![]()

Fashion Victims

Men and women were expected to live very differently from one another, with clearly defined roles regardless of class. However, lift the skirts a little and not only will you see that they didn’t wear underwear (women were knickerless until 1800 when they started wearing ‘drawers’), they were far less repressed than the stereotypes would have us believe. The Victorians were as weird and wonderful as we are today.

It’s hard not to buy into the romanticism of Victorian fashion. Then, of course, one grows up and realises that those enormous gowns acted as an effective jail warden, keeping women in their place. Trussed up, squeezed tight and unable to perform basic human functions such as breathing, women could barely move, let alone find the energy for emancipation. Victorian women wore a tremendous amount of layers beneath their exquisite gowns: corsets, corset covers, petticoats, bloomers, bustles or crinolines, bust ruffles, garters and suspenders.

Read’s Crinoline Sketches, No. 9, 22 July 1859, by anonymous.

And, lest we forget, these fair princesses stank. Not just because of the general disregard at the time for regular bathing, but also after wading through the shit-covered streets with their delicate maiden feet.

Men fared little better. Confined to a strict dress code themselves, there was little space for freedom of thought – a gentleman was never seen in his shirt sleeves, and beards were in and out like a hokey-cokey. If you didn’t toe the sartorial line, you were regarded as a skilamalink (a man of shady character).

While men had misogynistic, unrealistic attitudes towards women, they too were subjected to rigid expectations. Women should exude a virginal, aesthetic grace while men had to be providers and moral guardians, and wear their success on the very shirt sleeves they needed to cover up.

The Victorian dress reform, also known as the Rational Dress Movement, proposed wearing clothes that were more practical and comfortable than the fashions at the time. Many women admired the strong heavy-set stability of Queen Victoria as much as they yearned to look like a frail wisp of a fainting damsel.

As we have seen, not all Victorians had a puritanical stick up their backside, and not all women wanted to be trussed up in acres of silk, unable to breathe. Underneath the stiff collars and the starched mountains of petticoats, there still lurked a naked animal with the same instincts as the rest of us. They had as many different ideas of beauty as anyone else, with many women lusting after brooding, immoral and wild Byronic heroes.

Still, all things are not created equal, and there’s a good reason why the dress reform movement mainly targeted female clothing. The story of women, as ever, is more complex than a frivolous and idiotic sex who sacrificed their health for their appearance. They were dressed in a beautifully embroidered prison. In a world where you were forced to base your future security on your partner and his approval, conformity was everything. Rebellious girls, who chose to deviate from the norm fashionwise, risked their marriage prospects – a fate that could land them in the workhouse.

This is not the book if you want to read a detailed description of all the Victorian styles and fripperies; many a detailed account exists that take you on a timeline catwalk. Far more titillating are the disasters, ironies and myths that followed this bountiful time of fashion, the often-ghoulish nature of Victorian dress and the far more frightening similarities to today.

These sexual politics dressed up in cotton and silk add another layer to the tale of Victorian beauty – a story that reads like a gothic tale straight out of a gruesome Penny Dreadful, complete with the horrors of fire-eating crinolines, arsenic-embroidered dresses and throat-puncturing collars that stalked nineteenth-century fashion.

Death was all the rage. From corpse chic to a string of people murdered by their threads, to the Queen’s unremitting grief for her husband that inspired a craze for mourning clothes: today’s goths would have killed (pun intended) to live in this era.

With short life expectancies, long mourning periods of at least a year were expected. (Side note: the upper classes changed their clothes about six times a day.) Following the death of her beloved Prince Albert in December 1861, Victoria dressed in black for the remaining forty years of her life.

Tuberculosis was so rife that it became an obsession for many Victorians and inspired a sickening, beauty trend. Women wanted to look like the victims of consumption. Popular writers, such as Alfred Tennyson, waxed lyrical about how a woman was at her most gorgeous when she was a corpse, as illustrated in this line from his poem Maud: ‘Pale with the golden beam of an eyelash dead on the cheek.’

A fair maiden’s highest compliment may well have been ‘Good God woman you look like death!’ It’s not a great leap to believe that men were responsible for this grisly look because no woman is as easy to control as a dead one.

The Victorian era witnessed ‘an increasing aestheticization of tuberculosis that becomes entwined with feminine beauty,’ says Carolyn Day, Assistant Professor of History at Furman University in South Carolina:

Among the upper class, one of the ways people judged a woman’s predisposition to tuberculosis was by her attractiveness. That’s because tuberculosis enhances those things that are already established as beautiful in women, such as the thinness and pale skin that result from weight loss and the lack of appetite caused by the disease.

So how did one replicate the nearly departed? Chalk-white skin was essential and lead-imbued cosmetics and arsenic helped achieve this look while hastening you to an early death. In a bizarre and grisly twist of irony, women were often forced to apply more and more lead makeup to cover the damage it had already wreaked.

Other ways to achieve the cute cadaver look was to paint thin blue lines to enhance the veins on white skin. And, of course, the thinner the better. The practice of extreme tightening of corsets was most helpful in restricting appetites and led to frequent fainting fits: mashing your lungs with reinforced whalebone had that effect.

As doctors searched for a cure, they recommended sunbathing as a treatment, which led to the popularity in tanning. (And disease, once again, informs our choices full circle as we go back into the shade to avoid skin cancer.)

