![]()

1

Disturbed reciprocity: Rutherford Alcock’s diplomacy and merchant communities in China and Japan

Sano Mayuko

Introduction

Rutherford Alcock (1809–97) was one of the more prominent Western diplomats in nineteenth-century East Asia. He was appointed as Britain’s consul-general to Japan in 1858 – the year the post was created – and subsequently became Britain’s minister to Japan (1859–65)1 before being tapped for the same role in China (1865–71). Prior to assuming these high posts, he had been one of the first British consuls on the China coast, those officials charged with the administration of British affairs in the five treaty ports opened based on the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing: he had first been posted to Amoy in 1844, before being transferred to Fuzhou the following year.2 From 1846 to 1855, he had served as consul at Shanghai, where he acted as a major architect of the foreign concession system before being appointed the consul at Canton.3

His career in East Asia spanned twenty-seven years, twenty-three of which were on the frontline representing British interests (the other four years in total being periods on leave).4 Such an extensive career in one was rare at the time, when the climate in East Asia was especially severe and threatening to most Europeans, many of whom died or had to return home after serving for a short period of time because of sickness. Alcock was particularly proud of being an exception in this regard.5 His career, therefore, unusually reflects a long-term evolution of British activities in East Asia. Alcock’s stint in the field was still shorter than, for example, that of Harry Parkes (1828–85), who had lived in China during his childhood and who followed Alcock as Britain's chief diplomatic representative in Japan and China. Nonetheless, Alcock’s career is especially interesting to follow, as his every step was on the leading edge of the expansion of the British presence in East Asia.

It is, of course, impossible to retrace all of Alcock’s life in China and Japan in this chapter. I therefore must strictly limit my focus. In two distinct sections, I will zoom in on two windows in time, first on Alcock’s initial days in Japan in 1859,6 and a decade later – his final stint in China. I will explore how in both Japan and China, Alcock experienced heated confrontations with British merchants. His conduct on those occasions was based on a coherent thought process that would prove to be the chief distinction of his diplomacy. While drawing on previous studies, including my own, I will spotlight these confrontations and Alcock’s reactions recorded in his official dispatches and other writings. Although the facts depicted from the two periods are not entirely new findings, I break new ground by looking at both scenes in a single scope across the life path of Alcock, the individual.

This chapter aims to illuminate these experiences of Alcock, by which to see how they affected his career, as well as British relations with East Asia. Through considering these questions, I aim to explore possibilities for diplomatic history of these empirical studies that closely follow not only the larger diplomatic policy, but also an individual intimately involved in making that policy.

◊

Before examining Alcock’s experiences in Japan in 1859, it is worth looking at him, very briefly, about a decade earlier, when he served as the consul at Shanghai. In the course of his career in East Asia it was during his stint in Shanghai that Alcock became clearly aware of the presence of British merchants as an unignorable stakeholder in his official endeavours. His friction with British merchants is interesting because by definition, a ‘consul’ is supposed to take care of his/her fellow private citizens (largely merchants) and protect their interests in the area in which the consul is stationed. However, his former places of appointment – Amoy and Fuzhou – were literally new to Western trade and thus held no substantial community of merchants from Britain or any other Western countries. Therefore, in those posts, Alcock could concentrate on establishing his own presence, on behalf of his home government, vis-à-vis the local authorities.7 In this sense, his duties were on a single track.

In Shanghai, his life drastically changed. The city was already a flourishing port, with a British community of about ninety people,8 which sounds surprisingly small to us, but was fairly large in the context of the time. Upon the transfer of duties from his predecessor, George Balfour, Alcock became involved in a number of disputes concerning commercial activities, while also taking care of British residents as well as temporary visitors including the crews of British ships. He found himself, in the first place, as the head of the British community,9 which was completely different from the situation at his former posts. He struggled to adjust in this novel environment. Even in official documents, Alcock reveals his frustration of trying to respond fully to all demands from the British residents.10

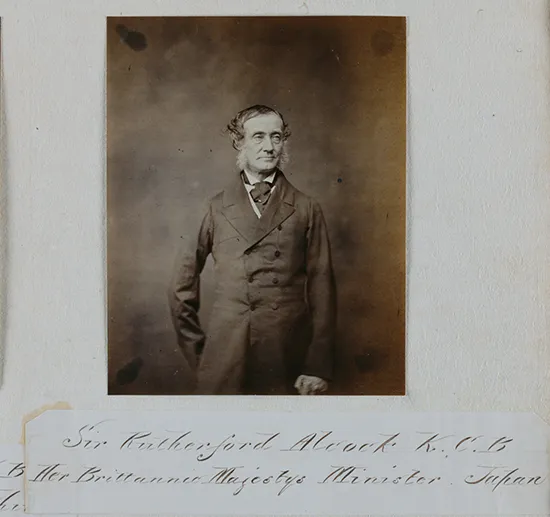

Figure 3 Felice Beato, Sir Rutherford Alcock K.C.B. Her Brittannic Majesty’s Minister in Japan. The photograph was probably taken sometime during his service in Japan from 1859 to 1865.

