which urges others not only to contribute to the betterment of their fellow members but also to consider how they can help towards the care of their community and the wider society. This is the start of a much-needed movement from focusing almost completely upon micro- and meso-concerns to considering larger macro-issues. This resonates with the kind of thinking by Singer (1981), who argued that human beings need to expand the area of moral and ethical concern beyond the purely human to embrace concern for the natural environment and all those, human and non-human, who share it. This then leads to a broader, more important, stewardship role, which is reframed to more greatly emphasize broader issues of sustainability.

Now there has been some coverage in the educational leadership literature on the subject of leadership sustainability. However, this has tended to focus upon the kinds of threats which globally have reduced the number of individuals applying for leadership posts and of leaving or retiring early because of stress and ill-health (Davies, 2007; Hargreaves and Fink, 2007; Doyle and Locke 2014). This literature then largely discusses the micro- and meso-level effects on leadership sustainability and borrows heavily from macro-level concepts about environmental sustainability, even if it does not make global ecological concerns a focus for the kinds of sustainability which leaders need to help develop. The omission of such ecological sustainability in leadership literature looks to be really quite dangerous, for despite a decades-long emphasis by most governments on economic prosperity, the real bedrock of societal sustainability, and therefore of educational and leadership viability, lies in the sustainability of the complex relationships of life on this planet (Dasgupta, 2021). If these are destroyed, then human societies and their economic policies also become unsustainable. Given such pivotal importance, failing to extend the stewardship role to embrace such concerns might well come to be seen as an abnegation of leadership responsibility.

However, this book is not suggesting that educational leaders should have some kind of oversight role for global sustainability. There are many better-qualified macro-level experts to take on such a role. But it is being argued that in accepting an ethical commitment of care and well-being to others, this cannot be limited to focusing on only individual human sustainability nor just upon micro- and meso-level concerns. Educational leadership needs to expand its stewardship focus beyond the personal, interpersonal and institutional, in order to understand the threats generated at macro-levels to all species, not just human beings. Educational leaders then need to enable students not only to become more personally sustainable but also, as they reach maturity, to embrace a societal role with respect to such concerns and responsibilities.

Educational codes

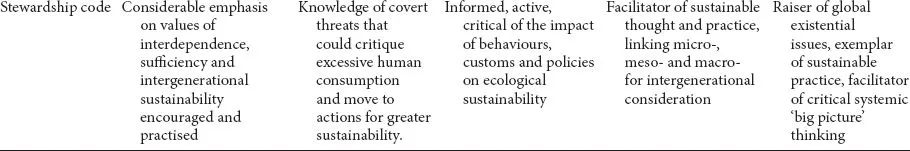

So how can educational leaders develop a stewardship role in their institutions? One strategy would be to review an institution’s ultimate educational purposes, content and values, and examine the extent to which stewardship concerns are included. Such ultimate purposes – such ‘educational codes’ – normally underpin the choice of curricula, pedagogy, the roles of teachers and educational leaders, and the kinds of citizenship felt most appropriate to that society. In previous writings, I have argued (Bottery, 1990, 1992) that four particular educational codes have normally been used in most societies. A first code – a cultural transmission code – is concerned with transmitting to students what are regarded as the best elements of a national and cultural past – the key events, issues and values. In so doing, students are then taught to embrace a selection (by others) of the content and values of their cultural heritage. Such content is often taught as matters of objective fact, even as it is a code which celebrates a particular version of the history of the past, steering students into celebrating this interpretation.

A second code, a child-centred code, has been employed when it has been believed that the interests and needs of the child should be paramount, and that their choices should dictate the selection of facts, issues and values. With a child-centred code, then, students are likely to be allowed to choose the topics they wish to study, students should be active in making sense of their learning and because maturity can only come about through the early exercise of responsibility and freedom, institutional management should reflect the importance of the student voice in more democratic institutions.

A third code, a social reconstruction code, has normally been employed when there is a perceived need for major societal changes. When this happens, particular issues are selected for discussion, and students are usually empowered into believing that they are capable of turning such discussion into action when they reach adulthood. This code would then very likely see as unacceptable any attempt to transmit bodies of knowledge established in a previous era which thwarted such empowerment. Educational institutions would instead be seen as a major way of changing society, where learning would be seen as a principal means of change. It would be an active process, guided but not dominated by teachers, who would help students to understand and critique materials, so that when older they could help to change social norms and institutions.

A fourth code, an economic code, is often promoted when the economic growth of a society and associated consumption and production are seen as paramount issues. Some of the important issues for this code in educational institutions are that schools should be important in furthering the economic prosperity of that nation, that they should produce a well-trained motivated workforce which not only competed in international markets but also provided students with the skills to earn a good living when they left school and that discussion, criticism and creativity should all be linked to the promotion of such economic goals.

Now whilst most educational systems incorporate emphases from all four of these codes, given the nature of many current and emerging threats, it is surprising how little they deal with the need for a greater environmental stewardship. Even the social reconstruction code, which emphasizes the need for greater social change, tends to focus more on problems within human societies than in dealing with external issues and forces which impact on a society. A stewardship code is then currently an outlier, even as there is now substantial need for it. Whilst, as already argued, a micro-level embrace of the concept of ‘stewardship’ is implicit in an educator’s role, a broader stewardship role must look beyond care and concern at personal and interpersonal levels, and make centre stage the adoption of stewardship attitudes of care and concern with respect to the ecological relationships on this planet, arguing that if the ecosphere is not sustainable, then neither is humanity. Finally, and to ensure that sustainability is inter- as well as intra-generational, it would need to embrace the view that the needs of present generations should not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

Each of these codes then is illustrated in Table 1.1, demonstrating different links between schooling and society, the type of knowledge valued and the roles allotted to students, teachers and school leaders.

Table 1.1 The Nature and Impact of Five Different Codes of Education

Such views are well rehearsed in the environmental literature, but there are a number of other issues in this broader ‘ecological’ vision of a stewardship code which have been much less emphasized in education systems and which are currently lacking in most educational leadership literature. The following six issues are then argued as being essential to an educational stewardship code.

The need for a more prominent macro-frame to the leadership role

The need for a more prominent macro-framing of the educational leadership role is partly addressed by a ‘critical’ educational literature (e.g. Rizvi and Lingard, 2009; Ball, 2012; Spring, 2014; Gunter, 2016), which argues that major global and national influences affect the purposes and manner in which educational institutions are run, and how the role of educational lead...