The Model Black

How Black British Leaders Succeed in Organisations and Why It Matters

Barbara Banda

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Model Black

How Black British Leaders Succeed in Organisations and Why It Matters

Barbara Banda

About This Book

This book is for anyone who wants to understand what being more inclusive at work means, especially as it relates to black leaders. It is intended for those people who are saying "I don't know where to start, " "I don't know what to do" and "I don't know what to say" when understanding and talking about race at work. Based on candid interviews with 30 successful black leaders, it peels away the multifaceted layers of black British leaders in organisations to offer a new way of thinking about the black British experience.

This book provides the insights and ideas required to have positive conversations about race at work and to create work environments where black leaders can thrive. In identifying the attributes and behaviours that successful black leaders have in common, this book offers new ways of thinking about black people at work that help to further inclusion. It shines a light on the daily reality of being a black leader in the workplace, providing an alternative entry point for conversations around inclusion and explores what individuals and organisations can do to increase inclusion in the workplace. Through first-hand stories this book explores the challenges, compromises, struggles and successes that black people encounter, and the range of strategies they employ to achieve success as they navigate the "white" workplace.

It is essential reading for business leaders in the private, public and third sector, human resources professionals, students, anyone teaching or mentoring black students or leaders and everyone interested in understanding race and furthering inclusion in the workplace.

Frequently asked questions

Information

SECTION 1 HOW WE GOT HERE

1 "ANYWHERE EXCEPT THE MEAT COUNTER"

- discusses how black people learn, from their first employment, to navigate race at work;

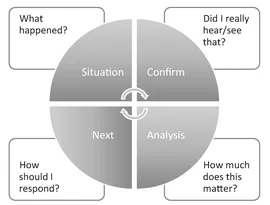

- explains how black leaders use the SCAN model to deal with race “in the moment”;

- explores the impact of a decade of reports on race in the workplace; and

- raises the challenge of talking about race at work – why do we still find it so difficult?

Everybody’s got a mother, or a father or brother or sister, and so on and so forth. I think the problem with race is that the other side of the line lies behind an opaque curtain. You literally don’t know what’s on the other side of that curtain – and by and large, how would you? Neither you nor I have ever been, by definition, in a circumstance where everybody in the room is white.Sir Trevor Phillips,OBE, Writer, Broadcaster and Former Head of the Commission for Racial Equality

People aren’t actively excluding people, not consciously necessarily, but the behaviours and what they expect of people, thus, by implication, they’re excluding people. So, this exclusion occurs often by accident . . . the majority of [white] people that you’d encounter that are professionals were actually good human beings who wanted to see people succeed.Michael Sherman, Chief Transformation and Strategy Officer, BT

You could just have a simple, zero-tolerance rule, that says, “Every time I experience racism of any type, I’m just going to go full-out and confront it.” Or you could have another simple rule which is like a lot of recent immigrants have done over the years, which is, “I’m going to keep my head down, and ignore it all. I’m just part of it. Grin and bear it.” There are two extreme rules. Neither of them, in my experience, work. In the middle, is me trying to figure out, on one day, I’m going to confront that . . . the way in which you respond – and this is the difficult part of the quiz show – the choices you make affect how people perceive you.Paul Cleal,OBE, Former Partner, PwC

It seemed like in the UK, no one even talked about race. The only thing that people successfully talked about in the boardroom or the executive meetings would be gender. We actually had what I consider progressive discussion around gender and gender equality. Gender is easier: Even broaching the subject of race was taboo which was quite shocking because, in America, it’s front and centre.Anon, Senior Executive, Technology

Everyone sees colour. You may not act on what you see, but you do see colour. It’s just like saying, “I don’t see sexual orientation,” or “I don’t see gender.” Those are all lies. Don’t perpetuate those lies and tell those lies to your colleagues because it just makes the mantra that makes it harder for your diverse colleagues.Anon, Senior Executive, Automotive

LEARNING TO NEED TO NAVIGATE RACE AT WORK

THE SCAN: HOW BLACK PEOPLE NAVIGATE RACE IN THE MOMENT