Image: Tokyo Photographic Art Museum /DNPartcom

The photo is owned by the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum.

These early experiences served as his on-the-job training, and through nine years of consulship at Shanghai, he became the founder of Shanghai’s well-known foreign settlement system as well as the Maritime Customs Service of China (initially introduced in 1854). In 1851 Alcock became interested in supporting Qing efforts to increase legal revenue from foreign trade by improving the custom system. Alcock viewed such efforts as a sound step forward within the Anglo-Chinese treaty framework.11 I will not further delve into this phase of Alcock’s life, but we should note that his support, which led to the Maritime Customs Service, was initially motivated by his frustration of seeing foreign merchants trying to evade customs duties. The British merchant community naturally disliked the new system, and many criticized Alcock for his role in implementing it. In response, Alcock declared he would gladly sacrifice his popularity among members of foreign community and not hesitate to take any criticism for operating in ‘good faith’ with China.12

The Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1858) permitted a British diplomat to reside in Japan and represent Britain in the newly opened country. The British Foreign Office transferred Alcock, its most experienced official in East Asia, from China to assume the new post.13

I. 1859 Edo/Yokohama

1) Alcock’s arrival in Japan and the ‘Yokohama question’

Alcock arrived in Japan in time to be present on 1 July 1859, the day stipulated in the Anglo-Japanese Treaty for the opening of Kanagawa, Nagasaki and Hakodate to Western-style free trade. He left the China coast at the end of May aboard HMS Sampson, which first called at Nagasaki, the nearest port from China, to leave three of Alcock’s colleagues to establish the consular service at that port (events explored in detail by Brian Burke-Gaffney in his chapter). He had a positive first impression of Japan based on his contacts with people in Nagasaki as well as the beautiful landscape of the city. Alcock thus appeared to have felt less dissatisfied about his new appointment ‘at the farthest limits of our intercourse with the Eastern race, instead of nearer home [in Europe]’. (He had earlier intimated that the posting to Japan did not sufficiently reward his long service in China.)14 On 26 June, HMS Sampson cast anchor in Edo Bay, off the coast of Shinagawa. Upon arriving in the shogun’s capital, the Briton was cheered by the unexpectedly prompt and pleasant reaction of officials from the Tokugawa shogunate. Alcock was especially delighted that Tokugawa officials soon offered to take him around the city to observe places designated as possible sites for the British legation.15

Contrary to the conventional understanding of Japan’s encounter with the West, the shogunate had been ready for Alcock’s arrival. Following the conclusion of the initial treaties of amity with the United States (1854) and Russia (1855) and the abandonment of the so-called ‘seclusion policy’, Tokugawa officials had been challenged by rapidly changing events in foreign affairs. The flurry of interactions with foreign states had honed their diplomatic practices.16 Moreover in 1858, they had also established a permanent institution in charge of foreign affairs (gaikoku bugyō) within the shogunate, instead of only temporary offices dealing with the visits of different foreign envoys.17

Accepting the Tokugawa offer, on 29 June, Alcock marked his initial step in Edo, becoming the first British representative (and the first from any Western country) to reside in the city. On the same day, he chose a large Buddhist temple, Tōzenji, for the British legation and his accommodation.18 He was fascinated by the beauty of the place.19

However, soon after, he faced a new difficulty, which I call the ‘Yokohama question’. While Yokohama, the port name, soon became famous, the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce (and US, Dutch, Russian and French versions, too) signed in the previous year clearly provided that the port of Kanagawa be opened to trade. Kanagawa was a busy post-town on the Tōkaidō, the most important trunk road of Japan at the time which connected Edo, the shogun’s capital, and Kyoto, the emperor’s capital. Moreover, as Kanagawa was very close to Edo (different from Nagasaki in the far west of the Japanese isles and Hakodate in the far north), it was supposed to be the core treaty port of Japan.

