![]()

First Month of the Season of the River’s Flooding

THE FARMER

The blackness of a moonless night gave way to fading stars, and a slight and then growing tinge of grey. Alerted by the subtly growing light, a dozen species of birds contributed their voices to the anticipated grand phenomenon about to take place. As the grey gradually turned to a faint pink, the outlines of the surroundings gradually became visible: palms, acacias and the dark forms of mountains in the distance.

Baki lay on his side, awakening without prompt at an early hour as one who tends fields is accustomed. With a groan, he rolled over on his woven mat and accepted the fact that his sleep was over, at least for the moment. His two children were still curled up on the other side of the room but his wife, Mutui, had predictably arisen well before and her voice could be heard outside, softly singing as she began her usual daily chores. Grabbing a woven basket, she snatched handfuls of grain from the home’s ample granary, and knelt down before a polished rock slab. The rhythmic pounding and scraping of a smooth stone transforming wheat into flour was almost as comforting as the daily rising of the sun itself, bringing light and warmth every day, or at least one hopes it will continue to appear each morning.

With bleary eyes blinking in nervous anticipation, Baki arose to witness the unfolding celestial drama as he took his place on a brick bench in front of his simple home. Soon, he fervently prayed, a brilliant, glowing, warming orb would appear in full glory on the horizon, and begin its daily traverse of the sky. It was not to be taken for granted. Although Baki had rarely experienced a day that wasn’t at least partially sunny, he was well aware that if sufficient petition, appeasement and adoration weren’t consistently offered, the land he loved and thrived upon could be sunk into cold, darkness and death. Baki didn’t wait long, and he sighed with relief as the edge of the blazing glowing orb that is the god Re appeared on the horizon. Re, after disappearing into the west twelve hours previously, had died but had yet again successfully survived a night of defeating obstacles and perils in the Netherworld, to reappear triumphantly announcing a new day.

Re had never done otherwise, but that was only because he was sufficiently satisfied, at least in part by a large network of priests officiating in grandiose temples, ultimately presided over by the highest priest of all, Aakheperure Amenhotep, the ruler of the entire land. The priests must be doing their job well, surmised Baki. The sun god in his various forms continues to be appeased.

Re could be perceived in many variations. He could be seen as Re-Harakhty in the form of a great cosmic hawk whose wings slowly propelled the fiery disc across the daytime sky. Or one could view its propulsion as the result of a massive scarab beetle in the sky, who like the terrestrial version, which rolls a ball of egg-bearing dung before itself, pushes the great orange sphere towards the west. Or was it a great ship, plying the heavens with a contingency of gods aboard? And there was the Aten with its life-nurturing rays; but perhaps the strongest manifestation of all was Amun-Re, the sun embodied with the triumphant national god, the mighty yet unseen Amun.

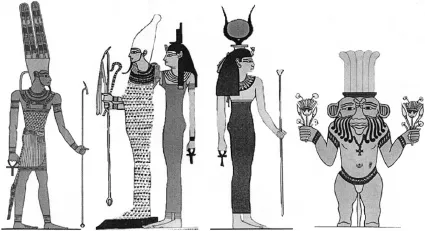

SOME OF THE EGYPTIAN DEITIES NOTED IN THIS BOOK (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT): AMUN-RE, OSIRIS AND ISIS, HATHOR AND BES

Amun was certainly overwhelmingly powerful these days. His temples were imposing, prolific and wealthy and his priests were numerous. Even the ruler’s name, Amenhotep – ‘Amun is satisfied’ – was a regular reminder of his greatness. Although Re and Amun were supreme, there were hundreds of other gods and goddesses, spirits and demons, who needed to be recognized and appeased or occasionally vanquished, representing all conceivable aspects of life and death. There was, for example, the goddess Hathor, who in the form of a cow could be a nurturing mother, but in the form of Sekhmet could be a fierce, bloodthirsty and protective lioness. On the kinder and more abstract spectrum was Thoth, who could be perceived as an ibis bird, and sometimes a baboon, and represented wisdom and writing.

There was Seth, who represented chaos, and Maat who represented stability. And then there were plenty of entities to be found in the life beyond, including Osiris, who ruled the Netherworld, a realm full of tricksters and malevolent creatures, and who presided over the judgement of the deceased. The sun god, Re, had to contend with the great snake, Apophis, who attempted to kill him every night. The gods could variably be depicted in human form, or as an associated animal, or with a human body and appropriate head. If one couldn’t read hieroglyphs, the head adornment on the statue or painting could help distinguish one from the other if they appeared similar.