Lola Montez was a famously scandalous courtesan and Spanish dancer who used her influence to demand reform (Victorian moralists loved her because she gave them so much to be indignant about), especially with regard to corsets. She said:

A display of Victorian-era cosmetics, including cold creams, hair restorer and various oils.

Above all things, to avoid, especially when young, the constant pressure of such hard substances as whalebone and steel; for, besides the destruction to beauty, they are liable to produce all the terrible consequences of abscesses and cancers. A young lady should be instructed that she is not to allow even her own hand to press it too roughly.

Portrait of Lola Montez by Southworth & Hawes, 1851.

Montez fascinated and appalled the Victorian community, but as a famous beauty, her advice was sought. Her book, The Arts of Beauty; Or, Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet published in 1858, featured a recipe for a breast growth serum:

Tincture of myrrh 1oz

Pimpernel water 4 oz

Elder-flower water 4 oz

Musk 1 gr

Rectified spirits of wine 6 oz

With the resulting tincture to be ‘very softly rubbed upon the bosom for five or ten minutes, two or three times a day.’

Montez summed up the cult of consumption most wittily by advising men to entertain their lady love by ‘relating the number of your female friends who have died of consumption within a year.’

Humour aside, she certainly bought into the zeitgeist of her day, saying: ‘Every woman owes it not only to herself, but to society to be as beautiful and charming as she possibly can.’

Certainly, your appearance was effectively your calling card. At a glance it told everyone who you were, how much money you had and how good your prospects were. Position was everything: women had to chase a good husband just to survive. They all knew the dangers of arsenic, belladonna and the like – these were common ingredients in a good old-fashioned Victorian murder – but they didn’t care. They were forced to place all their hopes on a decent marriage and if fair looks were created by foul means then so be it.

(Before Botox stops you raising your eyebrows in horror at your ancestors who were happy to drip deadly belladonna in their eyes to look ‘pretty’ – consider whether anything has changed. If you fast forward to history books in the twenty-second-century, they will have details of how women injected botulinum poison in their face and exploding sacks in their breasts.)

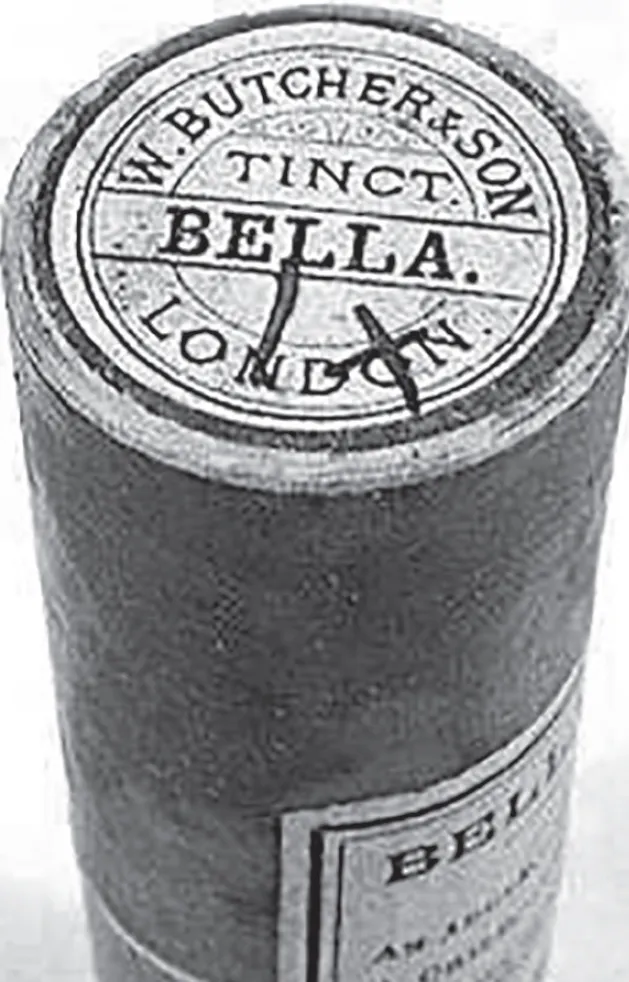

Belladonna was just one of several poisons that graced a Victorian’s beauty chest. It was used to create doe eyes by enlarging the pupil, creating a beautiful effect while causing blindness. Some women used lemon juice to achieve the same result.

Mrs S. D. Powers was the period’s most famous beauty expert, offering beauty solutions in The Ugly Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet (originally a column in Harper’s Bazaar). Some were less fatal than others.

Nibbling on Dr Rose’s white chalk arsenic wafers, sold by Sears and advertised as ‘perfectly harmless’, was believed to improve the complexion by slowly poisoning the woman, just enough to achieve the sought-after sick, pale and translucent look created by arsenic consumption, without actually causing her to collapse. The whiteness of the skin was also a clear sign that you were well-off enough not to have to labour like a commoner in the sun. Women would also ‘enamel’ themselves, coating their arms and faces with white paint and enamel to achieve the pale look. Wearing this meant a lady could not express herself facially in case the enamel cracked.

Glass bottle used for a tincture of belladonna, 1880–1900. (Science Museum Group Collection)

Unsurprisingly, Lola Montez despised the practice, saying, ‘If Satan has ever had any direct agency in inducing woman to spoil or deform her own beauty, it must have been in tempting her to use paints and enamelling.’

Mrs Powers advised ladies to use ammonia (also used to clean toilets) as the ...