After signing the treaty, Tokugawa leaders began to worry about opening Kanagawa and accepting foreigners there; therefore, as a substitute, they quickly erected, before the designated date for opening the ports, a new town. Established on the site of a previously desolate village – Yokohama – not far from Kanagawa but opposite the bay from it, was conveniently isolated from existing Japanese business routes. The shogunate tried to direct the foreigners starting to arrive to trade to Yokohama instead of Kanagawa. Foreign representatives (Alcock and those from other nations who arrived subsequently20) were in the position to adhere to the treaty stipulations. They clearly objected to the arbitrary change of the port by Tokugawa officials. Nonetheless, merchants were attracted to Yokohama because the shogunate offered various advantages for residents and the site had the geographic potential to become a flourishing port. These merchants’ attitudes eventually nullified the diplomats’ protests to the shogunate.21

Traditionally, these circumstances have been attributed to the shogunate’s poor understanding of legal instruments. Namely Tokugawa officials surmised that the change of the port’s location was not a problem because Yokohama belonged to the broader vicinity of Kanagawa. They therefore could proceed as they desired.22 However, my research has shown that concerned Tokugawa officials were well aware they were breaching the treaty (and also that Kanagawa was not a name covering as broad an area as it does today).23 They knowingly chose to ignore the treaty in favour of their more urgent need to avoid allowing a foreign settlement to expand at Kanagawa. They therefore undertook enormous efforts to prepare Yokohama in advance of the foreigners’ arrival. To mitigate potential complaints from foreigners, they built in Yokohama a customs house, piers, other indispensable elements for trade, and even invited Japanese merchants to trade there.

It is also important to note that Alcock, when he visited Yokohama to observe the port for the first time on 1 July, perceived immediately the intention of Japanese officials.24 His report to the Foreign Office, drafted some days later, shows that he correctly divined the situation:

[T]he Japanese Government should have so far committed themselves to a line of policy it seems impossible for the Representatives of foreign Powers to endorse. The large expenses incurred have no doubt had this object in view – of making its final adoption inevitable. … The real motive of the Japanese, I have no doubt, from what has reached me, added to my own means of observation, is, first, to conciliate a powerful party among the most influential ‘Daimios’ or feudal Princes, by removing the foreigners from the line of their route to the capital in their frequent progress, in great state, to and from the Court of the Tycoon; and, secondly, to carry out, under specious pretexts, a policy which long habit has taught them to consider most consistent with their own interest and dignity, however prejudicial or fatal, under both aspects, to foreign States.25

Thus, he began to firmly protest the actions of Tokugawa officials, which he did not see as emerging from ignorance. He knew their intent and decided to fight.

There was one more element from which he learned the shrewdness of his Tokugawa counterparts. Alcock relays this in his 1863 book. He describes how shogunal officials initially tried to persuade him to accept Yokohama by untruthfully saying that the US consul-general, Townsend Harris, had already done so. Harris had arrived in Japan three years earlier, establishing a consulate in the remote village of Shimoda (in today’s Shizuoka Prefecture), a location stipulated in the US-Japan Treaty of Amity (1854). Harris had visited Edo a couple of times before he moved to reside permanently in the shogun’s capital, a provision made in the US-Japan Treaty of Friendship and Commerce (1858) that he himself signed as plenipotentiary.

Even if what he was told by the shogunate had been true, Alcock would not have had any idea to yield to it. Coincidentally, Harris joined Alcock in Yokohama on 1 July, on his way from Shimoda to Edo. He confirmed to Alcock that he had never accepted the opening of Yokohama instead of Kanagawa.26 The two men naturally decided that they should collaborate to battle with what they saw as Japan’s wrongful act. We can imagine, however, that what struck Alcock more severely was the fact that the Tokugawa side, if not successfully, intended to manipulate each of the foreign representatives, assuming the possibility that they might not necessarily share all information.

2) Alcock’s ‘First Lessons’

It is notable that Alcock gave the title ‘First Lessons in Japanese Diplomacy’ to the chapter reflecting this ‘Yokohama question’ in his 1863 book The Capital of the Tycoon: The Three Years’ Residence in Japan. This was literally the first problem in which Alcock became involved after arriving in Japan, which already resonates with the title. But what were the actual ‘lessons’ that he learned?

On the one hand, as I outlined above, it was no doubt about the shogunate, the government with which Alcock would have to deal. As a pioneer – the first resident representative sent to Japan which had been semi-closed to Western nations for centuries – he had been unable to possess any substantive knowledge about the actual character of Japan’s governmen...