Baki was a farmer, and despite the unrelenting woes of hard physical work, he genuinely loved his land. Gazing across a vast landscape of just-harvested fields, he was filled with deep appreciation of its beauty and abundance of produce. The fields lay along the banks of a magnificent river that wound its way from south to north to empty into the Great Green, a sea that Baki had only heard of (the Mediterranean). Believing that the flat earth was surrounded by waters above and waters below, ancient Egyptians imagined that the Nile percolated from a source below, somewhere far to the south.

THE NAMES OF EGYPT

The name ‘Egypt’ in English today seems to have its origins in the name of the temple of the god Ptah at Memphis, ‘Hut-ka-Ptah’ (House of the spirit of Ptah), which became Aigyptos in Greek, Aegyptus in Latin, L’Égypte in French, Ägypten in German, etc. In the modern country of Egypt today, the name in Arabic is Masr, its old origins suggesting a fortress or border. After the Greeks colonized Egypt beginning in the fourth century BC, many Egyptian towns acquired Greek names. ‘Waset’, for example, became ‘Thebes’, and ‘Men-nefer’ became ‘Memphis’. With the introduction of Arab culture in the seventh century AD, some sites also acquired new place names and ancient Waset/Thebes is today known as ‘Luxor’.

The river itself, the Nile, was a great wonder. In a normal year, its waters would rise and recede over a period of a few months, leaving the fields renewed with a rich black fertile muck that was perfect for growing essential crops such as wheat, barley and flax. As a result of this annual flooding and its fruitful outcome, Baki and his people called the land Kemet – the Black Land – referring to the rich fertility of the soil that allowed its people to flourish.

On very rare occasions, the river could flood too much and threaten villages situated on slightly higher ground, or perhaps worse, not rise much at all and cause famine. The great storehouses of surplus grain found throughout the land were a testament to the latter nagging possibility. The god Hapi, looking like a well-fed fellow with papyrus plants growing out of his head, represented the annual flood, and would hopefully remain more content than otherwise.

THE NILE RIVER

The ancient Egyptians referred to the Nile only as ‘the river’; it was the only river most knew. With its origins in the lakes of central Africa and the highlands of Ethiopia, it is the longest river in the world at over four thousand miles in length. The name ‘Nile’ has its origins in the Greek Neilos, meaning river valley. Several ancient civilizations, including Mesopotamia and Egypt, developed from agricultural societies established on the banks of rivers. In the case of Egypt, the Nile’s annual flood cycle which renewed the soil along its banks, provided an ideal environment for the Egyptian civilization to develop and flourish for millennia.

The river’s beneficial qualities weren’t confined to renewing the fields; its waters were teeming with many kinds of fish, and its shores were abundant with edible fowl and useful plants. It also served as a natural highway with its waters coursing north but its prevailing winds blowing south to fill the sails of those travelling in that direction. On most days, the river was alive with activity, with fishermen and others working along its banks, and ships of all sizes travelling in both directions.

Off to the east lay generally inhospitable deserts and mountains – the Red Land – and likewise to the west were wide expanses of unwelcoming territory, nearly waterless but spotted with a few oases. Exquisite stone and gold, however, could be quarried and mined in the east, and routes across this dry environment could take one to a great sea (the Red Sea) where maritime expeditions could be launched to exotic lands to the south. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of Kemet/Egypt’s millions of people lived directly along the river’s shores or on land between its tributaries, there being hundreds of villages and several large population centres.

Like most Egyptians, Baki couldn’t read, but had been taught by his elders who shared a general understanding of how his world had come about. There was once a time when there was nothing, but out of this void a god appeared, Atum, emerging from a primeval mound of slime, not unlike those that appeared on the fields as the waters of the annual flooding receded. Atum created a pair of gods, Shu and Tefnut, air and moisture, who in turn produced Nut and Geb, sky and land, all essential for the structure of the world and the maintenance of life. Four other gods were generated that were more human in nature: Osiris and his sister/wife Isis, along with Seth and Nephthys. (And there would be plenty of drama between them!) One of the gods, Khnum, would create humans and their spirits on a potter’s wheel and people would live and prosper along the river. Although all of this took place eons ago, the gods were very much still active, and of foremost importance in the continuation of society was the god Horus, the son of Osiris and Isis, who was embodied in the living ruler of Egypt.

Baki had also learned that long ago, there had been disputes between the people of the north – ‘Lower Egypt’ according to the downstream flow of the Nile, a place where the river splits into several multiple streams of the Nile Delta – and ‘Upper Egypt’, the relatively narrow and sinuous Nile Valley. More than a thousand years previously, a king of Upper Egypt remembered by the name Menes was successful in uniting the two regions and thereafter, the ruler of Egypt would be known as ‘Lord of the Two Lands’.

The capital – most commonly noted today by its Greek name, ‘Memphis’ – would be strategically established near the juncture of the two, both as an administrative centre for the vast bureaucracy that would emerge, and as a home for the ruler. Dozens of kings had ruled successfully over many centuries, and although Egypt had suffered at least two periods of disunity, it always recovered stronger in the aftermath. Egypt had now become so strong that it had reached far beyond its natural borders and controlled foreign lands to both the south and the east that could supply the homeland with great wealth.

EGYPTIAN NATIONALITY

Egypt’s xenophobic attitude was based not on race or skin-colour but on ethnicity. Unlike many cultures in the Near Eastern region, Egyptian civilization developed relatively isolated from others due to its geographical situation. Deserts to the east, west and south, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north provided natural boundaries and protection. Unpleasant and sometimes violent encounters with outsiders encouraged the Egyptians’ suspicions of foreigners. Outsiders could, however, become Egyptian, provided they fully adapted to, and participated in, Egyptian culture including its language, religion and authority.

Yes, Baki concluded, it was better to be an Egyptian than anything else. All who were not, he was taught, were inferior. To the south, beyond Egypt’s southern borders, were the typically uncooperative and surly inhabitants of Kush (Nubia). They had to be dealt with as their land was an irresistible source of exotic products including gold and other precious metals, as well as gems, gorgeous hardwoods, and even strange and curious animals. ‘Evil’ or ‘wretched’ were the terms often applied to Kush, and Egypt’s rulers took pride in subjugating them to build the wealth of Kemet.

Far to the east and north-east lived numerous people who were likewise considered lowly, and inhabited various towns and cities ripe for conquest. Military adventures in such places as Canaan and Syria were providing tremendous valuable resources including cheap labour by captives who could be assigned some of the most obnoxious of chores. And then, to the northwest, there were the Libyans, whose ways were similarly detestable.

Baki indeed felt lucky. He and his family lived in a village adjacent to the great city of Thebes, a religious capital in the south of Egypt and home to the ruler when he wasn’t in his palace in Memphis, or off visiting his realm. There seemed to be always something going on with boats coming and going, a plethora of goods being loaded and unloaded at the city’s ports, the comings and goings of Egyptian and foreign officials, and there were incredible temples to the gods, including Amun, the patron of Thebes and, realistically, all of Egypt. Amun’s temples in Thebes were almost beyond belief. It was impossible not to be awed by their stunning walls and statuary, and the soaring gold-gilded obelisks exploding with light when struck by the sun’s rays.

On the west side of the river, the impressive memorial temples of several previous rulers could be seen from the opposite shore, sacred places where priests assigned to the task still provided regular offerings. And speckling the nearby hills behind were a growing number of elaborate private tombs belonging to Egypt’s elite. Beyond lay a not-so-secret secret: a valley that served as a royal cemetery for Egypt’s rulers, the once-living god-kings who had shed their mortal responsibilities to spend a divine eternity elsewhere. It might be expected; after all, the west was the land of the dead, where Re descended, and jackals roamed the nocturnal landscape.

EGYPT’S PROVINCES

Egypt was traditionally divided into forty-two provinces, or nomes to use the Greek term commonly applied by modern scholars. Twenty were situated in the north, ‘Lower Egypt’, with the other twenty-two in southern ‘Upper Egypt’. Each had its own name, patron god, and accompanying temple, and was overseen by a governor (nomarch) who ultimately answered to the pharaoh and his administration. Egypt’s capital, Memphis, was within the first nome of Lower Egypt, the ‘White Walls’, with its primary god being Ptah. The vitally important city of Thebes was known as the Sceptre nome, where the god Amun reigned supreme. During times of political uncertainty in ancient Egyptian history, some of these nomarchs competed for power with varying results.

Baki returned to his bed and lay on his back, as the new light of day continued to fill the room. It seemed that every bone in his body ached from the previous days’ heavy efforts of harvesting what was left of the grain before the river would begin its slow rise and cover the fields. This day was, in fact, the beginning of a new year, the first day of the first of three seasons, and something worthy of celebration. For the moment, at least, Baki was content and looking forward to lighter chores and a bit of rest until the river would expectedly subside in a few months. Then the planting and harvesting would begin anew.

The New Year’s Festival

After b...